BUDDY GUY

BUDDY GUY

Ain’t Done with the Blues

RCA Records – No #

Buddy Guy is keeping a more active life since announcing his retirement from touring in 2024 than most of us working stiffs currently maintain. This year the 89 year old made a cameo in the hit film Sinners and he just celebrated his birthday by issuing the new double album Ain’t Done with the Blues. Recorded with his longtime collaborator and producer Tom Hambridge, the 18-track, 64-minute album crackles with vitality and some of the icon’s best songs and performances in more than a decade.

Ain’t Done with the Blues finds Guy touching on all aspects and influences of his legendary career. The autobiographical Been There Done That is a characteristically bombastic rocker. Guy looks back and recounts a life and career that often feels like something out of a novel or movie. “Been there and done that, still alive and well,” Guys sings, before punctuating that vigor with an electrifying solo.

If you’re into hearing Guy rip some hot leads and play some crunchy riffs, Blues Chase the Blues Away, I Got Sumpin’ For You, and Upside Down are sure to please. On It Keeps Me Young, Guy trades verses and licks with Peter Frampton to create a rough-and-tumble Chicago blues tune. Collaborations with Frampton, Joe Walsh on the scintillating How Blues Is That, and Joe Bonamassa on the reflective Dry Stick are highly effective, feeling more like organic pairings and less like buzzy guest spots. The gritty, fire-and-brimstone blues rocker Jesus Loves the Sinner, featuring the Blind Boys of Alabama, is one of the finest songs on the record.

Somehow, the Blind Boys track is merely the second best team-up on Ain’t Done with the Blues. The finest collab is Where U At. Featuring Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, some horns, and a punchy arrangement, it’s a slick slice of funk blues that allows Guy to sound spry while spotlighting the next generation of blues guitar heroes.

Guy bookends Ain’t Done with the Blues with a pair of acoustic tracks. Hooker Thing opens the record; it’s a nice tip of the polka dotted hat to Boogie Chillen by John Lee Hooker. He ends the entire affair with Talk to Your Daughter. A lively, rhythmic number, it makes for a fun conclusion to the album.

From start to finish, Guy shows that the title of this, his 20th studio record, is apt. He’s certainly not done with the blues. And we should all be thankful for that.

—Jim Shahen Jr.

LEONARD “LOWDOWN” BROWN

LEONARD “LOWDOWN” BROWN

Lowdown Street Party

Music Maker Foundation – MMCD224

Over the past few years, Leonard “Lowdown” Brown has emerged from his niche as a mainstay of the Houston blues scene to garner broader appreciation as a singer, songwriter, and guitarist. Since affiliating with the Music Maker Foundation, Brown has issued an acclaimed debut CD (Blues Is Calling Me, reviewed in LB #285), and also shared his story via a feature interview in this magazine (#290). Now, in light of his excellent new album of all-original material, those previous accomplishments might seem like a prelude. With its cohesive sequence of ten well-written songs and the production incorporating a superb cast of collaborators, Lowdown Street Party is indeed cause for celebration—the 72-year-old Brown’s best work thus far.

To make this album Brown created his own multi-tracked demos of the songs before traveling to Music Maker Studios, a new recording facility housed in a century-old building in Fountain, North Carolina. The versatile Jimbo Mathus—a prolific roots music artist perhaps best known as frontman for the original Squirrel Nut Zippers, as well as his collaborations with Buddy Guy, Alvin “Youngblood” Hart, and many others—serves there as house producer. He and Brown promptly hit it off, in part because, according to Mathus, “Leonard had it ready.” For the sessions, the producer played rhythm guitar and led a small but mighty unit of fellow accompanists, including a vocal trio known as the Crimestoppers. Given that first-rate supporting ensemble, Brown reciprocates with exquisitely expressive singing and meticulous guitarwork.

The opener immediately establishes that this production is something different in terms of both sound and concept. Simply titled Theme, it fuses an intoxicatingly rhythmic, congas-and-organ-accented funk with Brown’s nimble blues guitar licks and voice—all supplemented by powerful vocal punches from the backing chorus. Theme may be unusual but suits Brown’s implied vision for the album, which also loosely functions as a kind of autobiographical narrative. Rest assured, taken out of context, any one of these tracks can stand alone. The hard-driving Mojo Bag, for instance, with its ominous but mesmerizing vocal backing, evokes a universal blues trope. But as an interconnected sequence, they seem to cohere as one personal artistic statement.

For instance, the first couple of numbers, Theme and Street Party, ride a soul funk groove that recalls the popular sounds and carefree socializing of Brown’s youth in Gary, Indiana. Then the overarching story shifts to focus on interpersonal relationships and adult responsibilities, including a commitment to providing for his woman (I’m Gonna Take Care of You), as well as subsequent frustrations (I Need Help), and depressions (Don’t Wanna Get Up). One of the best tracks, highlighted by Brown’s delightfully nasty guitar licks, is the 12-bar romp Gotta Leave This Town, an ode to escaping a bad situation for something better. That thematic focus resurfaces in News with Blues, which summons a fabulous groove in counterpoint to lyrics about the psychic despair triggered by endless reports of societal ills and injustice. The penultimate track, a brightly loping shuffle titled Houston Bound, is the most overtly autobiographical as it references the economic downturn and industrial job layoffs that in 1981 prompted Brown to abandon Chicago for better employment in Texas. But it also alludes to the new musical identity that Brown—who up until then had performed only gospel and soul music—defined for himself as he assimilated into the Houston blues community. The set culminates with a celebratory number titled Big Blues Show, implicitly acknowledging the status the artist has now achieved as a respected contemporary player.

All in all, Lowdown Street Party is a highly satisfying recording. Drawing from his own life experiences, the veteran guitarist—who first performed on the gospel circuit as a teenaged instrumentalist—flourishes as a songwriter and singer. The savvy production, well served by all the accompanists, establishes a splendid sonic framework to showcase Brown’s multifaceted musicianship.

—Roger Wood

MUD MORGANFIELD

MUD MORGANFIELD

Deep Mud

Nola Blue – 047

Being the offspring of a musical legend is rarely easy—particularly if you decide to follow your parent’s professional path. And when the child sounds like, or even physically resembles, the parent, the expectations and comparisons are inevitable (as Julian Lennon would be the first to tell you).

And so it is—and has been—with Mud Morganfield, oldest son of Muddy Waters (McKinley Morganfield), since he first began performing the blues around his native Chicago a couple decades ago following his father’s 1983 passing. He woodshedded for about a quarter century before he ventured into the studio for his first album in 2008. But he has issued a half dozen more since then, on labels as respected as Delmark and Severn, leading us up to his most recent, on Nola Blue.

His similarity to his father in both tone and phrasing calls to mind Frank Sinatra Jr.’s embrace of his father’s canon and legacy. As with Sinatra Jr., there’s no sense of impersonating the father—rather, Mud simply inherited his father’s vocal cords and sinus cavities, and so can’t help but sound like Muddy. (The physical similarity, too, is striking—particularly around the mouth.)

As with most of his previous releases, Deep Mud shows that the son is a gifted composer all his own and not merely a nostalgia act. Twelve of the 14 tracks on the album are from Mud’s pen—the other two being from his father’s catalog. And his originals stack up against his dad’s just fine.

Bring Me My Whiskey kicks off the set in strong fashion—an up-tempo blues with Rick Kreher and Mike Wheeler’s dual guitars underpinning Morganfield’s rough and ready vocals, and producer “Studebaker” John Grimaldi’s harmonica darting in and out for emphasis.

The second track, Big Frame Woman, is another quick-paced blues—this one anchored by the piano of Sumito “Ariyo” Ariyoshi, while Morganfield’s soaring baritone describes his ideal mate.

The two Muddy covers deserve special consideration. Strange Woman finds Mud almost channeling his dad—the vocals are that close. The way he holds a note, the careful enunciation, the way Muddy clipped the end of a word, the shimmer in his delivery to emphasize a passage—it’s as impressive as it is moving. Country Boy, which Muddy recorded numerous times in arrangements ranging from simple acoustic guitar accompaniment to full band, is played with a quartet behind Mud—guitar (Kreher), harp, bass, and drums. And, as on Strange Woman, Mud’s vocal delivery is utter homage—although so is the arrangement and instrumental performances. Grimaldi’s harp sounds like classic James Cotton, and Kreher picks out slinky lines on guitar like he’s back in Muddy’s band again.

Most of the tracks here are of an old-school Chicago style—his father’s style, as the equally old-school Bill Dahl’s informative liner notes point out.

The exception is his original song In and Out of My Life, a slowly percolating R&B number. Ariyoshi’s stately piano undergirds Morganfield’s soulful vocals, which are framed by a classic female chorus. It’s not only a change of pace, but it shows a different side to Morganfield’s songwriting and singing, exhibiting a range outside his father’s considerable shadow.

That distinctive vocal style continues on the next track, The Man That You’re With. Not R&B, it’s a contemporary blues, but again finds Morganfield singing more like a soul singer than a traditional bluesman.

Most of us aren’t still charting new territory as we head into our 70s—but the stylistic stretches Morganfield exhibits here offer the promise of more interesting music still to come.

—Jim Trageser

ERIC GALES

ERIC GALES

A Tribute to LJK

Artone Label Group / Provogue Records – PRD77652

Blues rock firebrand Eric Gales has recently seen his career shift into high gear. His 2022 release, Crown, earned a Grammy nomination for Best Contemporary Blues Album, and his work on the soundtrack of Ryan Coogler’s acclaimed film Sinners has brought his music to a vast audience. On his latest release, Gales pays tribute to his late brother, Emmanuel Gales. A fan of Jimi Hendrix and a protégé of blues legend Albert King, Emmanuel Gales adopted the stage name Little Jimmy King. Before his untimely passing, Little Jimmy King perfected a style that mixed fretboard prowess with a deep grounding in blues and Memphis soul.

Opening track You Shouldn’t Have Left Me shows that Gales shares his brother’s gift for performing blues with a soul feel. Bassist MonoNeon and drummer Lemar Carter are in the pocket, while the five-piece horn section (arranged by Calvin Turner) fleshes out the sound. Salacious lyrics and high-powered musicianship turn up the thermostat on Rockin’ Horse Ride. MonoNeon and Carter slip into an airtight funk groove while Gerald Jenkins’ organ riffs stir some hot sauce into the mix. The intertwining guitars of Gales and guest Christone “Kingfish” Ingram are a joy to hear.

Something Inside of Me was the title track from a 1994 Little Jimmy King album. The lowdown slow blues is a great showcase for Gales’ expressive voice and expert guitar chops. While not averse to six-string pyrotechnics, he knows how to slow down and dig into a traditional 12-bar arrangement. Producer Joe Bonamassa lends his voice and formidable guitar skills to the swinging It Takes a Whole Lot of Money. Gales and Bonamassa have outstanding chemistry, and it’s a treat to hear them trade licks. Gales gives one of his most heartfelt performances on Worried Man, a tune penned by his late brother. His vocals are raw and vulnerable, and his guitar work includes some tasty Albert King– inspired deep bends.

Somebody, which features Gales holding his own next to Buddy Guy, is a beautiful way to close the album. A Tribute to LJK is both a moving tribute to a departed musician and testament to Gales’ substantial talent. He’s a force to be reckoned with.

—Jon Kleinman

ANNE HARRIS

ANNE HARRIS

I Feel It Once Again

Rugged Road – No #

Violinist Anne Harris has established herself through the years as a stylist, interpreter, and creative voice in multiple genres; these days, she’s known primarily for her work in blues and blues-related contexts. This, her latest release on her own Rugged Road imprint, finds her delving into a characteristically eclectic mélange of influences and styles, ranging from classically flavored folk pop (the opening Opus in E Minor) through updated variations on Celtic themes (Snowden’s Jig, I Believe in Being Ready) to layered, subtly electrified singer-songwriter introspection (the title tune; the socially charged Everybody Gotta Rise Up).

What this is not, however, is a blues album. Harris’ vocals, pristine and melodic, often multi-tracked and layered into sweetly yearning harmonies, eloquently complement her violin work, which—here, anyway—seems to reflect Anglo-Celtic tonal and harmonic influences rather than the harder-driving blues/R&B she has showcased when working with such artists as Billy Branch, Dave Herrero, and J.P. Soars (one critic actually described her as “one of the best rock lead guitarists in the US—even more impressive ’cause she’s playing the fiddle”). There’s an introspective yet uplifting sense of spirituality to this set—producer Colin Linden has created an aural landscape that’s both rich and sparse, with plenty of space for Harris’ music to evolve and grow on its own terms, conveying both urgency and tranquility—but a tranquility that demands vigilance, as Harris makes clear on Everybody Gotta Rise Up (“They want us scared of all the wrong things . . . They want us small, safe, and compliant / And they want it all, especially our silence / Everybody gotta rise up, rise up and shine”).

Frustratingly, no musicians’ credits are provided, so occasionally it’s difficult to tell whether some of the solo work is coming from Harris’ electrified violin or an uncredited guitarist (which may be why that critic made the comment he did). Also, a lyric sheet would have been helpful; Harris’ lyrics are heartfelt and eloquent, but at times her voice is mixed so low that some of the words get lost. Nonetheless, this is a deeply satisfying outing, allowing us an intimate and inspiring session with an artist whose commitment to musical excellence, social justice, and spiritual uplift makes hers an essential voice in our fraught times.

—David Whiteis

JOHNNIE JOHNSON

JOHNNIE JOHNSON

I’m Just Johnnie

Missouri Morning – 95269-37320

Stardom only came to the late Johnnie Johnson some decades after his influential piano playing behind Chuck Berry helped define the possibilities of rock ’n’ roll. But after his first album as leader, Blue Hand Johnnie, was released in 1988, he stayed busy with another half dozen albums either fronting his own band or co-leading with the Kentucky Headhunters before passing away in 2005.

While Johnnie Be Eighty and Still Bad! came out the year that he died, it wasn’t the last we’d hear from Johnson. The 2007 release, With Friends, featured Johnson in a series of duets with Keith Richards, John Lee Hooker, Albert King, Jimmy Rogers, among others. But given that Hooker, King, and Rogers had all preceded Johnson in passing, it’s not clear when that set was recorded—but at least some of the tracks would have had to been laid down in the 1990s unless it was just double-tracking Johnson’s vocals over existing recordings. Eight years after that release, Alligator issued another set with the Kentucky Headhunters that they’d had in the can since 2003, Meet Me in Bluesland.

Now we get the just-released I’m Just Johnnie, which producer Gene Ackmann says was laid down in the final months and weeks before Johnson’s 2005 death.

It’s not explained why it took 20 years to get this collection released, but it’s a fitting farewell—with guests ranging from Bonnie Raitt to Bruce Hornsby and John Sebastian to Johnny Rivers, who all came to St. Louis to record with Johnson according to the press notes. Rivers, a fellow veteran of the 1950s rock ’n’ roll vanguard, even brought two songs to the proceedings.

The highlight may be Broke the Bank, a tune composed by Johnson and Ackmann. It’s a straight-ahead blues shuffle. Johnson’s vocals are a little rough, although he stays in range. What catches the ear is at about the halfway point he lays down an extended bit of classic boogie-woogie piano before handing it off to Sebastian for a spirited solo on harmonica.

The instrumental romp Blues in G, with just a stripped-down quartet of Johnson, Tom Maloney on guitar, Gus Thornton on bass, and Kenny Rice on drums is another gem. Johnson takes the opening theme on piano for the first minute or so before Maloney leans into a jazz-infused improvisation, mixing narrative picking with harmonic strumming.

Hornsby and Johnson share both piano and lead vocals on an up-tempo cover of Every Day I Have the Blues. We don’t often get to hear one piano player comping behind another on lead, making this a nice treat. Raitt’s fills and punctuation on slide guitar add some spice as well.

The first of the Rivers-penned songs, Lo Down, features Henry Lawrence on vocals, with Rivers sitting in on guitar. It’s got a catchy theme draped over an R&B chassis, with a horn section framing both Lawrence’s earthy singing and Johnson’s bluesy piano.

Rivers’ other contribution, Johnnie Johnson Blues, is another quartet setting, but with Rivers replacing Maloney on guitar. It’s a slow blues, with Johnson singing his own life story, as told through Rivers’ lyrics. It is interesting to hear how Rivers’ hard rock style and sound on guitar still mesh an old-school composition and Johnson’s own approach on piano.

In a way, even though two more songs follow that track, it’s still a bookend to the opening song, the title track. Written by Johnson himself, I’m Just Johnnie is another autobiographical tale—this one in a rock ’n’ boogie vein. Tony T.’s guitar is quite similar to Rivers’ on the subsequent track.

Right up to the end of his time in this life, Johnson was a giant of the keys. The vocals are a bit uneven at times, but at no point does his piano playing ever flag.

The supporting cast is solid, the recording mix clean.

It’s hard to imagine that Johnson isn’t pleased with the end result.

—Jim Trageser

GINA COLEMAN

GINA COLEMAN

Unequivocally Blue

Guitar One – No #

On her own, leading a succession of groups, and in recent years fronting the Misty Blues Band, Gina Coleman has paid her dues and earned accolades while doing so. A two-time nominee for songwriting (in the Best Contemporary Blues category) by the Independent Blues Awards, Coleman is also an accomplished gospel and blues vocalist and cigar-box guitarist.

Coleman’s musical assets are on display on her new release, Unequivocally Blue. As the disc’s liner notes explain, the session for the album followed immediately—within an hour—of Coleman’s return from her mother’s funeral. That backstory provides helpful context for the album’s most emotionally rich moments.

The album opens with No More to Give, a lump-in-the-throat cris de coeur. It’s the only track on the album where Coleman accompanies herself on guitar; elsewhere on Unequivocally Blue she focuses solely on vocals, leaving the instrumentation to her capable Misty Blues Band mates.

Coleman’s voice is an instrument capable of a great deal of expression. While her husky, doleful approach on No More to Give is note-perfect, it’s merely one side of her artistry. Days Gone By almost sounds like a different singer; it’s comparatively upbeat and playful, with some tasty slide work from Seth Fleishman. The title track swings in a slinky manner, veering tantalizingly close to jazz; Coleman’s vocal moves in that direction as well.

Let Them Blues places acoustic guitar in the lead, with a set of bouncy standard blues changes underpinning the tune. It’s soul-inspiring in a secular sort of way. Ain’t No Giving Tree sounds like a different band on a different album, moving in an almost pop direction. Somehow, it works in the context of the album, underscoring the versatility and range of Coleman and her band.

Fly With Me is hypnotic and subtle, with a lively, understated instrumental break. The sassy How the Blues Feels is torchy and sensual. Up Above My Head is playfully funky, with a Staple Singers–inspired gospel feel. The spare Nothing’s in Vain is haunting, meditative, and moving. A deep groove forms the basis of Stoop Stomp; it’s a reminder yet again of Gina Coleman’s stylistic range.

The album concludes with an atmospheric track: Will My Blues serves up gentle guitar picking and pattering percussion, plus Coleman’s stirring voice. It’s blues in its lyrics, if not in its arrangement. And it’s an uplifting note upon which to end the record.

—Bill Kopp

The Definitive Albert White

Music Maker Foundation – Listeners Circle Vol. 69

Albert White, 82, became a mainstay of the Music Maker Blues Revue back in 1995, so 2025 marks his 30th anniversary on their team. Its executive director, Tim Duffy, says, “His voice and guitar get better year after year,” so when Music Maker Studios opened in Fountain, North Carolina, “The first artist I wanted to get in there,” Duffy remarked, “was our old trusted partner Albert.”

White is the nephew of Willie Lee “Piano Red” Perryman and was still in his teens when he joined Dr. Feelgood & the Interns. He spent several years on the road with Perryman and also fronted his own group, becoming popular at college gigs. White would later play sideman roles with such luminaries as Ray Charles, Hank Ballard, Clarence Carter, and others. His Music Maker Foundation bio rates him “a killer rhythm guitarist—and a great soloist when asked to be. He makes everyone around him sound good.”

White’s career as versatile sideman makes him someone who can sing and play music for all occasions: if he were of an earlier generation, might we call him a songster? That helps explain the 11 disparate covers that comprise The Definitive . . ., ranging from the early 1950s (Percy Mayfield’s River’s Invitation) to the early 1970s (Al Green’s Let’s Stay Together). It seems White, with years of stage experience, chose songs he knows go down well with audiences, even if in the aggregate they make for a slightly unfocused album.

The party begins with Let’s Go (a.k.a. Thrill on the Hill), a 1960 Hank Ballard romp that’s delivered con brio and, much like the original, complete with backup vocalists. That’s the most upbeat of the non-blues songs here. The others are ballads of sorts: the Impressions’ Gypsy Woman, the Tams’ Untie Me, Chuck Willis’ What Am I Living For?

Blues commences on the third track with a rendition of Little Mixed Up, the great Betty James song, and White opens his cover of Freddie King’s Tore Down with some hot licks before singing its bad feelin’ lyrics to an energized groove. The venerable Drivin’ Wheel is this album’s toughest track; White’s vocals here certainly belie his years. River’s Invitation offers some tasty slide guitar, and the album closes with a well-delivered blues ballad Breaking Up Somebody’s Home, variously associated with Ann Peebles and Albert King.

There’s much to like here, despite this reviewer’s hunch that sharper genre focus on the material might have resulted in a stronger album. There’s no info on who, other than White, plays here, which is a shame. But as a 30th anniversary salute to a gifted Music Maker who still delivers the goods handily at 82, this is a treat.

—Mark Humphrey

CANDICE IVORY

CANDICE IVORY

New Southern Vintage

Nola Blue Records – NB 045

Dynamic vocalist and performer Candice Ivory, the “Queen of Avant Soul,” shines bright on her new album, New Southern Vintage. This is an album that should be played loud and often, for Ivory’s emotionally drenched vocals deeply permeate our bodies and souls, driving us to get on our feet and move to these songs.

The down-and-dirty blues romp Ain’t So Blind launches the album with a propulsive ZZ Top–like rhythm; it’s a can’t-sit-still romp that sets the bar for the rest of the album. Snaking guitars lead the way on the shimmering Blue Blood, on which Mississippi Hill Country blues meets Memphis soul rhythms. Bright roadhouse piano and screaming slide set the scene for the swaying New Orleans stride blues I’m in Trouble. Barrelhouse piano lays the foundation on Lookin’ for My Baby, a hard-charging track that climbs higher and higher into the blues rock stratosphere; this rocker grabs us and won’t let go. Let Your Love Shine On features Ivory’s smoky and sultry vocals flowing over an echoing blend of psychedelic rock and soul. On the spare Corrina, Ivory’s vocals precisely match the piano notes that provide the musical foundation of the song; in her performance, she bares her soul, and the song overflows with emotion. Ivory’s vocals soar on her atmospheric version of Memphis Minnie’s World of Trouble, and the album closes with the jumping and jiving take on Memphis Minnie’s Shout the Boogie.

Every song on New Southern Vintage is a gem and showcases Candice Ivory’s deep love for the blues and her ability to dwell in the music and shape every song she sings. She’s a powerhouse singer who turns every performance into gold.

—Henry L. Carrigan Jr.

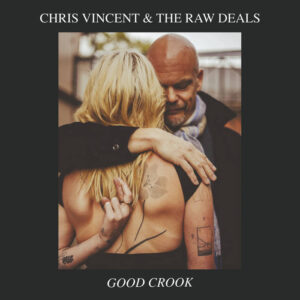

CHRIS VINCENT & THE RAW DEALS

CHRIS VINCENT & THE RAW DEALS

Good Crook

Chris Vincent Music – No #

Chris Vincent found the perfect milieu for his song/poems on the seedy side of New Orleans. On Good Crook, the guitarist and vocalist talks/sings a dozen original compositions that take a walk on the wild side through the edgy underbelly of the Crescent City. Vincent’s swaggering, gravel-road voice—melding equal parts Delta blues, Captain Beefheart, and Tom Waits—matches perfectly with the dramatic, brash accompaniment of his 1947 Gibson L-7 that he’s dubbed “Gloria” (as well as a 2019 Gibson prototype round-hole archtop). But what brings the lion’s share of these performance pieces alive is his recruitment of New Orleans stalwarts bassist Dean Zucchero and especially drum master Johnny Vidacovich.

The whole affair has a live-in-the-studio feel with Vincent plunging into his dramatic delivery of the words to rowdy guitar accompaniment with Vidacovich particularly enlivening the performances with his improvisational wizardry that always enhances the song’s story. The title track is a roiling boogie that opaquely looks at a bad romantic breakup boosted by a filthy guitar tone and bashing drum part. Midnight After All is a lumbering blues rock number with an unrelenting groove. Vincent channels both Son House and Keith Richards (particularly the Stones track Thru and Thru) with an open G tuning on Come Clean, the tale of another crumbling relationship. Vidacovich’s brushed cymbal and snare work bring a quiet fire to the poignant existential meditation of Skinned Knees. Vincent creates the persona of a man trying to carry on in the face of adversity on the boogieing Half Block Cadillac that features a loosey-goosey second line groove from the drummer.

The program also includes solo outings from Vincent, including the John Lee Hooker–evoking Snakes, the jazzy riffing on Cows, and the vagabond philosophizing of Bloody Mary Monday Morning. The day-long session in the studio with Vidacovich, who responded to the freewheeling spontaneity of the leader’s approach with the mantra “It’s all a movie, man,” inspired Vincent to write What Johnny Said, a commitment to change intoning, “It’s all a movie, man / It’s already been said / It’s all in your head / Shout from the rooftops / I’m coming home.” With Good Crook, Chris Vincent applies his unique vocal and guitar stylings to a set of compositions that present a persona struggling through a down-and-out cityscape yet driven to carry on despite it all.

—Robert H. Cataliotti