TAJ MAHAL

TAJ MAHAL

Savoy

Stony Plain Records – SPCD1470

Taj Mahal is music royalty. A prime exponent of both Americana and so-called “world music” long before either of those labels came into widespread use, he’s a bluesman at his core. His musical vision has always been wide-screen, from his days with Ry Cooder in the Rising Sons to the present day. That band cut the Goffin/King tune Take a Giant Step even before the Monkees got around to it. Taj Mahal has always been ahead of his time, and outside of it.

On his latest release, Savoy, the Blues Foundation Hall of Famer and three-time Grammy-winning roots legend takes a journey into music’s past. Savoy is a collection of songs from the big band/swing era of the 1930s and ’40s. Across 14 standards, 80-year-old Taj Mahal applies his blues-based sensibility to jazz tunes, and results are remarkably timeless. A revered and accomplished songwriter in his own right, on Savoy Taj Mahal reasserts his primacy as one of music’s foremost interpreters of the work of other composers.

Taj Mahal introduces the album with some personal reminiscences. A jazz band and silky-smooth female vocal chorus back him, playing Stompin’ at the Savoy. His singing doesn’t come in until midway through the song. The approach sets the stage for a collection of studio recordings that feels like a live performance. He even throws some good-natured scat vocals in toward the song’s end, sounding for all the world like a 21st-century Louis Prima.

The song selection leans toward the familiar, but in Taj’s capable hands, each and every tune feels fresh and new. The swaggering I’m Just a Lucky So-and-So leads into the understated and slightly forlorn Gee Baby Ain’t I Good to You. He turns George Gershwin’s evergreen Summertime into an up-tempo swing tune. Duke Ellington’s Mood Indigo is delivered in a more conventional manner.

Taj’s reading of Louis Jordan’s Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby is more understated than both Jordan’s original and Joe Jackson’s Jumpin’ Jive–era remake, but the song’s sly character is wholly intact. Sweet Georgia Brown gets a jazz manouche arrangement. Continuing the back-and-forth between reverence and reinvention, Baby It’s Cold Outside features an arrangement quite close to the way most listeners know it.

Jordan’s relentlessly up-tempo Caldonia reminds listeners of the through line that connects big band jazz and rock ’n’ roll. Benny Golson’s instrumental classic Killer Joe gets some shoop-doo-wah vocalese applied to it; the song showcases the record’s instrumental expertise.

Savoy concludes as it simply must: with a cover of One for My Baby (And One More for the Road), a song designed as a set-closer. Harold Arlen’s classic saloon song is known as a Frank Sinatra vehicle, but it has been effectively covered by many greats from Fred Astaire to Willie Nelson. And as he does with each and every of Savoy’s 14 songs, Taj Mahal makes the late-night weeper his own.

—Bill Kopp

ERNIE VINCENT

ERNIE VINCENT

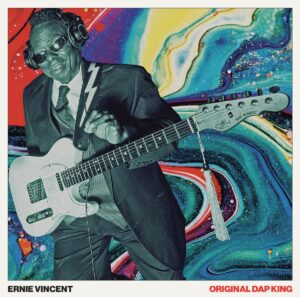

Original Dap King

Cornelius Chapel Records – CCR61

Guitarist and singer Ernie Vincent established himself on the New Orleans music scene back in the mid-1960s. He has plied his trade supporting a wide array of R&B, blues, and funk artists, including New Orleans legends Ernie K-Doe, King Floyd, Eddie Bo, Tommy Ridgley, Oliver Morgan, Jesse Hill, and Monk Boudreaux, as well as artists from beyond the Big Easy, such as Solomon Burke, Joe Tex, and Z.Z. Hill. Primarily a sideman, Vincent did score a solo hit with Dap Walk (1972), an explosive, wah-wah guitar–driven funk excursion (that provided the inspiration for the Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings band name). With Original Dap King, Vincent steps into the spotlight for a ten-song set of old-school, funky blues and R&B with the help of a solid backing crew that features Jimbo Mathus on keyboards, Matt Patton on bass, and Bronson Tew on drums. Patton and Tew also serve as producers, crafting a stripped-down, dynamic sound that highlights Vincent’s groove mastery.

Original Dap King features a range of material that allows Vincent to showcase his formidable skills and versatility as a guitarist, from the swaggering vintage wah-wah sound on Body Shop to the shimmering single-note runs on the southern soul–styled Midnight Rendezvous, from the rocking Hendrix-inspired fuzz tone on Blues Filler to jagged-edged slow blues of Seven Sisters. Vincent boasts a deep, gravel-road voice that often brings Pops Staples to mind, and like Staples, his range is limited, but he works with what he’s got and delivers the songs with a genuine charm and conviction, which is especially apparent on the haunting, Curtis Mayfield–like Black and the rocking, barrelhouse R&B of Early Times. This album should establish Ernie Vincent as a leader, and hopefully he’ll be a force to be reckoned with on the contemporary blues, R&B, and funk scene.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

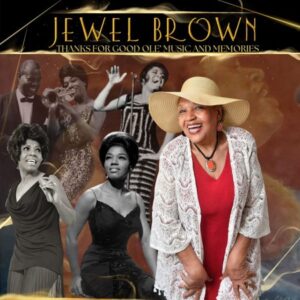

JEWEL BROWN

JEWEL BROWN

Thanks for Good Ole Music and Memories

Nic Allen Music Federation – MF22JB010

The Texas songstress Jewel Brown launched her professional career as a child prodigy in the late 1940s, debuted on Duke Records in ’55, and toured globally as a featured singer with Louis Armstrong’s ensemble through most of the ’60s. Following a period of quasi-retirement from the music business, she re-emerged with the New Orleans–based Heritage Hall Jazz Band in the early 2000s, then collaborated with the Houston blues guitarist Milton Hopkins on an acclaimed 2012 album and with the Japanese swing group Bloodest Saxophone on another album two years later. However, as the venerable vocalist (cover artist for LB #236) recently told this writer, she “ain’t done yet.”

Now at the age of 85, Brown is back with a ten-track release that not only, as the title suggests, engages in some tender retrospection but also introduces seven new tracks on which—for the first time in her long and distinguished career—she earns co-writer credits. As such, this is Brown’s most personal album, featuring a jazzy blend of songs infused with her elegant yet downhome charisma and, in many cases, her own words. Backed by a super-tight nine-piece band directed by her producer, co-writer, and keyboard/organ player Nic Allen, Brown delivers an energized yet intimate artistic statement, full of attitude and gratitude.

As the spry singer is quick to emphasize, this project was inspired by the late, great jazz and R&B musician Joe Sample—like Brown, a native Houstonian. Following a lengthy Los Angeles–based career, Sample had returned (ca. 2010) to live in his hometown, where he reconnected with Brown. He also taught the graduate course Jazz Orchestra Project at Texas Southern University, where he met and mentored the young phenom Allen. Shortly before Sample’s death in 2014, he introduced Brown to Allen and urged them to work together—the start of a creative partnership that led to this new album. Given such an inception, it naturally culminated in a cool and contemporary jazz sound with a rootsy vibe that incorporates, but by no means is limited to, the blues.

While Brown showcases mostly original material, the setlist does include new versions of a couple of cover songs with longtime personal connections. The disc opens with the rumba-spiced Jerry—formerly a concert staple of Brown’s tenure with Armstrong and now, it seems, her signature song (which also graced her album with Hopkins). Likewise, the mellow romantic fantasy titled Song of the Dreamer (which she had also recorded earlier with Bloodest Saxophone) was written by Brown’s ex-husband, the late bandleader Eddie Curtis. But the third cover selection, somewhat surprisingly, is an appropriately funky interpretation of Which Way Is Up, the theme song of the 1977 film (starring Richard Pryor) of the same title.

Standout numbers among the original compositions include Pain and Glory, a spoken word performance delivered with soulful spunk by Brown, accompanied only by rhythmic background vocalizations in a jazz–gospel–doo-wop mode. On the Road is a laid-back meditation by a traveling performer who appreciates a supportive lover back home, and near the end it’s nicely garnished with a twist of scat-vocal improvisation. In contrast, over ominous instrumentation, Nitches and Glitches recounts wrongs suffered while Brown forcefully articulates a will to no longer tolerate such abuse. The set closer, How Did It Go, is a bluesy shuffle with a walking-bass line accented by exquisite guitar, over which Brown heartily sings and jives, interjecting sassy ad-libbed commentary along the way.

Through it all, a vivacious personality is present in the music. While it has been almost 70 years since she first recorded, these new tracks confirm that Jewel Brown remains vibrantly expressive today.

—Roger Wood

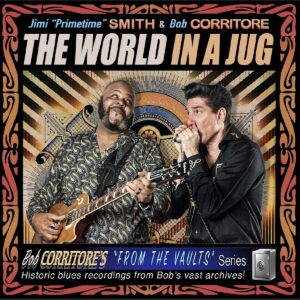

JIMI “PRIMETIME” SMITH & BOB CORRITORE

JIMI “PRIMETIME” SMITH & BOB CORRITORE

The World in a Jug

VizzTone/SWMAF – SWMAF 24

Guitarist Jimi “Primetime” Smith, profiled on the cover of the previous issue of LB, is a Chicago-born bluesman with deep roots. His mother, the late Johnnie Mae Dunson, was a noted songwriter and drummer who worked closely with Jimmy Reed; his childhood associates included Reed, Eddie Taylor, and other Chicago blues legends. Some of his earliest gigs included stints with Reed himself, as well as such figures as Big Walter Horton, Floyd Jones, and John Brim. Over the years he has slowly emerged from under those daunting shadows and cultivated a name for himself as both a deft soloist and an expressive vocalist.

Smith’s recorded output under his own name, though, has been relatively sparse until now. These sessions, recorded between 2017 and 2020 in Tempe, Arizona (the home base of co-producer and harpist Bob Corritore), showcase his roots blues chops at their most powerful and raw, buttressed by Corritore’s evocative harp work along with accompanists including, at various points, legends Bob Stroger (bass) and Henry Gray (piano), and a crew of lesser-known but no less dedicated younger-generation aspirants.

At times, Smith seems to be channeling Reed with almost eerie verisimilitude, especially when he takes on Reed chestnuts like the title tune and We Got to Stick Together (both penned by his mother, the latter recorded in live performance) or delivers a song of his own that has obviously been crafted to evoke the master as closely as possible (You for Me). On outings such as Love Her with a Feeling (credited here to Freddie King) and originals like the Muddy-esque Southbound, Walkin’, and Fire and Ice (also recorded live and featuring a torrid harp break from Corritore), his voice and guitar work are more personalized, but the overall sound continues to adhere closely to the spirit of Chicago blues’ postwar glory days. Elsewhere, though, as on the lithe, swinging Blinded, the moody, pop-tinged ballad In a Spin, and the jubilantly rocking Soul Food, he shows his gift for moving in fresher directions without losing the essence of Chicago tradition that lies at the root of his art.

Balancing dedication to tradition with forward-looking improvisational acumen in way that avoids both “moldy fig” purism and self-indulgent posing can be difficult. Jimi “Primetime” Smith, who learned his craft from some of the blues’ all-time masters but, like all musicians with “big ears,” has absorbed ideas and influences gleaned from a wide range of sources, is poised to join the ranks of John Primer and a handful of others who have mastered this rare art and continue to move it forward.

—David Whiteis

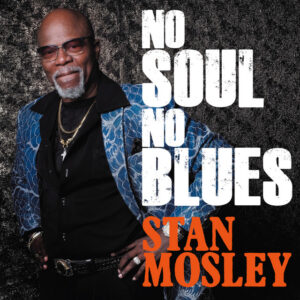

STAN MOSLEY

STAN MOSLEY

No Soul, No Blues

Dialtone Records – DT0032

Born and bred in Chicago, Stan Mosley has been tearing up the soul scene for decades, performing since the early 1970s and traveling up and down the chitlin’ circuit before breaking out as a headliner in the 1990s with his acclaimed releases for Malaco. Now based in Houston, Texas, the veteran soul singer and songwriter has joined forces with renowned Austin producer and label owner Eddie Stout to make his first blues record. And what a record it is. Cut live in the studio in just one or two takes—the winning formula that Stout has perfected on his Dialtone releases—No Soul, No Blues is the album that no serious fan of either genre should miss.

Backed by a flawless Texas band that includes ace Austin musicians Johnny and Jason Moeller on guitar and drums (respectively), the Texas Horns (Kaz Kazanoff, John Mills, and Al Gomez), Anthony Farrell on Hammond B-3 organ, and Mike Archer on bass, each track sizzles with electricity and energy that is palpable. Like Stout’s previous Dialtone productions, this release could easily be mistaken for something that was recorded 50-plus years ago when the music was in its heyday. There are no modern sweeteners here, or electronic crutches or punched-in overdubs, just consummate musicians locking in and playing together seamlessly as if they’ve been together for years.

As the title slyly conveys, you have to have soul to play the blues—hence no soul, no blues. Which makes Mosley a natural here. A scintillating set of both originals and well-chosen covers, his gritty, commanding voice lends itself perfectly to deep southern soul as well as hard-hitting old school blues, both of which are abundant on No Soul, No Blues. At 70 years old, Mosley is at the top of his game as a self-assured vocalist and performer as is plainly evident throughout the 11 cuts.

The super-charged opening track, I’m Back to Collect, sets both the mood and the bar with his searing take on Denise LaSalle’s defiant anthem highlighting Mosley’s tough, uncompromising vocals. He then moves deftly into the autobiographical Blues Man, declaring, “My name is Stan, I’m a soul man / But I’m gonna sing the blues tonight for you / Now you know who I am—I’m a blues man.”

A powerful and punchy version of Little Milton’s 1962 classic Losing Hand follows with the tight horn section going squarely toe-to-toe with Mosley’s tough-as-nails vocals. The pace then slows a bit on the smoldering What You Need, another Mosley original where he demonstrates his melismatic chops on the sultry ballad as he promises, “If I can’t be what you want, I’ll be what you need.” Label mate Crystal Thomas, a very compelling blues and soul singer herself, joins him on the next two numbers: a very funky (and fun) duet on Wilson Pickett’s all-bark-and-no-bite Stomp and a tour de force rendition of the rhythm and blues chestnut I Can’t Get Next to You that’s equal parts Temptations, Al Green, and Mosley/Thomas. As with the entire band, the strong and at times playful chemistry between the two powerhouse vocalists is apparent and one of the many highlights of the album.

Mosley and company next offer up a fine treatment of the guilt-ridden Right Next Door (Because of Me), which follows a similar path to Robert Cray’s signature rendition, but with a bit more bite. I Smell a Rat features an irresistible groove with some very satisfying interplay between Mosley’s assured vocals and Moeller’s stinging guitar lines. Mosley’s third composition here, Change of Heart, is a beautifully optimistic and socially conscious up-tempo plea that showcases his sensitive songwriting skills with the thoughtful refrain “Gotta have a change of heart, within us is where it starts.” The pace slows down again on the lusty ballad A Woman Needs to Be Loved, which serves as a fine tribute to one of Mosley’s influences, Tyrone Davis. The set closes out with another fine original, Undisputed Love, a supreme slow blues showcasing Mosley’s pitch-perfect, pleading delivery, once again marvelously complemented by Moeller’s tasteful and exacting guitar work.

As he excitedly exclaims, “That’s it, that’s it, that’s it, that’s it!” immediately following the explosive opening track, Mosley’s spontaneous shout of satisfaction could have easily described just about every cut on No Soul, No Blues. It’s that good from start to finish. Whether you love soul, love the blues, or love them both, do yourself a favor and buy this recording. It’s not only a leading contender for record of the year, but should also make the list for the decade.

—Gene Tomko

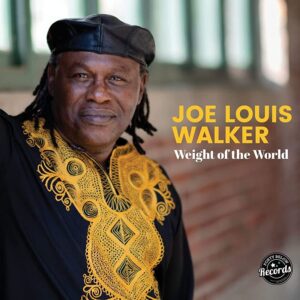

JOE LOUIS WALKER

JOE LOUIS WALKER

Weight of the World

Forty Below Records – FBR-030

Joe Louis Walker has been around and seen a few things in his 74 trips around the sun. The West Coast blues icon isn’t bashful about dishing out some of his hard-earned wisdom and still-fierce guitar and vocal chops on his new album, Weight of the World.

The Blues Hall of Famer and six-time Blues Music Award winner joins forces with Grammy-nominated producer Eric Corne on the album that explores his numerous influences and genre-bending tendencies. The ten tracks cover a lot of territory, from gutbucket blues, to soul, gospel, and take-no-prisoners rock. The effort also displays Walker’s deft touch at stepping outside the tried-and-true blues themes of infidelity and boozy good times. True to its title, several tracks feature socially aware and introspective examinations of the human condition.

Walker plied his trade in smoky taverns in and around his native San Francisco for a couple of decades before he recorded his debut solo album, 1986’s Cold Is the Night. A guitar prodigy, he began playing in clubs as a teenager, forming friendships with the likes of Mike Bloomfield. He also waded into the San Francisco Flower Power scene alongside members of the Grateful Dead. His journey included a stint in a gospel band, earning a couple of college degrees (in English and music), and forming musical alliances with people like Steve Cropper, Keb’ Mo’, and Eric Gales.

Walker cuts right to the existential chase on the buoyant and funky title track, as he sings “Can’t move with the weight of the world sitting on my shoulder / so we watch it burn / until we all finally adjourn.” A yearning Walker solo lifts the song to the stratosphere.

Corne, who’s a writer or co-writer on five of the tracks, flashes his penchant for traversing socially conscious subjects over beds of sumptuous blues, soul, and roots music.

On Matter of Time, Walker tackles the inequities in the American justice system: “There’s just one matter of fact / you pay for the justice you get,” and the inevitability of time: “Time will tell, so I’ve been told / But I don’t believe anybody knows what the future will hold / You gotta wait until you get old.” He even pays homage to Sam Cooke: “I heard a change is gonna come / I hope it’s soon before I’m gone.”

Walker breaks out his classical guitar on the poignant Hello It’s the Blues, which casts the blues as a caring, if not completely benevolent lover: “No matter what you do / You’re gonna need me again and again and again.”

Waking Up the Dead, with a steamy second line groove and Walker’s devilish slide guitar, decries charlatans and snake oil salesmen. Walker’s rock ’n’ roll prowess shines on Count Your Chickens and Blue Mirror, while he explores cool jazz on the closer, You Got Me Whipped.

On Weight of the World, Walker proves that a veteran bluesman can deliver fresh, well-crafted and relevant modern blues.

—Rod Evans

THE CASH BOX KINGS

THE CASH BOX KINGS

Oscar’s Motel

Alligator – ALCD 5011

Co-leaders Joe Nosek (on blues harp and vocals) and Oscar “Mr. 43rd Street” Wilson (vocals) know their way around the high-energy Chicago variant of the blues. Save for the sonic clarity that comes from working in a 21st-century recording studio, Oscar’s Motel’s opening track could be mistaken for a genuine 1940s article. The title tune is a gritty slice of Howlin’ Wolf–inspired bluesiness.

But the variety contained in the Cash Box Kings’ musical bag means that the group quickly takes the music elsewhere. A tight horn section figures prominently in Down on the South Side, with a rock-solid rhythm section underpinning. Then it’s back to vintage textures for a stripped-down, drummerless treatment of Muddy Waters’ Please Have Mercy. Nosek’s wonderfully distorted harp wails throughout.

With its phone-call intro, the shuffling band original I Can’t Stand You is a blues cousin to the Big Bopper’s Chantilly Lace. But lyrical references to Facebook plant the song firmly in the here and now. Deitra Farr’s guest vocal works nicely alongside Nosek and Wilson.

Postwar jump blues/R&B textures come to the fore on Hot Little Mess, a tune that swings hard. That track—like all 11 on the record—showcases the fun that the band is having while making this music. Initially more serious in nature is the gospel–meets–field holler flavor of Nobody Called It the Blues. The song’s “live in the studio” vibe is one of the keys to its effectiveness.

Sonny Boy Williamson II’s Pontiac Blues gets a dance blues reading from the band; listen and you can almost feel the juke joint sawdust beneath your feet. And since that tune will likely leave dancers out of breath, Trying So Hard follows on its heels. The song slows the tempo to a grinding crawl. The tension is palpable, giving the song the character its lyrics demand. The dialogue between Nosek’s overdriven harp and guest guitarist Shoji Naito’s stinging slide guitar is a delight.

She Dropped the Axe on Me demonstrates songwriter Nosek’s skill at crafting a fresh tune out of familiar elements. And the song provides one of many opportunities on Oscar’s Motel to enjoy the expressive and playful piano work of Lee Kanehira. I Want What Chaz Has is another fun number that hints at what the band would be like live onstage. The gang backing vocals conjure memories of Louis Prima or Louis Jordan. And despite its holiday theme, the rocking album closer Ride Santa Ride is a fun tune most any time of year.

Joe Nosek’s varied and always note-perfect production values showcase the strengths of the band and shine a light on the Cash Box Kings’ variety. On their tenth album the band show no sign of losing any of the qualities that make them special. Checking into Oscar’s Motel guarantees an enjoyable stay.

—Bill Kopp

MOJO IKE AND LADY VAL

MOJO IKE AND LADY VAL

Phoenix

No label – No #

Mojo Ike (or Magic Mojo Ike, born Ike Woods) is a towering figure in the Miami blues scene. With his searing, passionate electric guitar work and his expressive voice, Ike packs plenty of emotional content into his original songs. Joined on Phoenix by vocalist Lady Val (Val Woods, a.k.a. Mrs. Ike), he packs a wallop with nine memorable tunes.

A pop sensibility pervades the set. Phoenix presents a blues-informed framework in a widely accessible style, with vocals out front, lead guitar playing a strong supportive role, and rock-solid instrumental backing at the core. A sense of optimism shines through all of the songs.

Thank You Lord for Having Faith in Me settles into a gospel groove, but the tune adds in the sonic character of a romantic slow-jam blues; the combination works seamlessly. A love song is a love song, after all. Lady Val turns in a passionate, bravura performance, and the backing chorus (Sister Mary Beth, Isaac Woods, and JR Conner) is stellar.

Get Along is lyrically similar, but cut from very different musical cloth. An uncluttered chord structure gives the musical ensemble the opportunity to dig into the song’s grooves, underscoring the power of musical simplicity. Ike’s tasty guitar break is tantalizingly brief, leaving the listener wanting more.

The funkiest track on Phoenix is Feel Like Superman. With a slinky urban blues feel, it’s a showpiece of understated swagger. Playful lyrics (example: “Our love is made out of steel”) add to the appeal of the tune, and Ike’s lean licks help the arrangement double down on the head-nodding vibe.

There’s a smoky Albert King feel to Not for Rent. Lady Val’s sensual, moaning vocal positively simmers. Ike’s heavily reverbed lead guitar solo ranks among the finest instrumental moments on the album. It’s easy to imagine the track transformed into an extended workout in a live setting, with Ike taking the opportunity to stretch out and dig in even more.

The album features two well-chosen covers. Big Boss Man was a Jimmy Reed single in 1961, and the song was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame in 1990. The version on Phoenix features a stomping beat and spirited backing vocals that give it the feel of a tent revival. Ike’s stinging lead licks take the song another place, and the combined effect is superb.

Phoenix also features a reading of Freddy Harris’ New Children of the World. Harris wrote the song when his son, steel pan player Freddy Harris III, was born. Ike’s version of the song focuses on the inspirational lyrics, and the arrangement subtly connects to the original through use of steel pan drums.

Taken as a whole, Phoenix is a collection of songs that showcases the stylistic variety of Mojo Ike and Lady Val. The tunes hold together as a unified whole, too.

—Bill Kopp

JEFFREY SCOTT

JEFFREY SCOTT

Going Down to Georgia on a Hog

Music Maker – MM 209

Jeffrey Scott has Piedmont blues in his blood. Despite a working life as a cattleman, gravedigger, hog farmer, and long-haul trucker, he’s never strayed from the musical form he learned from his legendary uncle John Jackson. After years of self-recording and gigging, Scott received assistance from the Music Maker Foundation to record and release Going Down to Georgia on a Hog, a 13-track collection of songs picked up along the way during a nearly 60-year life of singing and playing the blues.

The title track opener offers up a link to Scott’s roots in Piedmont blues. Originally written by Scott’s “Uncle Johnny,” it’s prefaced with a brief explanation as to its meaning. “Hog” is slang for “train,” and the hog is specifically located near the engine. It’s where the hobos who hitched a ride would stay to keep warm while fleeing their troubles in search of a new locale. With its warm performance and focus on escaping the hardships of the past and present in search of a new opportunity, Going Down to Georgia on a Hog serves as nice thematic scene-setter for much of the record.

Songs like Key to the Highway, Freight Train, and Going Back to the Delta all offer different spins on that concept. Freight Train is a particular standout performance. Scott’s vocals are impassioned as he delivers Elizabeth Cotten’s signature tale of the yearning felt with the passing of trains down a railroad track. Key to the Highway is a track Scott learned from his uncle and the straightforward take on the classic tale of getting out of town in the aftermath of a romantic disentanglement serves as a showcase for his deft touch and subtly nimble fretwork as a guitarist.

Going Down to Georgia on a Hog closes with a rendition of Trouble in Mind. The standard is in capable hands with Scott. He perfectly captures the essence of the song, dialing right in on its mixture of weariness and hope. Strumming a simple, steady 12-bar blues, he sings, “Trouble in mind, yes, I’m blue / I have almost lost my mind / But the sun’s gonna shine in my back door someday.” It’s sung from a place of experience that makes credibly performing the song possible, and it makes for a natural conclusion for an album of lived-in, earnestly performed blues.

—Jim Shahen

JABO

JABO

Jabo Blues

Alnico – No #

Known primarily by his nickname, James “Jabo” Houston is one of the mostly unheralded elder statesmen of Austin’s East Side—an historically Black community where blues music flourished long before it regularly graced the city’s more famous entertainment districts. A native of nearby Elgin, Texas, he has been performing the blues for most of his life—both as a musician backing fellow artists such as T.D. Bell, Hosea Hargrove, and others, as well as a bandleader and singer fronting his own group, Jabo & the Old Dogs. This new album, apparently Jabo’s first, is aptly described by its producer and guitarist, Jack Edery, as “a labor of love,” featuring a cast of veteran local musicians covering a repertoire of standards recognizable to most fans of the genre. There’s nothing new or surprising here, just basic comfort food for the ears and soul—as familiar as a plate of chicken-fried steak with white gravy at some downhome Texas diner. Nonetheless, its fundamental blues sound should appeal to folks capable of appreciating honest emotion and raw gumption in the interpretation of well-worn material.

The ten-track set presents a seasoned blues band in all its ragged glory, with Jabo singing lead on six songs and playing organ on four. The somewhat smoother-voiced Roy Crawford contributes lead vocals on three numbers. Though Jabo is rather generously credited as the writer of two of the selections (First Name Is Jabo and Down in Louisiana), they are not actually original compositions, just slightly reworded interpretations of some commonplace blues tropes over well-known tunes. The song menu thus solely comprises staples from the postwar blues canon, including old favorites such as Down Home Blues, Woke Up This Morning, The Things I Use to Do, Night Time Is the Right Time, and so on. Perhaps the least famous among them is [I’ve Got a] Twenty Room House, previously recorded by Bobby Bland during his Malaco years. The disc concludes with the classic instrumental Watermelon Man, on which solid saxophone work (throughout the album) by Bobby Terrell is charmingly supplemented by Billy Cummings on trumpet.

All in all, it’s a nicely recorded, understated production that seems to place the band right there in the listener’s presence—like having the best seat facing a modest stage in some cozy neighborhood bar, a place where the cold domestic beer is reasonably priced and the live music feels like grandma’s kitchen.

—Roger Wood