SHEMEKIA COPELAND

Done Come Too Far

Done Come Too Far

Alligator – AL5010

Done Come Too Far is the third album in Shemekia Copeland’s trilogy that includes America’s Child (2018) and Uncivil War (2020) and melds a signature approach to blues rock and Americana with socially conscious songs that target such issues as racism, gun violence, poverty, and gender discrimination. Essentially, the trilogy is a collaborative effort that melds Copeland’s talents as a singer with material and musical accompaniment tailor-made by producers and songwriters John Hahn and Will Kimbrough. As with the other albums, they recruit a cast of impressive guest stars to help shape their creative vision, including guitarists Sonny Landreth, Kenny Brown, Cedric Burnside, Kevin Gordon, and Oliver Wood; keyboardists Charles Hodges and Pat Sansone; fiddlers Cedric Watson and Fats Kaplin; percussionist Washboard Chaz Leary; and accordion player Andre Michot.

The program kicks off with the hard-edged blues rock of Too Far to Be Gone featuring Landreth’s searing slide work as Copeland boldly salutes heroes from the civil rights movement. Pink Turns to Red features a crunching guitar interplay between Brown, Gordon, and Kimbrough as the singer addresses the horror of gun violence in schools. Memphis soul man Hodges’ B3 provides the underpinning for Copeland’s impassioned delivery of The Talk—the reality check that Black mothers must impart to their children about police violence directed at African Americans. Gullah Geechee is a stripped-down acoustic number that rides on Watson’s African gourd banjo addressing the impulse to survive, resist, and transcend the Middle Passage. Copeland changes pace with Susan Werner’s Why Why Why, a country-inflected love song featuring Sansone’s keyboards and Kimbrough’s strummed acoustic guitar. Leary, Michot, and Watson join the rhythm section on Fried Catfish and Bibles to craft a rocking Cajun/zydeco backdrop for Copeland to celebrate the lives of rural everyday folks. The album’s title track returns to the theme of defiance and determination as Copeland and Burnside intone lyrics that connect the Middle Passage to contemporary struggles while Burnside, Brown, and Kimbrough’s intertwining guitars conjure a swampy groove. Kimbrough’s slide work highlights a bluesy funk take on Ray Wylie Hubbard’s Barefoot in Heaven. They lighten up the mood yet still address America’s racial divide with the slightly tongue-in-cheek country and western of Fell in Love with a Honky. The acoustic guitars of Wood and Kimbrough provide a spare but lilting backup for Copeland’s devastating tale of child abuse on The Dolls Are Sleeping. Hodges’ B3 takes the lead on Dumb It Down, a funky rocker that satirizes misogyny. As she has with the previous two entries in the trilogy, Copeland includes a tune written by her father, Johnny Copeland, Nobody but You, concluding Done Come Too Far with a swaggering blues. Shemekia Copeland has roots that run deep in the blues idiom, and she deserves kudos for working with Kimbrough and Hahn to push the boundaries of subject matter and style to shape an artistic approach that not only entertains but also educates and (hopefully) makes this country a better place for all to live.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

HARRISON KENNEDY

Thanks for Tomorrow

Thanks for Tomorrow

Electro-Fi Records – 3462

In 1967, the hit songwriting team of Holland-Dozier-Holland left Motown to launch their own record labels, Invictus and Hot Wax. The trio assembled a group to serve as a vehicle for their new compositions. That group, the Chairmen of the Board, featured Detroit singers Eddie Custis and Danny Woods plus lead singer Harrison Kennedy, a native of Hamilton, Ontario. Kennedy fronted the group on its biggest hits, including Give Me Just a Little More Time and Everything’s Tuesday, but left the group for a solo career in 1974.

While Kennedy’s bona fides as a soul, funk, and R&B singer were well established, his foundation was always rooted in the blues. That became clearer upon his signing in the 21st century with Toronto-based blues label Electro-Fi. His first release for the label, 2007’s High Country Blues, showcased Kennedy’s style, a heartfelt synthesis of acoustic country blues. The album was nominated at Canada’s annual Juno Awards in the Best Blues Recording category.

Like its predecessor, Kennedy’s 2009 release, One Dog Barkin’, was well-received. Around the time of 2011’s Shame the Devil, Kennedy placed second in the solo/duo competition at the International Blues Challenge. Featuring slide guitarist Colin Linden, Kennedy’s 2014 release, This Is From Here, finally scored him a Juno as well as other awards internationally.

Thanks for Tomorrow is Kennedy’s latest, and finds Linden returning to add his slide guitar stylings to several tracks on the collection of 12 new songs, 11 of which are Kennedy originals. Koko Taylor Award–winner Ruthie Foster joins Harrison for All I Need Is You, the soulful blues duet that opens the album. While the arrangements feature the primarily acoustic foundation that characterizes much of Kennedy’s blues work, there’s cracking electricity in the performances.

There’s a sparking, spirited quality throughout the album, whether on playful tunes like the humorous and self-effacing Easiest Thing, the swaggering blues of On Call Man, or the countrified lover’s ode Women.

Kennedy effortlessly shifts styles between songs, serving up Louisiana-style blues on Checkin’ You Out and interpreting Van Morrison’s soulful balladry on Crazy Love. But the album’s variety is a strength, serving to showcase Kennedy’s mastery and command of the musical landscape.

Kennedy co-produced Thanks for Tomorrow with Jesse O’Brien, a multi-instrumentalist who also provides some of the record’s expressive yet subtle keyboard work. O’Brien shines most brightly on Memphis Trippin’, a hard-edged, smoldering blues in a Muddy Waters vein. That track also features one of Kennedy’s most impassioned vocal performances.

The mood lightens for the fun, up-tempo Cranky Woman. Doomed is characterized in part by some evocative wordless vocalizing; the windswept number has a high lonesome feel, and Kennedy digs into the vocal line, moaning expressively throughout. You Lost Me is a Linden showcase, and features one of the most “electric” arrangements on Thanks for Tomorrow. The record concludes with the spirited jump blues of Just Wanna Play, a perfect and natural set-closer for a superb album.

—Bill Kopp

WALLACE COLEMAN

Folk Blues on Dutch Ground

Folk Blues on Dutch Ground

Ella Mae Music – EMM 3569

You can’t write a review about Wallace Coleman without acknowledging that he is a most refined gentleman, an exceptionally friendly, affable, and kind person, as anyone who has met him will attest. Coleman has a way to bring out the best in people and his fellow musicians. The Cleveland, Ohio, resident was a regular with Robert Lockwood Jr., who held reign at Cleveland’s now defunct club Fat Fish Blue. With Lockwood, Coleman famously developed his rich harmonica sounds, innovating third position harmonica parts that fit perfectly to Lockwood’s jazzy, deep blues amalgam. This writer once lamented that they had more fun in Cleveland on a Wednesday night than we did in New York on a Saturday.

Folk Blues on Dutch Ground is quintessential Wallace Coleman—pure, real blues, down to earth and ethereal. Coleman is an old-school, world-class, deep-roots country blues harp player, second to none. He plays with a warm tone and understated eloquence. As a harmonica player he understands the importance of space, allowing each note room to breathe, with just the right mixture of virtuosity and taste. He can swing over to Chicago style in a heartbeat to swiftly cover the likes of Little Walter, as he does with Juke on this album. Coleman likewise does justice to Willie Dixon’s often-covered Bring It on Home. He is also a fine singer, a true blues, natural, back porch–style tenor with a wide repertoire.

As the title implies, this album was produced in the Netherlands by Robert Slim, along with Coleman and his wife, Jody Getz. Getz also joins as backup singer and acoustic guitarist, and is the featured singer on El Capitan by Peter Chatman. Interestingly, the album features a pick-up band from Holland. Fortunately, the Dutch ensemble knows how to play the blues with a deep groove. Hein Meijer, who inexplicably calls himself by the silly stage name Little Boogie Boy, shines like a diamond on lead electric guitar and as bandleader. Jan den Boer is a fine contrabass player and Bert Fonderie holds down the beat on the drums. John Lucic completes the sound on electric guitar.

The disc has a gentle, unpretentious vibe through its 12 songs. They were having fun playing and that comes across. Coleman keeps it smooth and mellow, grounded all the way through. Nobody is showing off here. It’s all about the overall sound, comfortable and accessible, clean, yet impassioned. Coleman plays straight harp on the most unusual, and also the sweetest cut on this album, Irving Louis Burgie’s Jamaica Farewell. That song is in the style of mento, a traditional Jamaican folk music style, and was made famous by Harry Belafonte, among others. They also do a nice version of Make Me a Pallet on the Floor. Coleman shows his subtle chops on Sonny Boy Williamson II’s Mighty Long Time, which is one of three songs recorded in the Uncle Larson Studio in the Hague, Netherlands, along with Bring It on Home and Memphis Minnie’s What’s the Matter With the Mill. All other songs were recorded live at Paco Plumtrek in Almelo.

Folk Blues on Dutch Ground is another feather in Wallace Coleman’s cap, fun from start to end.

—Frank Matheis

KAT RIGGINS

Progeny

Progeny

Gulf Coast Records – No #

The gifted vocalist and songwriter returns with another set that melds personal, spiritual, and social themes (struggle, uplift, victory, hope), all held together by her lyric acumen, her focused and emotionally explosive vocals, and the hard-charging yet clean and precision-honed backing of her studio band.

Riggins’ singing can be as rough-edged and caustic as that of any blues singer, but she can also summon a rich croon that often, as in the neo-apocalyptic Sinkin’ Low, she imbues with a bitterly ironic tenderness. Her phrasing incorporates strong influences adapted from rock, pop, and hip-hop as well as more “traditional” soul and blues. It might also be noted—although, by rights, it shouldn’t even have to matter—that her protagonists feel free to proclaim their erotic desire for women (e.g., Espresso) unselfconsciously and fearlessly, carrying on a tradition extending at least as far back as Lucille Bogan and Ma Rainey (although, as befitting their times, both Bogan and Rainey apparently felt compelled to couch their same-sex eroticism in irony and hard-bitten humor—Riggins sings straight ahead).

In several places, Riggins has invited guests (one is almost tempted to call them “fellow travelers”) to spice things up even more. Woahman, a tough-love admonition to girls and women to rise up and assert themselves (“You belong here, you were taught to find your voice / and if they ain’t tryin’ to hear it / Well then you don’t give them that choice”), features some explosive guitar work from Chicago’s Melody Angel (a soulmate of Riggins’ if there ever was one); My City, a hard-bitten and heartfelt love song to Riggins’ native Miami, finds rapper Busta Free and rock-powered guitarist Albert Castiglia bringing additional stylistic/genre-melding brio to the mix.

Kat Riggins is one of the most eloquent and exciting “new” voices in contemporary blues, and this latest project showcases her at the height of her powers.

—David Whiteis

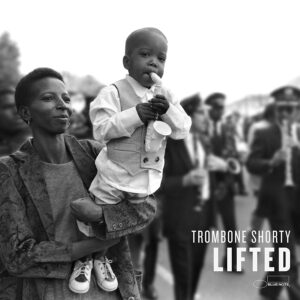

TROMBONE SHORTY

Lifted

Lifted

Blue Note Records – B0034569-02

Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews has bona fide roots in the second line brass band and funk traditions of the Tremé neighborhood in New Orleans. Family is essential to maintaining and extending the city’s cultural and artistic heritage, and this is certainly true for the trombonist/trumpeter/vocalist. He’s the grandson of the legendary R&B singer Jessie “Ooh Ooh Pah Doo” Hill; his older brother James Andrews is a highly regarded traditional jazz trumpeter and singer, and his cousin, Glen David Andrews, is also a trombonist/singer who is a fixture on the city’s music scene. By age four, Shorty was sitting in with Bo Diddley at Jazz Fest and was leading his own brass band just a couple of year later. He attended the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts (NOCCA) with Jon Batiste, and like the singer/keyboard player his career has taken off, garnering worldwide recognition. Lifted, his fifth album on a major label and first in five years, pays homage to his mother, Lois Nelson Andrews. As he explains: “She passed recently, but she continued to inspire me right up until she transitioned, and that’s why I put a picture of her holding me up at a second line on the cover of this album. She lifted me up my whole life.”

Lifted seems to be crafted to push Shorty further into the contemporary pop music pantheon. The New Orleans roots are there, but they’re immersed in a big-time produced sound that calls to mind master pop craftsmen like Paul McCartney or Michael Jackson, rather than the low-down, primal grooves of the Meters or the Dirty Dozen. There’s a lot of ear candy going on here, especially with the intricate vocal arrangements. Every track features a level ten intensity, so they aren’t that distinguishable. Shorty delivers fiery trombone and trumpet solos throughout the album, but they’re immersed in this soundscape he’s crafted. The same can be said for guest Gary Clark Jr.’s slashing guitar solo on I’m Standing Here. The two tracks that have the most identifiable New Orleans flavor are Everybody in the World and Miss Beautiful. The former features the New Breed Brass Band and opens with some flag-waving big band swing, locks into a funk groove, and morphs into a hip-hop segment featuring Shorty’s rapping. The latter is the album’s highlight with New Breed snare drummer Jenard Andrews (Shorty’s nephew) engaged in a syncopated, polyrhythmic dialogue with set drummer Alvin Ford Jr. (who stands out throughout the album). It’s hard to deny the heights to which Trombone Shorty has risen in today’s pop music scene. Hopefully, he’ll keep in mind that a century earlier Louis Armstrong attained superstardom rooted in the same musical heritage, but he always made it clear he knew what it meant to miss New Orleans.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

DYLAN TRIPLETT

Who Is He?

Who Is He?

VizzTone – No #

This would appear to be the first recording of 21-year-old, St. Louis–based vocalist Dylan Triplett. His setlist is unusually imaginative for such a young artist—the fare includes an adaptation of a Paul Laurence Dunbar poem (Barnyard Blues), an inspirational Bill Withers classic (the title tune), and a remake of the jazz standard All Blues, featuring the original lyrics by the late Oscar Brown Jr., who recorded it in 1963, four years after Miles Davis’ iconic version, as well as a couple of originals.

Triplett’s bio credits him with a vocal range of over four octaves; apart from that, he’s also a versatile stylist, comfortable with grit-inflected, bluesy testifying (Lonnie Brooks’ Feels Good Doin’ Bad, Junkyard Dog, the aforementioned Dunbar adaptation), emotionally resonant balladry (the brooding, pop jazz–flavored Brand New Day, Same Old Blues, the Withers remake, and his own swamp gospel–tinged I’ll Be There Waiting), among other embellishments and variations on the “pure” blues form.

In some ways, and probably to be expected, Triplett sounds as if he’s still a work in progress. His phrasing sounds uneasy in places; it was admirable for him to take on the Davis/Brown classic (and Joe Sublett’s funk jazz arrangement lets us hear it with new ears), but he can’t seem to find the vocal sureness to negotiate the melody line without sounding mannered. On the other hand, he brings a world-toughened resolve to the Isleys’ That’s the Way Love Is, and on a dark-night-of-the-soul meditation like Brand New Day, Same Old Blues, he effectively inhabits the persona of a scarred life traveler who sounds, at least, as if he’s considerably older (and wearier) than Triplett himself.

This sounds like the debut of a voice with the potential to make a significant contribution to the blues world in coming years.

—David Whiteis

WALTER TROUT

Ride

Ride

Provogue – PRO76772

Despite a career that stretches back more than 40 years and includes notable roles as lead guitarist for such distinguished and distinctive outfits as Canned Heat and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Walter Trout never fully avoided the trials and tribulations that often accompany stardom. As many artists will admit, the temptations that they encounter can create unimagined situations. Trout’s struggle with alcohol abuse, cirrhosis and, in its aftermath, the debilitating brain damage that left him unable to speak, play guitar, and nearly wholly immobile has been well documented, but remarkably, he made a full recovery thanks to a liver transplant paid for through fundraising and the support of his devoted fans. Now, eight years later, at age 71, he’s not only back at the top of his game, but the recent recipient of practically every imaginable award bequeathed in the blues idiom.

Nevertheless, Trout hasn’t forgotten the lessons learned from those perilous circumstances nor from a childhood fraught with anxiety and despair. With his revelatory new album, Ride, he confronts that past and offers insight into how he was bravely able to move forward. “Some folks tell me I’m a wise man, some folks tell me I’m a fool,” he declares on the tellingly titled So Many Sad Goodbyes, one of many stand-out selections shared here. That said, there’s nothing particularly conciliatory about this set of songs. The outspoken anthem High Is Low combines grief with gravitas, but even so, remorse and resignation generally give way to determination and defiance. Even when he concedes a feeling of hopelessness and despair (“Ain’t nothing’ movin’ / It’s so hard for me to carry on”) on the tattered ballad Waiting for the Dawn, one gets the feeling he’ll somehow find the resolve to do exactly what he needs to. The fact that it’s followed by a decided call to action, the stinging and surging Better Days Ahead, makes that all the more apparent.

Naturally, that’s owed to Trout’s stinging vocals and scorching guitar riffs, abject expressions of the skill, and savvy that have elevated him into the highest tiers of today’s most celebrated superstars. However, credit is also due to his able ensemble—Teddy Andreadis on piano and Hammond organ, bassist Jamie Hunting, drummer Michael Leasure, and veteran producer Eric Corne. They imbue the added urgency, reinforcing the profound drama and dynamic that surges through each of these offerings. That’s especially evident on the power ballad The Fertile Soil, the driving and dynamic I Worry too Much, and the rollicking and decisive Leave It All Behind.

Ultimately, Ride comes across as a revelatory endeavor, one that further affirms Trout as one of the most articulate and energetic proponents of contemporary blues on the scene today. With Ride, that remarkable journey continues.

—Lee Zimmerman

SILENT PARTNERS

Changing Times

Changing Times

Little Village – LVF 1051

The stirring, evocative strings that adorn Ain’t No Right Way to Do Wrong, the opening track on Silent Partners’ debut album, Changing Times, serves notice that the group is no rote blues trio. With a feel that hearkens back to classic soul sides of the ’70s, the tune is a slow burn that establishes the group’s complete mastery.

Silent Partners is a three-piece featuring studio and performance veterans Tony Coleman (drums), Jonathan Ellison (guitar), and bassist Russell Jackson. It’s one of many components of the trio’s strengths that all three men are accomplished vocalists as well. Collectively and individually, the three musicians have credits that include work with Bobby Bland, B.B. King, Denise LaSalle, and Johnnie Taylor.

Backed by ace session colleagues producer Jim Pugh on keys, guitarist/engineer Kid Andersen, Linda Leuschner Andersen on soulful backing vocals, and other select players, Silent Partners serve up a peerless set of ten tracks. Searing guitar licks and propulsive bass work take an otherwise unassuming blues number like Post Traumatic Blues Syndrome to someplace special.

Drummer Coleman does an impressive B.B. King vocal impression on the good-natured Never Make Your Move Too Soon; appropriately enough, the song tells the story of how he came to work with King in Chicago. The group shifts into high gear for the rollicking Dancin’ Shoes, a showcase for Ellison’s lean and mean lead guitar in an Albert Collins vein. The whole album has a tight and energetic yet relaxed vibe that suggests how the band might sound live onstage, but it’s a safe bet that tunes like Dancin’ Shoes would take even higher flight on the bandstand.

The swaying Love Affair with the Blues splits the difference between supercharged Chicago blues and the kind of blues rock epitomized in the late ’60 by Jimi Hendrix. Well-placed bursts of lead guitar offer a tasty contrast with the song’s quieter moments. Proving Ground is a funkified workout that underscores the versatility of this outfit. It also demonstrates that a song need not have a bunch of chords to be effective (this one rarely ventures beyond two of ’em).

The smoky, assured Teasing Woman features some especially beefy bass work from Jackson. The song’s economical arrangement keeps the focus where it belongs: on the three core instruments and the peerless vocal. Good to Myself is classic guitar-led blues, with a wonderfully extended instrumental intro, some inventive changes, and a spirited outro.

Silent Partners wrap with Beale Street Shuffle, a loping tune that has it both ways: it pays tribute to the urban blues that have come before and provided a solid foundation, while looking toward the future. And with a debut like Changing Times under their belt, the future looks bright indeed for Silent Partners.

—Bill Kopp

ALBERT COLLINS & THE ICEBREAKERS

At Onkel Pö’s Carnegie Hall

At Onkel Pö’s Carnegie Hall

Jazzline – N 77040

For many of us, the Holy Trinity of Texas blues guitarists comprises Blind Lemon Jefferson, T-Bone Walker, and Lightnin’ Hopkins—key innovators born between 1893 and 1912. But among the next generation of players directly inspired by any of those Prime Movers, the idiosyncratic genius of Albert Collins stands out. Born in 1932 in rural Leon County, he came of age in Houston’s Third Ward, a district then burgeoning with great guitar players. But unlike the others, Collins utilized an unusual alternate tuning, down-the-neck capo placement, and a precisely aggressive picking style to create his own sound. That versatile sonic signature, along with Collins’ improvisational brilliance as an instrumentalist and capability as a vocalist, informed a recording career that launched in the late 1950s and encompassed some of the most essential blues albums of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. Since his death in 1993, Collins’ legacy has thrived on the vitality of those original studio tracks or various concert performance recordings. Released recently as part of an archival series from a European music venue, this latest live album presents the mature Collins at the height of his powers—artistically speaking, still in his prime.

Recorded in December 1980 at a mid-sized nightclub in Hamburg, Germany, that one-night concert comprised two sets, documented here in their entirety—replete with on-stage introductions and brief commentary between some songs—over the course of two CDs. Each set begins with four numbers performed by Collins’ hot-shot touring band, the Icebreakers, featuring A.C. Reed on tenor sax and vocals, Marvin Jackson (mislabeled in the notes as “Jackson Marvin”) on second guitar, Johnny B. Gayden on bass, and Casey Jones on drums and vocals. Collins exercises his vivid musical imagination and fretboard prowess on a total of 11 tracks, including several long jams.

Following the proficient warm-up segments by the Icebreakers, the sets really take off, as expected, when “the Master of the Telecaster” is called on stage. As the band churns with frenetic energy, Collins’ distinctive guitar licks on Listen Here first confirm his presence before he addresses the audience and then immediately generates a magnificent solo. The subsequent number, I Got a Mind to Travel, reveals Collins’ proficiency at interpreting a slow blues—especially on the plaintive, highly emotive string-stretching solo, which triggers an enormous response from the crowd. The vibe shifts again to upbeat with the sprightly instrumental Frosty. Then it decelerates gracefully with Cold, Cold Feeling, a T-Bone Walker standard. This track is arguably the highlight of the first set, especially gauging by the enthusiastic response from beyond the stage. The nimble instrumental Ice Pick kicks in next. Supplemented by an extended sax solo by Reed, Collins stretches the vibrant number into an almost 16-minute improvisation before a big ending.

Following another solid opening sequence by the Icebreakers, Disc Two hits its first transcendent moment on the well-worn cover song Mustang Sally. As the band lays down the rhythmic foundation, the sudden presence of that icy tone signals that Collins is reinventing this overly familiar number as a sonically adventurous and wide-ranging instrumental. Amid the solos, there’s some fantastic interplay too between Collins and Reed. On the subsequent treatment of Things I Used to Do, Collins’ raspy and fervent vocal delivery reminds us that for all his talents on guitar, he could also vocalize expressively. Collins sings again on the jumping shuffle Caledonia, but the ear-opening action truly transpires in those ice-picking solos. And on Conversations with Collins he makes the instrument seem to speak, interrogate, scream, whisper, beg, and otherwise communicate the dialogue of a comedic inter-spousal confrontation. The closing track, Cold Cuts, is perhaps the best exemplar of what this live recording offers—not just faithful recitations of rehearsed material but freeform music-making in the spirit of jazz. It opens with a supremely funky bass workout by Gayden before the others join in. This amalgam amazes with its constantly evolving musical conversation. In due time Collins interjects his own inspired response, summoning new sounds, textures, and tones from his guitar on a track that runs for almost 20 minutes.

This audio documentary transports the listener through time and space to Hamburg’s Onkel Pö to experience a complete concert performance—from the preliminary set-openers by the Icebreakers to the Collins-centric climaxes. Featuring one of the most ingenious blues guitarists of all time, that’s a trip well worth taking.

—Roger Wood

AL BASILE

Through with Cool

Through with Cool

Kenoza – 9946

Al Basile originally earned his rep as a horn player in Roomful of Blues a half century ago. And the idea of a cornet-based blues is an intriguing one. Lead cornet or trumpet is not unheard of in the blues (Derrick Shezbie of New Orleans comes to mind), but it remains an outlier compared to the prominence even of tenor sax players in a musical landscape dominated by the guitar.

But like Louis Armstrong (long) before him, Basile has found greater fame as a singer—and the reality is that his latest album, Through with Cool, is much more drenched in the guitar of Kid Andersen and organ of Bruce Bears than it is in Basile’s trumpet. As with fellow trumpeter Herb Alpert’s ’80s synth pop dance hits, Basile reserves his horn here for well-placed punctuation and the occasional solo.

And those cornet solos are very much blues-drenched, albeit from the jazz side of things. Some listeners are going to wish there were more of them—and not due to any deficiency in Basile’s singing, nor his band’s overall playing. But his horn playing is so unique that the small snippets we get only whet our thirst. The closest we come to getting that thirst slaked is a lengthy solo toward the end of Not Anyplace at All, where he reinvents the melody a half dozen different ways over a percolating groove from the band. The muted solo on Couldn’t Live with It is another gem.

His singing is in the vein of Willie Nelson or Charlie Musselwhite—a physically limited voice somehow reveals the emotional power of his delivery.

That emotional punch likely results in large part from the fact that Basile—a published, highly regarded poet—wrote all the music and lyrics here, as well. The tunes range from basic shuffles (Uh Huh) to R&B (We Belong Together), and West Coast blues (My Hero) to acoustic country blues (Through with Cool).

Tying them all together are Basile’s world-weary yet warmhearted lyrics—tales told from the point of view of a man in his 70s, still moving forward but not afraid to look back and try to figure out what he’s learned along the way, or what he should have learned, anyway.

A fine, representative sample comes from My Hero:

“‘My hero’ is what she says when she asks you to save her

‘My hero’—you know the sound sounded good to me

But the costume’s loose and the cape don’t fit

I don’t know how to fly, that’s the truth of it

Her hero is something I can never be”

—Jim Trageser