LITTLE FREDDIE KING

Going Upstairs

Going Upstairs

Newvelle Records – NVN002

Initially released as part of Newvelle Records’ The New Orleans Collection box set that also includes LPs by singer Irma Thomas, pianist/singer Jon Cleary, and pianist Ellis Marsalis for his final recording session (accompanied by his son, vibraphonist/drummer Jason), Going Upstairs just might be the best recording ever made by guitarist and singer Little Freddie King. His recent albums have featured him in a range of settings, from At Home in the New Orleans Musician’s Village (2015), an informal living room jam session with Music Maker Relief Foundation President Tim Duffy on second guitar, to You Make My Night (2017), a raucous live set recorded at d.b.a. music club on Frenchmen Street, to Jaw Jackin’ Blues (2020), a mashup of King’s storytelling and playing looped over pulsing electronic beats and wailing background vocals. One of the things that distinguishes Going Upstairs is the pristine sound quality of the clear vinyl LP that can likely be attributed to the work of Esplanade Studios owner and engineer Misha Kachkachishvili (the title track was recorded live at BJ’s Lounge). The other distinguishing factor is that King is laser-focused on crafting the performances of these ten tracks in a stripped-down setting. King is joined by various combinations of “Wacko” Wade Wright on drums and tambourine, Paul Defiglia on bass, and Stephen Daly on second and slide guitar.

These performances bring to mind the early 1960s recordings of both John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins playing country blues on their electric guitars, occasionally working with rhythm sections. Opening the program with the instrumental Bywater Crawl, King channels Hooker with a driving, foreboding boogie, and the live track, a Hooker composition that closes the LP’s second side, definitely elevates the energy level as the singer/guitarist is wont to do. In between those two numbers, King spars with Daly’s stinging slide guitar riffs on the understated Pocket Full of Money. He flashes some hot licks in a trio format on the slow blues Going Up the Mountain. Guest harmonica player Robert Louis diTullio Jr. helps King push the groove on I Used to Be Down. Hopkins’ legacy looms large over two numbers: Bus Station and Can’t Do Nothing Baby, the former slow and pensive and the latter a loping, infectious groove. Standing at Your Door, with guest pianist Elan Mehler, gives King a chance to swagger. It sounds like he pulls out an acoustic guitar for Coming Home to Jesus, and Mean Little Woman spotlights King’s solo guitar work. Going Upstairs is a definitive showcase that allows the nuances of Little Freddie King’s singing and guitar playing to shine brightly through.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

GUY DAVIS

Be Ready When I Call

Be Ready When I Call

MC Records – MC-0088

Be Ready When I Call is Davis’ third album for MC Records, the vibrant New York roots and blues label. It’s again a New York affair: Guy Davis hails from Harlem and now lives in the Bronx. Davis carries lead vocals, acoustic guitars, banjos, harmonicas, and tambourine. The musicians, his regular crew, are among the very finest on the Hudson Valley Woodstock scene: Professor Louie (Aaron Hurwitz) plays keyboards; Gary Burke on drums; John Platania on electric and acoustic guitars; Mark Murphy on contrabass and cello. Christopher James joins on two cuts on acoustic guitar, banjo, and mandolin.

Guy Davis is a musician, composer, actor, director, and writer, one of New York’s significant roots and blues players. On this album he manifests a clear sociopolitical theme, which is not surprising given his heritage and influence. His famous parents, actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, were both important civil rights activists. Pete and Toshi Seeger were close family friends. Guy Davis has always stood up for what was right. The prolific Davis sings out boldly and unequivocally with righteous indignation. Be Ready When I Call may be his most poignant message ever. He has something powerful to say and lays it down just right, with superb instrumentation, great songs, and a cool vibe. He is sociocritical without being overtly preachy, but, well, he surely kicks ass on this one.

The stunner on this record is God’s Gonna Make Things Over, a song that takes on the 1921 Tulsa race massacre (also known as the Tulsa race riot), when a white mob burned down the African American neighborhood of Greenwood, displacing thousands and killing hundreds. Davis sings: “Though my people may be slaves buried down in nameless graves / God’s gonna make things over one of these days / Tulsa Oklahoma,1921 / That’s when the killing had just begun. / God’s gonna make things over one of these days / It ain’t right! . . . It ain’t right! . . . / What the white folks did in Tulsa on that night.”

And, “Tell me what did you learn / When you watched my body burn? / When you hang me from a tree / Raise me high so my people see.”

Flint River Blues takes on the well-publicized lead poisoning of the city’s water supply. Davis sings, “If you hear this song DON’T DRINK THE WATER!” Even the difficult topic in the Middle East is tackled on Palestine, Oh Palestine. On I’ve looked Around, he takes on the plight of refugees: “I’ve seen people walk a thousand miles. / For asylum through a gate. / Risking jail and deportation / To stand and beg and wait. / The guards took a baby / From a nursing mother’s breast. / America is great / But this cannot be her best.”

He closes the album with a departing knock-out punch to Donald Trump on the funky-rocking rap Welcome to My World: “Stormy Daniels got you laid / Michael Cohen got you paid / Saudis got a bone saw blade / But you’ve got no soul left to trade for your misbehavior.”

The refrain of that song summarizes the outrage in this powerful album: “NO MORE! NO MORE! NO MORE! NO MORE!”

Guy Davis and many other African American musicians are saying loudly what needs to be said! It all fits as Davis expresses fury with finely crafted songs.

—Frank Matheis

MARIA MULDAUR

Let’s Get Happy Together

Let’s Get Happy Together

Stony Plain – SPCD 1420

Talk about a kismet—a few years back, Maria Muldaur was shopping in a Woodstock clothing store and was taken by the swing music that was playing. She assumed it was vintage recordings being broadcast on a local radio station and was stunned to hear it was a recent recording by Tuba Skinny, a band of buskers who, beginning in the early 2000s, have enlivened the streets of New Orleans and gone on to perform at festivals around the world. Muldaur eventually got a selection of the band’s recording, and a fan was born. She met and sat in with the band in 2018 when she was in New Orleans to record her last album, Don’t You Feel My Leg: The Naughty Bawdy Blues of Blue Lu Barker. Last year, Muldaur was back in the Crescent City for a showcase at the Folk Alliance International, and she asked Tuba Skinny to back her up. The performance prompted an offer to make a record. That’s the genesis of Let’s Get Happy Together.

The agenda here is all swing, all the time. The band, which works regularly, is super tight, and the recorded sound is clear and immediate. The drive of the rhythm section is unrelenting, and the horn players push the groove with infectious riffs and individually deliver concise and inventive solos. For Tuba Skinny, generating the uplifting energy of swing is a communal project. Muldaur clearly relishes the support they provide, and her voice—with that trademark seductive burr—is in spectacular shape.

Muldaur did some deep research and put together a program of a dozen fairly obscure tunes from the 1920s–1930s heyday of swing music. Highlights include the title track from pianist (and second wife of Louis Armstrong) Lil Hardin Armstrong; two finely crafted songs from the woefully underrecognized trumpet virtuoso Valaida Snow; the bluesy Delta Bound, originally recorded by Ivy Anderson with Duke Ellington; a Billie Holiday / Lester Young–inspired version of Irving Berlin’s wry He Ain’t Got Rhythm; two hits, Be Your Natural Self and Some Sweet Day, from Frankie “Half Pint” Jaxon, another underrecognized singer who was a big star back in the day; and the rollicking blues-inflected Road of Stone from Addie “Sweet Peas” Spivey, younger sister of classic blues diva Victoria Spivey, who was Muldaur’s original mentor during the folk revival in the early 1960s. If there’s validity in Ellington’s maxim “It don’t mean a thing, if you ain’t got that swing,” then there’s a whole lot of meaning in Maria Muldaur’s Let’s Get Happy Together.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

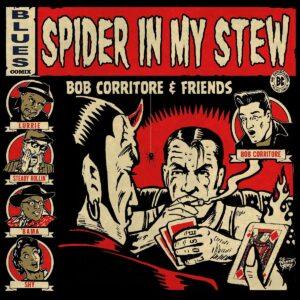

BOB CORRITORE & FRIENDS

Spider in My Stew

Spider in My Stew

SWMAF Records – SWMAF18

On Spider in My Stew by Bob Corritore & Friends, the emphasis is rightly placed on the “and friends” component.

Corritore, the Phoenix blues harp savant, producer, radio DJ, and owner of the famed Phoenix blues club, the Rhythm Room, has a lot of friends—so many that his Rolodex must be housed in its own room (trust me, youngsters, the Rolodex really did exist at one time). Each of the 38 musicians appearing on the album’s 14 tracks bring their own special flavorings to this blues stew.

This isn’t the first time Corritore has called on his litany of musical friends to produce a sterling blues release—the most recent example being 2019’s excellent Do the Hip-Shake Baby!. The recipe remains intact: pick some cool and eclectic covers and a handful of originals, give them some inventive arrangements spiced with Corritore’s harp serving as the roux, and let the players play and the singers sing.

For a guy who wears a closet full of musical hats, Corritore has been a pretty relentless recording artist since releasing his first album in 1999. Here he shares producing credits with Clarke Rigsby on the album derived from nine sessions between 2018 and 2020. Frequent collaborators like Alabama Mike, John Primer, Willie Buck, and Sugaray Rayford are in the mix again in a lineup that includes ten vocalists.

The tracks run the gamut from energetic shuffles to mid-tempo stomps to gutbucket slow-burners. Oscar Wilson lends his smooth pipes to the swinging opener, Tennessee Woman. Rayford brings his rough and tumble vocals to his composition Big Mama’s Soul Food, an homage to “neck bones, oxtails, butter beans, and fried baloney.”

Diunna Greenleaf channels Koko Taylor, while Corritore conjures upper register playfulness and Fred Kaplan’s piano flows like water on Don’t Mess with the Messer. Singer/guitarist Lurrie Bell envelopes the title track—an old Willie Dixon tune—while Bob Margolin serves up soulful guitar and Bell adds his own South Side–inspired licks. Why Am I Treated So Bad features a sly arrangement, some of Corritore’s best harp, and languid guitar by Kid Ramos and Johnny Main, all topped by Francine Reed’s so-honest-it-hurts vocals.

Jimi “Primetime” Smith serves up some crisp, B.B. King–like fills as Johnny Rawls wraps his rich baritone around his own Sleeping with the Blues. Willie Buck testifies on the gutbucket Soon Forgotten as Corritore cooks up a sizzling solo.

Margolin returns to back Bell on the singer’s I Can’t Shake This Feeling, a tight shuffle bolstered by a wonderful arrangement with the rhythm guitar doubling Troy Sandow’s liquid bass line. Look Out borrows liberally from the chord pattern of the classic Motown hit Money, but Alabama Mike makes it his own with his playful vocals.

The sorrowful cover of Dylan’s I Shall Be Released—covered famously by the Band—finds Reed backed by brother Michael Reed on vocals on this superb closer.

Corritore has carved out a niche as a maestro of pure, unfiltered blues, and Spider in My Stew finds this master collaborator and cohorts in fine form.

—Rod Evans

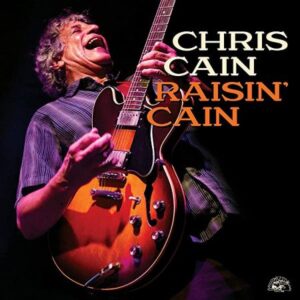

CHRIS CAIN

Raisin’ Cain

Raisin’ Cain

Alligator – ALCD 5003

Though he’s a white musician based in San Jose, California, Chris Cain’s vocal and guitar styles owe a significant debt to B.B. King. As showcased on Raisin’ Cain, his first album for Alligator Records, Cain’s approach to the blues is one steeped in the postwar electric tradition.

Lyrically, Raisin’ Cain traffics in familiar blues territory, with street-level stories and sentiments that connect with listeners without pandering or cliché. Cain’s expressive voice—with phrasing influenced by Ray Charles and delivery informed by B.B.—is the vehicle to put his lyrical ideas across. And Cain’s lean, powerful lead guitar lines are melodic in the extreme, propelling the songs forward rather than overwhelming them with showiness.

Raisin’ Cain follows on with key elements that made his self-titled 2017 album (released by the Little Village Foundation) so successful. Producer and fellow guitarist Kid Andersen led the sessions at Greaseland Studios. The arrangements across the album are varied: half the numbers feature a four-piece horn section led by Michael Peloquin.

Cain’s recorded debut was 1987’s Late Night City Blues; he’d go on to release three records for Blind Pig, and made several more for his first label (Patrick Ford’s Blue Rock’it) and self-released a few as well. As Dick Shurman notes in Raisin’ Cain’s liner note essay, the guitarist tried years ago to get onto Alligator, but they passed. In 2021, however, he seems right at home on Bruce Iglauer’s label.

Cain knows his way around electric blues. I Don’t Know Exactly What’s Wrong with My Baby sounds like a lost B.B. King track, and his Albert King–flavored extended lead on the big band backing of Out of My Head is the icing on a very tasty cake.

The most unusual cut on the album is the last one. For Space Force, Cain puts down his electric guitar and steps up to an Arp Soloist, a vintage synthesizer that ceased production in 1977. The compact monophonic (one note at a time) keyboard has a distinctive sound all its own, and Cain smoothly integrates the instrument into a playful, up-tempo blues arrangement. Here he’s channeling George Duke or Stevie Wonder more than the three Kings, but Space Force makes a credible argument for the synthesizer as a credible conduit for the blues. The tune has more traditional elements, too: Andersen takes a brief melodica solo, and keyboardist Greg Rahn—who excels throughout the record—turns in some nice organ washes and a tasty electric piano solo.

The appealing if atypical Space Force aside, Raisin’ Cain keeps its focus squarely on good-timing, catchy blues, played with feeling, finesse, and conviction. It’s sincere without being insular, expertly produced but not slick, and true to the spirit of blues without being imitative. Fifteen albums in and at age 65, Chris Cain is turning out the best work of his career.

—Bill Kopp

DUMPSTAPHUNK

Where Do We Go from Here

Where Do We Go from Here

Provogue – TFG 76302

Dumpstaphunk’s first new album in seven years Where Do We Go from Here moves in two directions. It reaches back to the past to the foundations of funk in the early 1970s, and it recasts those roots with a dynamic, contemporary sound that paves the way for the future of the music. Formed in 2003 by singer/keyboardist Ivan Neville to back him up for a solo performance at the Jazz and Heritage Festival, the band still features cousin Ian Neville on guitar and the unique tandem of two bass players, Tony Hall and Nick Daniels III, who also share the lead vocal duties. The band’s drum chair has been anchored by the groove mastery of Raymond Weber, Sr., Nikki Glaspie, and Alvin Ford, Jr. (who plays on many of the tracks here). Current drummer Devin Trusclair certainly carries on that rhythmic legacy. In recent years the lineup was expanded to include trumpeter Ryan Nyther and trombonist Alex Wasliy. Together, they generate distinctive powerhouse, low-end-dominated funk grooves that absolutely compel movement.

The 11-track program pays homage to the maestros who initially shaped the funk approach to rhythm and blues. The opening track United Nations Stomp instantly conjures the Band of Gypsys, so there’s no surprise that it’s a cover of an early 1970s Buddy Miles composition. Blues rock guitar slinger Marcus King guests to play the role of a latter-day Jimi Hendrix. Tracks like Make it After All and Where Do We Go from Here pay homage to bands like Rufus and War. Sly Stone’s influence is exhibited in the motion-inducing cover of his In Time, which appears on his album Fresh (1973). The ultimate funk source point, Soul Brother #1 James Brown, has got to be in the mix, and it’s easy to imagine Brown working out over the percolating groove set by the interweaving lines of the horns and rhythm section on the instrumental Dumpstamental. Of course, Dumpstaphunk is a New Orleans band that’s integrally linked to The Meters/Neville Brothers, and they clearly extend that legacy of tracks like the cover of the late Gerald Tillman’s mid-seventies gem Let’s Get At It; Backwash with its sassy Allen Toussaint–inspired horn arrangement and surging organ that channels Art Neville’s work with the Meters; and Do You, that conjures the soulful vocals of Cyril Neville. The band pulls in other influences such as the punchy horn parts exhibiting a Dirty Dozen Brass Band influence fused to the churning drive of Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters. Justice 2020 is one final highlight that includes the three singers trading verses and a guest rap that acknowledges last year’s Black Lives Matter protests. Although Dumpstaphunk has solid jam band credentials, Where Do We Go from Here is a far cry from a band cutting loose in the studio. It’s a sophisticated, polished production dedicated to generating funk that will insist that listeners get up on their feet and groove.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

WILLIE CLAYTON

Ultimate Willie Clayton

Ultimate Willie Clayton

Mardi Gras – MG 1131

Southern soul blues superstar Willie Clayton has amassed one of his genre’s most formidable recorded catalogs, dating back to his mid-1970s debut on the Pawn label, a subsidiary of Hi. This time out, he reprises some of his best-known hits—I Love Me Some You, Three People (Sleeping in My Bed), Equal Opportunity, and several others—with newly recorded versions that nonetheless hew pretty closely to the originals, the primary difference in most cases being the studio backing, which tends to be a bit more sparse this time out. (On Equal Opportunity, the role of the wronged paramour getting her just deserts, sung by the late Pat Brown on the 1993 original, is filled capably by Vickie Baker.)

As is often the case with Mardi Gras, the production here is somewhat muted—especially noticeable on some of the remakes, which lack the high-end crispness that characterized the original versions. In addition, the track numbering is a little confusing—what’s written on the sleeve doesn’t correspond exactly with what’s on the disc. Clayton, though, comes through strongly. At age 66, he doesn’t seem to have lost any of his vocal suppleness, resonance, or emotional depth; he can plead, scold, cajole, and seduce with equal aplomb. No songwriting credits are provided, but Clayton and/or his team at Mardi Gras have recruited first-rate tunesmiths, following honorably in the steps of such ace craftsmen as the late Bob Jones, who penned Equal Opportunity, among others, for Clayton before his own demise in 2016.

There’s plenty of booty-shaking, backdoor-love fun to be had here—Drop Pop and Roll; Can We Slip Away; and remakes of Ronnie Lovejoy’s Sho Wasn’t Me, Mel Waiters’ Hole in the Wall, and Gwen McCrae’s Rocking Chair are just a few examples—but true to the deep-soul heritage he venerates, Clayton is most effective at portraying a passionate, erotically charged alpha male who is nonetheless vulnerable. In Love Don’t Hurt Me, the wounded warrior dares to re-open his heart; Sidepiece on the Side, despite the sexual swagger implied by the title, finds the would-be Lothario out-Jodied by the woman he’s ostensibly cheating on. I’d Rather Go Blind, perhaps the sleeper of the set, is Clayton at his most soulful, daring to fully inhabit a song that up to now has been almost exclusively associated with women—Etta James, of course, as well as various others who have covered it through the years.

“I am rhythm and blues, and I’m still standing tall,” Clayton sang in 2012, in another song written for him by Bob Jones. It might have been a bold claim to make, but he’s lived up to it. Judging from this outing, he seems determined to keep doing so.

—David Whiteis

ELIZABETH KING

Living in the Last Days

Living in the Last Days

Bible & Tire Recording Company – BTRC011

Sometimes an album opens with a song that lifts us so high that we feel as if we have been redeemed and transported momentarily to another plane, and we wonder if the rest of the album can carry us to the heights of that opening song. No Ways Tired, the first track on Elizabeth King’s new album, her first in 45 years, begins sparely with her vocals floating over Mark Stuart’s thumping bass before taking off into a sonic stratosphere, driven by Will Sexton’s and Matt Ross-Spang’s crunchy Memphis soul guitars, spiraling higher and higher with backing vocals by the Vaughan Sisters and the D-Vine Spiritualettes. King’s energy, determination, and confidence shine brightly, and the song elevates us with its transformative message and music.

The album’s title track scurries along a rollicking groove, mimicking the urgent fervor of choosing to follow good or evil in these last days. We can almost see Satan chasing his followers around, and God chasing Satan back to hell in this boisterous, rapturous soul rocker. Walk with Me sways soulfully as the singer utters a prayer and a fervent desire that Jesus will walk with her, while Call on Him rides along the musical phrasing of Wilson Pickett’s 634-5789, even opening with the words “If you need sweet Jesus / Call on Him” in the stead of “If you need good loving / Call on me.” King demonstrates the mighty power of her voice in her stunning a cappella delivery on Blessed Be the Name; the years have not diminished King’s ability to dwell in a phrase and deliver the vibrant and rich tone of every note she sings. The album closes with a spare and moving version of Mississippi Fred McDowell’s You’ve Got to Move, and King wrings every bit of emotion out of our souls on her version; she closes the album as she opened it, carrying us out of ourselves to a different world.

Every song on Living in the Last Days is King’s precious gift to us, and we’re grateful for the riches she shares with us in her vocals and in this album that does indeed move us deeply, musically and lyrically. It’s certainly one of the best albums of this year.

—Henry L. Carrigan Jr.

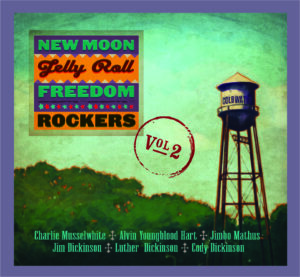

NEW MOON JELLY ROLL FREEDOM ROCKERS

New Moon Jelly Roll Freedom Rockers Vol. 2

New Moon Jelly Roll Freedom Rockers Vol. 2

Stony Plain – SPCD 1417

There’s really no mystery about what would happen back in 2007 when Jim Dickinson, Charlie Musselwhite, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Jimbo Mathus, and the North Mississippi Allstars convened in the recording studio at Zebra Ranch in Independence, Mississippi. They did what they’ve always done; they jammed on the blues—Hill Country, Delta, and Memphis style. New Moon Jelly Roll Freedom Rockers Vol. 2 picks up exactly where last year’s Vol. 1 left off. It’s almost like the band took a break after the opening set at the local juke, and now they’re back for the late show. In fact, both recordings boast the loose, raw feel and the give-and-take exchange between musicians that characterizes a live performance.

Because Jim Dickinson passed away in 2009, there’s an added poignancy to the two volumes, but here he is delivering a raucous version of Charles Mingus’ Oh Lord, Don’t Let Them Drop That Atom Bomb on Me; a great barrelhouse piano showcase on Jimmy Reed’s Can’t Stand to See You Go; a rocking version of Junior Wells’ Messin’ with the Kid that spotlights Musselwhite’s unparalleled harmonica mastery; and a pensive take on Memphis Slim’s Blues Is a Mighty Bad Feeling. As the title of Dickinson’s memoir asserts, “I’m Just Dead, I’m Not Gone.” Hart has two feature numbers this time around, a buoyant, rocking cover of Sir Doug Sahm’s She’s About a Mover and an acoustic slide guitar, harmonica, mandolin workout on his original Millionaire Blues (If Blues Was Money). Mathus takes over on two numbers, which range from the slippery shuffle Searchlight (Soon in the Morning), featuring a dramatic solo by Musselwhite, to the rowdy string band–inspired Greens and Ham. Musselwhite takes the helm for two songs, and he’s just stunning. With six decades of playing this music, rooted in Memphis and schooled in Chicago, the harmonica player/vocalist exhibits an absolute mastery of the form, and he shines in this setting surrounded by simpatico players on the haunting Black Water, featuring a devastating dialogue with one of the guitar men (it would have been nice if they had identified the soloists on each track), and the chugging Blues for Yesterday that highlights the propulsive groove mastery of bassist Chris Chew and drummer Cody Dickinson. This volume features a bonus, in that Luther Dickinson gets to step into the spotlight for an instrumental, Earl Hooker’s Blue Guitar that boasts a dynamic slide guitar/harmonica exchange. What you see is what you get on New Moon Jelly Roll Freedom Rockers Vol. 2, and what you get is an impromptu set of dynamic Mississippi blues in all its glory.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

DAVID ROTUNDO BAND

So Much Trouble

So Much Trouble

Dream We Share – No #

A protégé of Danish harmonica star Lee Oskar (of ’70s funk-rock-soul group War), Canadian musician David Rotundo sings, plays harmonica and occasional guitar, and writes all of the music on So Much Trouble, his fifth album.

Toronto-based Rotundo launched his first band in 1997, and was first heard on record when he released Blowin’ for Broke in 2001. After extended runs with the Blue Canadians and the Jack de Keyzer Band, Rotundo put together his eponymous group in 2003; that same year the new aggregation released Blues Ignited, featuring guitarist Enrico Crivellaro. A well-received 2007 set, Live at Roc’N Doc’s served as a document of the band live onstage. After 2009’s No Looking Back, fans of Rotundo’s music would have to wait more than a decade for a follow-up.

So Much Trouble is a showcase of the breadth and depth of Rotundo’s musical vision. Co-produced by Oskar, the 12-song set features swinging, up-tempo blues (She’s Dynamite); searing, soulful, slow jams (I Must Be Crazy); stripped-down country blues (Hard Times Coming); and more.

The record’s title track is highlighted by Ron Weinstein’s lovely Hammond organ and dialogue between Skylar Mehal’s arena-rock lead guitar and Rotundo’s blues harp. While vocals on most of the album’s first half feature only Rotundo, the second half folds more voices into the mix, to good effect. Of special note is Annie Jantzer’s singing and occasional wordless vocalizing on Too Blue.

Throughout the record, Rotundo’s harmonica work is spot-on, and the song arrangements work it skillfully into the mix, allowing space for the other musicians to shine (and occasionally spar) with it. Cellist Phillip Peterson sounds like a full string section on the deep groove Funky Side of Town, one of the strongest and best-arranged cuts on the set.

Drinking Overtime is either live-in-the-studio or designed to sound that way. Loose and limber, it’s a rollicking good-time number about beer, replete with solo turns on organ and harmonica—and then, after another verse—more harmonica. Saxophone makes a welcome appearance on the smoldering and understated That Thing Called Love, one of the album’s 11 originals (the album closer, Trouble in Mind, is public domain).

But the undisputed standout tracks on So Much Trouble are the two that find Rotundo, his band, and guest players pulling out all of the stops. Trying to Find It won’t ever be cited for deathless lyrical content, but musically, it exemplifies what the David Rotundo Band is all about, and documents the group in the best possible light. The tune and its arrangement may remind some listeners of Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes.

After an elegiac, piano-centric number (the gospel-flavored Foolish Love), Rotundo and band launch into Long Road, a song that builds from a simple start into a soaring, wide-screen production featuring tabla, Latin percussion, and no less than ten vocalists. The song itself is a cross between a field holler, gospel, country blues, and world music (with a string section). Listeners who stick around through the already quite enjoyable first ten tracks are richly rewarded with Long Road.

—Bill Kopp