SELWYN BIRCHWOOD

Exorcist

Exorcist

Alligator Records – AL5012

Selwyn Birchwood cuts loose on his new record, Exorcist. The singer-songwriter-guitarist extraordinaire offers up 13 choice cuts that highlight his soulful vocals and incendiary lead guitarwork. His fretwork fireworks and powerful vocals are expertly produced by Tom Hambridge (Buddy Guy, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram), positioning Birchwood as a rising blues phenom worth following.

The bombastic lead single FLorida Man pokes fun at the lunatic “Florida Man” trope and, if one is so inclined to use it as such, could double as a form of ironic protest against at least one US presidential hopeful. FLorida Man is followed by arguably the finest track on Exorcist, Horns Below Her Halo. Birchwood’s vocals are sultry as he sings about a woman he’s enamored with, but what really stands out is his guitar playing. The song opens with a nasty solo. Then he offers up two more, including a blistering extended lead outro that wows.

The title track is a swampy blues-funk amalgam, like if Santana formed in the Sunshine State instead of the Golden City of San Francisco. It’s a bold song, serving as a way to showcase both Birchwood’s phenomenal guitar playing and ability to just uncork a tasty groove. The mostly instrumental Call Me What You Want To is another groover. It’s rooted in barroom blues, with Ed Krout playing a nifty solo on the Hammond organ and Birchwood playing a tasteful lead for two minutes before singing a short verse to bring the track to a close.

Exorcist comes to a close with Show Tune. It’s ebullient, big, and brassy, a bit of a companion piece to Call Me What You Want To. While the bulk of the album is built on impressive, squealing leads and Birchwood belting out his words, this track is the work of a band vamping and having fun. It makes for an elegant conclusion to an impressive album.

—Jim Shahen

BOO BOO DAVIS

Boo Boo Boogaloo

Boo Boo Boogaloo

Blue Lotus – BL-21

For the past two decades, the Drew, Mississippi–born Boo Boo Davis has showcased his harmonica playing and vocals on a string of records for Jan Mittendorp’s Netherlands-based Black & Tan Records, whose releases have, at times, mirrored Fat Possum’s treatment of R.L. Burnside material by remixing Davis with turntable scratching, overdub sampling, and hip-hop drums.

On Boo Boo Boogaloo—his inaugural release for independent label Blue Lotus in St. Louis, where Davis first made his mark after moving there in the early 1960s—Davis and company steer back to a more traditional production. St. Louis blues scene mainstays LA Jones (guitar) and Adrianna Marie (bass) anchor the band, along with drummer Chris Miller and keyboardist Paul Niehaus IV on deck. It’s a tight, seasoned outfit that knows how to back a harmonica player, giving Davis plenty of room to blow when he chooses, accompanying without overcrowding.

This is straightforward, meat and potato blues, with all ten tracks apparently cut on a single day in October 2022. Although primarily cast in the postwar style, no two songs are alike, and there’s enough rhythmic diversity here to keep the album moving briskly across its 50-minute run time. Standout tracks include the opening mid-tempo shuffle Little House by Myself, the slow blues I Got the Crying Blues, and the delightful soul ballad Make Everything Alright, a highlight thanks to Davis’ surprisingly tender vocal performance.

Readers in the St. Louis area can catch Davis live (often with Jones and Marie) at local clubs there, and he’s booked as a featured performer in this year’s Eastside Kings Festival in Austin (September 9 and 10). For everyone else, Boo Boo Boogaloo is a fine way to enjoy the talents of this 79-year-old bluesman.

—Roger Gatchet

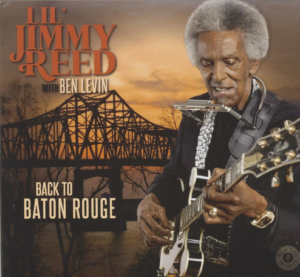

LIL’ JIMMY REED WITH BEN LEVIN

Back to Baton Rouge

Back to Baton Rouge

Nola Blue Records – NBR 023

Louisiana bluesman Lil’ Jimmy Reed (Leon Atkins) owes his distinctive stage name to a sad part of blues icon Jimmy Reed’s legacy. Atkins was a 20-year-old newbie on the blues scene when Reed, under the influence of copious amounts of alcohol, was unable to take the stage for a 1958 gig in Atkins’ adopted hometown of Baton Rouge. Lil’ Jimmy Reed was born when the show promoter, aware that the young Atkins dazzled local audiences with his spot-on imitation of Reed, ushered the incapacitated singer out the back door while Atkins was brought to the stage.

While Jimmy Reed is acknowledged as one of the founding fathers of postwar blues (thanks to uncomplicated but super memorable hits like Big Boss Man, Bright Lights, Big City, Honest I Do, and Ain’t That Loving You), numerous similar accounts of Reed being too intoxicated to perform made him a tragic figure in the blues world.

Co-written by 85-year-old Lil’ Jimmy Reed and Ben Levin to recount that fateful turn of events, They Call Me Lil’ Jimmy is one of the ten tracks on Back to Baton Rouge that Reed recorded with the 23-year-old blues piano prodigy out of Cincinnati. Although Reed says he never met his namesake, the similarities in their sound, approach, and performing style—sans the wipe-out drunk parts—are unmistakable, such as a reliance on boogie-soaked rhythm guitar patterns, simple turnarounds, and ever-present rack-mounted harmonica.

The five originals and five covers don’t break any new ground sonically or lyrically, but they deliver a simplicity and sincerity to the “down-home” style of blues that has been Reed’s trademark since he began pursuing a music career in the 1990s following a 20-year stint in the US Army. Levin and Reed are joined by Levin’s father, guitarist Aron Levin, bassist Walter Cash Jr., and drummers Ricky Nye and Miss Shorty Starr.

The album opens with Jimmy Reed’s up-tempo shuffle Down in Virginia. Lil’ Jimmy lays down a percolating solo on Wish You Wouldn’t as he laments the time-honored toll playing blues can have on relationships, “You get so jealous when I’m on my job / I’m a bluesman.”

Levin shows off his prodigious skill on the 88s on the ode to the young bluesman’s hometown, Cincinnati’s the Place to Be, and on the rollicking shuffle of Joe Liggins and His Honey Drippers’ In the Wee Wee Hours.

Engine Light, with its sinewy feel and Reed’s resonant voice, is held back by a sleepy groove, but the rhythm section kicks it up a notch and carries the closer, Slim Harpo’s Mailbox Blues.

On Back to Baton Rouge, Reed and Levin successfully straddle the line between paying homage to the past and presenting fresh takes on the blues in a collaboration between two musicians at different ends of the career spectrum.

—Rod Evans

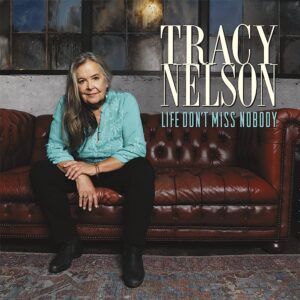

TRACY NELSON

Life Don’t Miss Nobody

Life Don’t Miss Nobody

BMG – 538870092

What a pleasure to have a new album from Tracy Nelson. Despite the album’s title—which cuts more than one way, of course—we’ve missed her; it’s been more than ten years since her last album, and she’s been accumulating material for a while now, showcasing the musical styles she loves. Nelson, who came on the scene as lead singer for the rock band Mother Earth, is as comfortable singing a gospel tune or pop standard as she is singing a blues song, and she traverses many musical landscapes with her vibrant, dynamic vocals. She’s joined on the album by many guests including, among others, Charlie Musselwhite, Jontavious Willis, Marcia Ball, Irma Thomas, and Willie Nelson.

The album gets the party started with Nelson’s rollicking and rolling take on the traditional Strange Things Happening Every Day, a jump blues that features Kevin McKendree delivering cascading roadhouse piano runs and Mike Henderson driving the song with his searing lead guitar licks. Mickey Raphael’s mournful harmonica wails under Nelson’s soaring vocals on the gospel-inflected There Is Always One More Time, which features the ethereal background vocals of Dianne Davidson, Vickie Carrico, Reba Russell, and Issac Ferguson Dillard. Nelson takes us to church on her version of this Doc Pomus / Ken Hirsch–penned song. Willis and Nelson trade lead vocals on the striding, slow-burning Your Funeral and My Trial, on which Willis also contributes shimmering resonator guitar licks. The minor chord title track unfurls atmospherically, laying down a chamber blues featuring Steve Conn’s lush piano. Nelson turns in a jaunty, St. Louis toodle-oo version of Ma Rainey’s Yonder Come the Blues, with Conn again on the barrelhouse piano. Ball and Thomas join forces with Nelson on the scampering, rollick-across-the-dance-floor I Did My Part, and the three join up again—with Dianne Davidson, Vickie Carrico, and Reba Russell—for a swaying, good-times take on Chuck Berry’s Brown-Eyed Handsome Man, and you can feel the spirit of the singers pouring out of the speakers. They’re having a good time singing, and we can’t but help feel the same way while we’re listening. Nelson includes two versions of Hard Times on the album: one version features Conn on accordion, Jim Pugh on B-3, and the exalted background vocals of Dianne Davidson, Vickie Carrico, and Reba Russell; the second version is a spare one featuring Nelson’s vocals and her 12-string guitar. In each version Nelson ably captures the essence of the song, but in the first version, she turns it into a gospel-inflected anthem. The second version closes the album, and it’s a fitting outro.

It’s good to have Tracy Nelson back, and she’s playing at the top of her game these days. There’s not a bad song on Life Don’t Miss Nobody, which showcases Nelson’s way with a song; she inhabits every song she sings, living in it and lingering over every nuance, and then delivers it to us in her singularly stunning vocals. Let’s hope it’s not another ten years before Nelson releases another album.

—Henry L. Carrigan Jr.

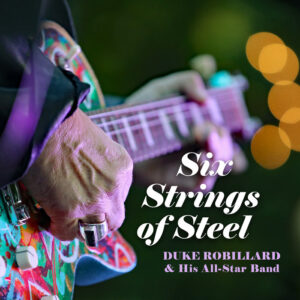

DUKE ROBILLARD & HIS ALL-STAR BAND

Six Strings of Steel

Six Strings of Steel

MC Records – MC-0092

Someone in London once spray-painted the absurd slogan “Clapton is God” on a wall. If you are really going to call someone that, then Duke Robillard would be a better fit. His own T-shirt refers to him more modestly as “The King of Strings.” Duke Robillard is indeed a genuine guitar royal, one of the quintessential guitarists of our time. As one of the most desired session guitarists on the planet, the maestro garners equal respect in the blues, swing, rock ’n’ roll, and jazz realms. There are very few players alive today who can maneuver across such a wide genre arena with unbridled virtuosity, refined taste, and sophistication. His resume is unmatched, having played on more than 50 albums. He has toured with Bob Dylan, Tom Waits, and Robert Gordon. He was a founding member of Roomful of Blues and played with the Fabulous Thunderbirds. He produced albums for Joe Louis Walker, Jimmy Witherspoon, Jay McShann, and Otis Clay. The resume is endless.

Even the biggest jazz snobs will tip their hat to the W.C. Handy blues award winner. His two albums with Herb Ellis, Conversations in Swing Guitar and the follow up, More Conversations in Swing Guitar, won international acclaim even in the discerning jazz press. On Six Strings of Steel, he stepped back to the music that influenced him as a teenager, a potpourri of styles from early rock ’n’ roll to surf guitar. He kicks it into overdrive with the help of his hot All-Star bandmates Marty Ballou (bass), Mark Teixeira (drums and percussion), Doug James (sax), and Bruce Bears (piano).

Git with It! is an early roots rock instrumental by Barney Kessel. The Smiley Lewis song Shame, Shame, Shame continues the fast, early rock vibe. The soulful original Robillard song In Perfect Harmony takes us into a Motown/R&B groove. He delivers a swift cover of Dylan’s Watching the River Flow, featuring Katie Shore on fiddle. Billy in the Lion’s Den by Leo Parker is a jazz swing instrumental interplay with saxophonist Doug James. They hit Fats Domino’s I’m Gonna Be a Wheel Someday perfectly. Robillard does justice to Ike Turner’s Take Your Fine Frame Home. They play a lovely version of Lowell Fulson’s Lovin’ You. Things fittingly end it with a bang, covering Link Wray’s ever dynamic surf rock classic Rumble.

The accolades for Six Strings of Steel could flow way beyond this short review. Once you drop this into your music player it will be stuck there on heavy rotation because it rocks the house and rolls with sheer musical pleasure. It’s exactly what we expect from a virtuoso like Robillard.

—Frank Matheis

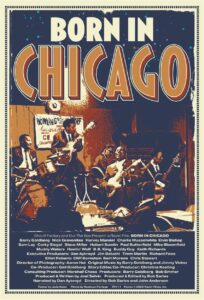

VARIOUS ARTISTS

Born in Chicago

Born in Chicago

Co-directed by Bob Sarles and John Anderson

Produced by Jim Belushi and Elliot Roberts, written by Joel Selvin, narrated by Dan Aykroyd

Ravin’ Films, released by Shout! Studios

Born in Chicago is a 77-minute, rapid-paced documentary with excellent sound and video quality that manages to shoehorn an impressive amount of great music in and around a sound-bite style narration with interview snippets of notable musicians and industry professionals of the era.

The title references both the song Born in Chicago, penned by Nick Gravenites and popularized by the Paul Butterfield Band in the 1960s, as well as the premise that Muddy Waters’ arrival in Chicago set off a seismic change in blues music, and that his blues had further reverberations in the world of rock, after the Butterfield Blues Band and their coterie adopted it and popularized it for white America.

As someone who himself was “born in Chicago” and was close to the scene in the years subsequent to the core period of this film, this writer can relate to that premise, but knows it’s more than a bit over-simplified.

One great strength of the film is the interview material, much of it borrowed from other sources. Aside from a few that seem self-serving, many are genuinely charming in the unvarnished excitement and affection the subjects have for the music and musicians. In vintage footage, guitarist Michael Bloomfield, who died in 1981 at the age of 37, speaks of the blues as if he were 15 again and discovering it for the first time—for him the thrill of discovering Chicago blues never lost its freshness. Musicians Charlie Musselwhite, Corky Siegel, and Elvin Bishop too talk with great humility of their entry into the world of South and West Side blues clubs and of the familial company of great musicians such as Big Walter Horton, Otis Rush, Howlin’ Wolf, and Little Smokey Smothers.

Dan Aykroyd’s narration (or writer Joel Selvin’s script) is pure hyperbole and schmaltz in places: Chicago blues “began with Muddy Waters,” Aykroyd states, which completely dismisses the vibrant Chicago music and recording scene of previous decades, and ignores the fact that many of the very performers shown in the beginning footage (all but one unidentified)—Daddy Stovepipe, Robert Nighthawk, Carrie Robinson, Jim Brewer, John Lee Granderson, Arvella Gray—were performing in Chicago before Muddy Waters arrived in 1943. But there’s no question Muddy’s impact was monumental, as B.B. King says, “Muddy Waters did more for blues than any of us because he lit up Chicago.”

The narration suggests that when Bloomfield began going to South Side blues clubs, it was “an entire world that existed without anyone in the white community knowing.” That would surprise photographer Ray Flerlage, record producers Bob Koester, Eli Toscano, and several others, not to mention the Chess brothers who owned the South Side Macomba Lounge and had been recording blues and jazz musicians for more than a decade.

It is also stated that there had been no blues on Chicago’s North Side until the Butterfield band brought it to Old Town, when in actuality there had been a Black community just to the west of Old Town that was rife with small blues clubs until “urban renewal” wiped it off the map around this same time.

“In some cosmic way,” the narration further states, “these older Black blues musicians knew who these young white men were . . . and welcomed them . . . These kids found something they couldn’t find at home, they found love.” Perhaps a tad outrageous, apart from the fact that most of the older musicians were genuinely accepting and warm towards the newcomers.

Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones makes the hindsighted assertion that their release of the 45 r.p.m. cover of Howlin’ Wolf’s Little Red Rooster in 1964 (when he was only 20 years old) was their attempt to get white American kids into the blues. To their credit, they did insist that Howlin’ Wolf appear with them on the popular American TV teen show Shindig! and had many Black blues and soul acts open on their subsequent tours.

Much is made of Bob Dylan “going electric” at Newport in 1965 with members of Butterfield’s band, as well as the impact of blues on the white rock scene. Bloomfield, who helped convince Bill Graham and Chet Helms to book the older blues musicians, says passionately, “Kids do have enough taste to dig the real thing.” Helms later smugly brags, “We resurrected the careers of some somewhat obscure blues artists.” Debatable, but the brilliantly designed posters for those San Francisco rock shows were perhaps the best graphic promotion that many of those blues musicians ever received.

Aykroyd states toward at the end, “The original masters . . . lived out their lives in prosperity and acclaim they couldn’t have imagined,” and, “The original masters have been recognized and honored and many inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame,” as if acceptance in the white rock world was the ultimate measure of success.

Born in Chicago remains a highly entertaining film in terms of the music and the reminiscences of the principal players of this seminal period, but some of the opinions should be taken with a grain of salt.

—Justin O’Brien

LEONARD “LOWDOWN” BROWN

Blues Is Calling Me

Blues Is Calling Me

Music Maker Foundation – MMCD211

Leonard “Lowdown” Brown is an unusual Houston blues artist, recently becoming a septuagenarian performer who some might consider a newcomer, at least on the national stage. But for well over 40 years, the guitarist, singer, and songwriter—keen on the notion that making music is its own reward—has happily carried on in relative obscurity. Born in Arkansas in 1953, he grew up in Gary, Indiana, one of ten children in a gospel-singing family. Upon completion of a two-year technical training program, Brown made a career move to Texas in 1980, establishing himself in an industry job for years to come. But not long after arriving, he also began exercising his passion for the blues by participating in weekly jam sessions at certain Houston venues. As his exquisite guitar playing and soulful vocalizing gained notice, he eventually formed his own band and started booking weekend gigs on the local circuit. Over subsequent decades, he established himself as a stalwart of the Bayou City live music scene but, until recently, remained only sparsely recorded and hardly known outside of his adopted home turf. Now, thanks to Brown’s affiliation with the nonprofit Music Maker Foundation—which has introduced him to larger audiences via festival appearances, a performance on the soundtrack for the National Geographic special series America the Beautiful on Disney+, and this fine new album—that situation is changing for the better.

Prior to such developments, Brown’s recordings were scarce—and in some cases released without authorization. The notorious producer Roy C. Ames included one track by Brown on the 1992 CD compilation Texas Guitar Greats, Vol. 2, another on 1993’s Blues as Big as Texas, Vol. 2, and a third on 1995’s New Blues from Texas, all issued on the Collectables imprint—triggering a lawsuit (in which Brown’s fellow plaintiffs included Big Walter Price, Jimmy “T-99” Nelson, Joe “Guitar” Hughes, the descendants of Weldon “Juke Boy” Bonner, and numerous others). In 1997 Brown self-produced a homemade CD titled Birth of the Blues, which for a while was available to purchase during set breaks at his nightclub gigs. Then in 2002 he appeared as a featured guest, on lead vocals and guitar, on one track of the Calvin Owens Blues Orchestra album The House Is Burnin’ (Sawdust Alley Records).

Blues Is Calling Me thus marks Brown’s first proper album to be issued at large. It’s a fitting debut for this veteran performer, highlighting his laid-back fervor on electric guitar, passionate singing, and compositional skills. The setlist comprises ten tracks, nine Brown originals plus an upbeat and jazzy interpretation of the gospel standard You Gotta Move. The frontman is effectively backed in the studio by his producer Ardie Dean on drums, as well as Microwave Dave Gallaher on guitar, Tony Grady on bass, and Dan Hochter on keys and bass. In a Music Maker website article Dean refers to Brown as the “most soulful male voice” on the Foundation’s roster of artists, and this production shows why. Brown’s expressive baritone vocalizing—which flows forth in a smooth yet spirited manner, stirringly raw in the right places—might well be his strongest quality. But Brown also impresses with his elegantly lowdown guitar work as he fingerpicks smoothly melodic solos and subtly stinging riffs.

On the opening track, Juke Joint, the lyrics might not aspire to profound poetry, yet Brown’s reedy voice communicates a palpable depth of feeling, a deep desire to find solace in the communal rites of a neighborhood bar. Meanwhile, one of the best-written songs, Find a Bridge, speaks from the point of view of a hurricane survivor trying to escape a flood-ravaged city but in need of a bridge to “get to the other side.” Significantly, it is not a slow and mournful tune but a moderately paced shuffle in which the tempo reflects the protagonist’s willful determination. Moreover, the central motif—of crossing a river to find some kind of salvation on the opposite shore—echoes a common trope from the early days of Black American song, imbuing the piece with a timeless universality. Among other standouts, Lowdown’s Blues is the lone instrumental number, a shuffle that really swings. Juiced by riffs from an uncredited horn section, it rides a gracefully canorous guitar solo, no need for words. But the jaunty title track, among others, also showcases Brown’s capacity for sublimely restrained six-string articulation.

This “debut” album has surely been a long time coming. Likewise, Brown has been a long time singing, gigging, creating—responding to the call of the blues.

—Roger Wood

RIP LEE PRYOR

Sugar Daddy Blues

Sugar Daddy Blues

No label – No #

Rip Lee Pryor, whose father was Chicago harmonica legend Snooky Pryor, has adopted his dad’s tubular, broad-toned harp style, his love of deep-pocketed shuffle rhythms, and, apparently, his irony-toughened sense of humor. (The opening number here, Stuck on Stupid, sounds as if it was inspired by the same muse that channeled How’d You Learn to Shake It Like That through Snooky back in the late 1980s.) Unlike Pryor Sr., though, Rip Lee is a multi-instrumentalist; he is credited with all the instruments on most of the offerings here—a precise breakdown is not given, but assuming that everything was played live in the studio I hear harp, rhythm and lead guitar, bass, and drums.

Pryor’s voice, again like his father’s, is seasoned by a wide vibrato, although his timbre sounds more youthful, even callow in places. That doesn’t detract from his effectiveness, though; blues has always been “grown folks’ music” by virtue of the stories it tells and the worldly, life-hardened perspective reflected in both the lives and personas of its most important purveyors, and this is the aspect of the music and its message that Pryor conveys. Invocations of ancestral spirits abound—Mess Up This Good Thing, though an entirely original composition, echoes Rice Miller’s Don’t Start Me Talkin’ in both its structure and Pryor’s vocal delivery; She’s My Little Girl is based on the timeless Sitting on Top of the World / Someday Baby / You’ve Got to Move theme. Echoes of Wolf’s Three Hundred Pounds of Joy, possibly by way of Bo Diddley, resonate through Natural Born Lover Man; I Wanna Rock You Baby, with its loping shuffle accentuated by Pryor’s tongue stops, is probably the purest example of the Snooky Pryor harp legacy on offer here.

Two tracks, Sugar Daddy Blues and the provocatively titled Brazilian Brothel (whose lyrics do not disappoint—“I knew right then we’s gonna have a lot of fun / ’cause I took a blue pill before the task begun”) feature Jon Atkinson on guitar, Troy Sandow on bass, and Ronnie Smith (Brothel) or Perdis Wilson (Sugar Daddy) on drums. Without more complete credits, it’s a little unclear why this was done, but it’s intriguing to hear Pryor interacting with others as deftly as he negotiates his way through his own entirely self-realized musical landscapes.

Rip Lee Pryor’s discography is not extensive, but judging from what’s here, it would appear that he’s had a lot to offer for quite some time, and we can feel confident that there’s plenty more where this came from.

—David Whiteis

MISTY BLUES

Outside the Lines

Outside the Lines

Guitar One Records – No #

Misty Blues founder and frontwoman Gina Coleman was born and raised in the South Bronx, where she grew up surrounded by a mix of R&B and salsa. After earning a degree in English from Williams College, Coleman got her first taste of performing when she sang Janis Joplin’s Mercedes Benz at an open mic night. Eclecticism and a sense of adventure remain key ingredients in Misty Blues’ music. Their latest release, Outside the Lines, lives up to its name, mixing the blues with heavy doses of jazz and funk to create a unique, contemporary sound.

Opener Where Your Blues Come From grabs the listener’s attention as Aaron Dean’s sax, Diego Mongue’s distorted guitar, and David Vittone’s high-octane organ riffs create a dense wall of sound. Coleman’s dynamic alto voice has enough power to cut through the mix. I Don’t Sleep follows the blues tradition of celebrating perseverance in the face of adversity. As Coleman and guest Petri Byrd exchange verses, Benny Kohn’s keyboards add a taste of jazz to the arrangement. Every Which Way is a kinetic mix of blues and funk that’s sure to get butts out of chairs. Kohn shines again with keyboard licks that are equal parts Stevie Wonder and Herbie Hancock. Tasty drum breaks from Rob Tatten keep the groove moving.

Days of Voodoo and Laughter sports a low-key arrangement that allows Coleman’s vocal chops and skill as a songwriter to shine brightly. As Coleman sings, “When I finally shed my skin / I’ll be coming back again to take you higher,” it sounds like she’s directly addressing the listener. Dare to Dream features more heartfelt vocals and some of the album’s most stunning musicianship. Multi-instrumentalist Mongue, who is Coleman’s son, demonstrates incredible skill as a bass player. Clearly drawing inspiration from jazz/fusion legend Jaco Pastorius, Mongue’s aching harmonics and lyrical lines enhance the tune’s beauty.

Misty Blues’ skill and boundless creativity conjure up sounds that go well beyond what one expects to hear on a blues album. Listeners who appreciate innovation will not want to miss Outside the Lines.

—Jon Kleinman

BETTYE LAVETTE

LaVette!

LaVette!

Jay-Vee – JV2023

Like her 2018 Grammy-nominated album Things Have Changed that focused on songs composed by Bob Dylan, Bettye LaVette’s new release, LaVette!, is dedicated to material from the catalog of one songwriter. This time around the focus is on Randall Bramblett, the veteran singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, whose extensive work as a sideman and leader embodies the Americana genre. The 11-song playlist of Bramblett songs that LaVette covers invests the album with a cohesive, soulful, bluesy, funk sound. That cohesiveness also owes a lot to drummer Steve Jordan’s dual role as producer (his third time around with LaVette) and the masterful, in-the-pocket core band that he’s assembled—L. Leon Pendarvis on keyboards, Pino Palladino on bass, and Larry Campbell and Christopher Bruce on guitars. Jordan also taps a series of guest musicians that bring a distinctive flare to many of the performances. In addition, and perhaps most importantly, that cohesion must be credited to LaVette. She inhabits the songs and delivers them with a controlled fire and immediacy that puts a personal stamp on them.

Over the years, Bramblett has worked with Bonnie Raitt, and she comes to mind with the slide guitar–driven bluesy funk of See Through Me. LaVette’s ability to ride on a groove is apparent on Don’t Get Me Started with its surging Hammond B3 courtesy of Steve Winwood. She delivers the stripped-down Lazy (And I Know It) with a dramatic passion that makes the introspective lyrics seem if they are emerging directly from her inner consciousness. LaVette’s roots in 1960s soul music come to the fore on In the Meantime, a tune that sounds like it was plucked from the Stax catalog with its interplay of chiming rhythm guitar from Ray Parker Jr. and Campbell’s pedal steel. The icing on the cake is John Mayer’s dramatic guitar solo. Spurred on by a punchy horn section led by James Carter’s muscular baritone saxophone, LaVette invests Hard to Be a Human with an existential ache. Campbell’s pedal steel sets the tone for the country-flavored ballad I’m Not Gonna Waste My Love that the singer delivers with an impassioned heartbreak. She shows she can rock the blues on Plan B, which boasts some searing lead guitar from Bruce. The highlight of the set is Mess About It. Jordan kicks it off with a snare hit and then locks into an unrelenting backbeat. Parker, Campbell, and Bruce weave their guitars together in a rhythmic frenzy; Palladino’s bass pulses; and Pendarvis’ electric keyboard dances through the mix. Right in the middle of it all Jon Batiste drops in a jazzy acoustic piano solo. This is James Brown territory. Talk about a singer locked into a groove with a band! She screams and squeals and hollers, evoking Brown but always making it clear that this is Bettye LaVette, and she is taking no prisoners.

It took a lot of years and hard work for Bettye LaVette to find the recognition she deserves. LaVette! makes it clear that that she’s on top, and that’s exactly where she intends to stay.

—Robert H. Cataliotti