By Michael Streissguth

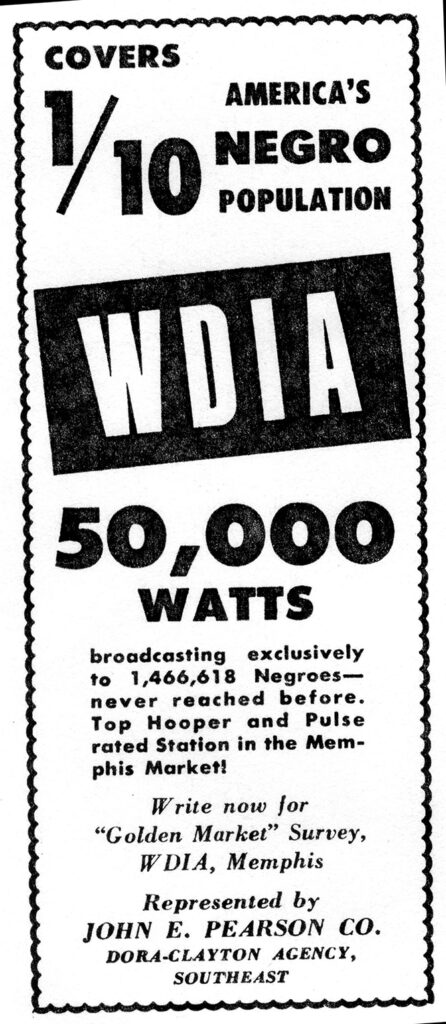

The violent backlash that program director Chris Spindel feared in 1948 when WDIA shifted to Black-oriented programming never materialized. Although, according to production manager Don Kern, hatred flowed fast and hard over the telephone lines: “They called up when we made the switch threatening to burn the place and shoot everybody and cuss everybody. It started out strong and then got stronger and then started fading. I’d say after a month there wasn’t much to it.”

The violent backlash that program director Chris Spindel feared in 1948 when WDIA shifted to Black-oriented programming never materialized. Although, according to production manager Don Kern, hatred flowed fast and hard over the telephone lines: “They called up when we made the switch threatening to burn the place and shoot everybody and cuss everybody. It started out strong and then got stronger and then started fading. I’d say after a month there wasn’t much to it.”

But Spindel’s fears only grew as the station more energetically courted the Black audience and on-air personalities began speaking out on racial justice: “I was nervous for Nat sometimes. He could be the target of something, like Medgar Evers. And he had this Brown America Speaks program and he didn’t mince any words and sometimes I’d turn it off. I just thought, ‘Nat, Nat, Nat. Slow down. There’s white people listening.’ But nobody ever bothered him, I don’t guess.”

But some whites around town protested in biting ways, as the station’s second Black hire, Maurice “Hot Rod” Hulbert, quickly learned. The WDIA sales manager took Hulbert to meet a white client who owned a furniture store, so the popular disc jockey could have a feel for the place when he plugged it on the air. But the owner wouldn’t shake the visitor’s hand. Hulbert wiped his hand and offered it again but the white man wouldn’t budge. “It was humiliating to me,” recalled Hulbert in 1989.

Inside WDIA’s offices, Spindel recalled just one employee who acted like the furniture store owner: “He was an announcer—I think he was from Illinois or Ohio—and he said he just couldn’t tolerate them. ‘I grew up with them. I went to school with them. But I just won’t work in a station where black people are going to be.’ It was strange. He was the one northerner and every southerner was for it. He left and went back up north.”

B.B. King often compared WDIA to his memory of the US Embassy when he played in Moscow in 1979. It was a refuge from uncertainty. “That’s the way we felt in Memphis until you got into WDIA. When you got there [people would say], ‘Hey, boy, what’s going on, man. . . . Hi, how’s everybody?’ And you felt free. WDIA did that and when problems was going on in various areas, WDIA was the first on the scene to talk about it. Man, I can’t tell you in words what it did for all of us. It made you feel like a whole person. You felt, ‘Hey, I’m part of something.’ You really felt good. From the management down it was like that.”

But to one of King’s white co-workers, the bluesman seemed ill at ease around the station. “If I walked into the room where we kept the records, he would never start a conversation,” said Ken Berryhill who worked at the station during summer breaks from school. “He would smile, but he would never speak unless I spoke first. He came up from Mississippi and coming to the big city and the situation between the blacks and the whites at that time. There was separation.”

Indeed, segregation in the Memphis of the late 1940s and early 1950s stubbornly traveled through the doors of WDIA. For example, only whites were permitted to be engineers, so Black personalities never cued up the records that they introduced or operated the control board. “Wasn’t nothing black there except the disc jockeys and the janitor,” said Gatemouth Moore. The preacher added that Blacks entered the station on Union Avenue through the back door, but Berryhill disputed that. In an interview, he said that the route from the back door would have tracked through Ferguson’s office, and, in his mind’s eye in later years, he could picture Nat D. Williams arriving at work through the front door.

The station’s policy that only engineers read hourly news updates barred Blacks from that job, too, since there were no Black engineers. But within a month of Williams’ debut on the station, the pioneering disc jockey had successfully lobbied for what he wrote was “the first Negro News-cast in the history of Memphis and the Mid-South.”

“It is my privilege to make this WDIA feature something I have long wanted to do,” he continued in his Memphis World column in late 1948. “I have had a long lasting yen to do something to give to the Negro-American some of that . . . favorable publicity and advertising which he has needed for so long.”

The as-yet untitled program that Williams envisioned probably became Brown America Speaks, which shone a light on issues of concern to Black listeners. However, hourly news updates would continue to be read by whites until the station hired its first Black engineer in 1954. All facets of WDIA’s staff would not be integrated until 1972 when the station finally hired a Black station manager. The station’s first Black owner was Ragan Henry, who purchased WDIA in 1983.