SHEMEKIA COPELAND

SHEMEKIA COPELAND

Uncivil War

Alligator Records – AL 5001

Uncivil War finds Shemekia Copeland holding steady on the course she’s been traveling, melding her bona fide blues roots with various elements that carry her into the realm of what has come to be called Americana; in other words, she’s mixing her blues with elements of soul, gospel, rock, funk, and country, and it works. This latest effort, which follows her award-winning America’s Child (2018), features less of an emphasis on the social/political consciousness material; however, those types of themes still run through the selections, just not as overtly as last time.

Throughout her recording career, Copeland has been matched with really top-flight producers, including Mac “Dr. John” Rebennack and Steve Cropper. This time around she returns to the studio with Will Kimbrough, who produced her last album. One of things that makes Uncivil War so effective is the fact that even though a number of high-profile guests show up, Kimbrough assembles a solid, stripped-down, core band—himself on guitar, Lex Price on bass, and Pete Abbott on drums—that gives her the perfect support she needs, which isn’t much, considering she’s such a powerful vocalist, and it also gives the program a unified sound and feel. It plays like an album, not just a collection of disparate tracks.

While the selections feature some well-chosen covers, the bulk of the songs are co-written by Kimbrough and executive producer John Hahn. One of the things they seem to have discovered is that Copeland is very good at bringing alive songs that tell a story or examine characters, and they give her some compelling material with which to work. A funky blues, Clotilda’s on Fire, featuring Jason Isbell on lead guitar, details the disastrous narrative of the last ship to bring enslaved Africans into the United States. Its wreck was recently discovered at the bottom of Mobile Bay. The tremolo guitar intro that opens Walk Until I Ride immediately evokes Pops Staples, and the socially conscious message of this rootsy gospel number, embellished with Jerry Douglas’ lap steel, pays homage to the early Staple Singers. The title track definitely shows the influence of the Nashville locale for the recording, as Copeland walks the line between country and R&B, benefitting from contributions by Douglas on dobro, Sam Bush on mandolin, and Steve Conn on Hammond B3 organ. Over 20 years ago, Copeland was the youngblood setting the blues world on fire. Current blues wunderkind, guitarist Christone “Kingfish” Ingram ignites Money Makes You Ugly. Abbott’s second line groove on drums appropriately opens Dirty Saint, a salute to Rebennack, who passed away in 2019. The deeply simpatico relationship she had with the New Orleans pianist was apparent on their 2002 collaboration, and the affection she has for the man is clear here. She addresses gun violence on Apple Pie and a .45, with its steamroller blues groove, and challenges gender stereotypes on She Don’t Wear Pink that features a loping Chuck Berry–like beat. No Heart at All is a hard-driving rocker about spurned love. The program also includes some choice covers: a gender inversion on Under My Thumb, one of the most misogynistic of Rolling Stones songs (which is saying a lot); Shawn Mullins’ critique of religious intolerance, Give God the Blues; the funky R&B of Junior Parker’s In the Dark with Cropper on lead guitar; and a knockout version of her father, Johnny Clyde Copeland’s R&B ballad Love Song. Shemekia Copeland proves on Uncivil War that she is once again a winner.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

BOBBY RUSH

BOBBY RUSH

Rawer Than Raw

Thirty Tigers / Deep Rush Records – 51181CD

At age 86, bluesman Bobby Rush has nothing left to prove. Recipient of a dozen Blues Music Awards, dozens of Living Blues awards, and winner (for Porcupine Meat) of the 2017 Grammy Award for Best Traditional Blues Album, Rush could be forgiven if he chose to rest on his laurels, looking back proudly on an impressive body of work that extends over a 50-plus-year period.

It’s quite clear that’s not his plan. His latest album, Rawer Than Raw, is steeped in the history of blues, and re-emphasizes Bobby Rush’s place within that history.

Listeners who tuned in to Rush’s early singles—exemplified by 1971’s Chicken Heads—were entertained by his playful and irreverent approach to songcraft. But a career-spanning four-CD compilation released in 2015, Chicken Heads: A 50-Year History of Bobby Rush, placed the sillier moments into the larger picture of an important blues figure. Along with his contributions to blues documentaries (an episode of Martin Scorsese’s The Blues, Martin Shore’s Take Me to the River), albums like 2013’s Down in Louisiana and Sitting on Top of the Blues from 2019 serve to underscore the fact that Rush is both a serious student and practitioner of the blues.

That point is hammered home with the release of Rawer Than Raw, a one-man show of an album in which it’s just Bobby Rush, his voice, his acoustic guitar, and his trusty harmonica. Recorded—on location, one might say—in Jackson, Mississippi, Rawer Than Raw splits the difference between a modern, state-of-the-art recording and a kind of one-mic audio verité document. The vibe might be raw, but the performance is polished, informed by a lifetime immersed in the music.

The album opens on its theme with the original Down in Mississippi, featuring Rush’s spirited harmonica work that extends after the guitar and voice have finished. The primitive blues of Skip James’ Hard Time Killin’ Floor Blues (as Hard Times) shows another side of Rush’s blues persona. Rush’s lean, sinewy acoustic guitar leads convey more passion and energy than most electric players can put across with a wall of amplifiers.

Chestnuts like Howlin’ Wolf’s Smokestack Lightning have been waxed by countless blues musicians, but Rush makes the song sound as if he wrote it himself. His hypnotic repeated guitar figures are the musical equivalent of a locomotive gearing up for a long journey, and his harmonica evokes mental images of itinerant musicians traveling by boxcar. Rush talks to the listener between phrases, adding an even more intimate and personal feel to the recording.

The song sequence of Rawer Than Raw alternates between Rush originals and blues classics (Robert Johnson’s Dust My Broom, Sonny Boy Williamson II’s Don’t Start Me Talkin’, Willie Dixon’s saucy Shake for Me). But the flow of the songs is such that they all fit together seamlessly as a listening experience. For listeners who can’t witness him live onstage—and in 2020, that’s everybody—Rawer Than Raw is the next best thing to experiencing Bobby Rush in a solo performance.

—Bill Kopp

REV. JOHN WILKINS

REV. JOHN WILKINS

Trouble

Goner Records – No #

“Why should the devil have all the best tunes?” is a query variously attributed to Martin Luther, Methodist progenitor John Wesley, and Salvation Army founder William Booth. You could add Robert Wilkins to this list of apocryphal attributions, since Wilkins recycled some of his best pre-war blues songs into sacred ones after becoming a minister of the Church of God in Christ. Here, his son John tears a page from his dad’s playbook, even if he can’t claim to have created the song that inspired this album’s striking God Is Able, not to be confused with other songs by that title. Complete with vocal call and response, courtesy of Wilkins’ daughters Tangela Longstreet, Joyce Jones, and Tawana Cunningham, this is the Ray Charles version of The Night Time Is the Right Time rewritten and sent back to church, complete with a hot testifyin’ vocal solo à la Raelette Margie Hendrix on Charles’ 1958 classic. A vivid reminder of where soul came from, it’s one of several pleasant surprises on an album that covers acres of stylistic ground.

The title track and album opener, with its oblique references to school shootings and a dysfunctional White House, can’t help but recall some of Pops Staples’ civil rights–era topical songs, albeit delivered with a heavier and thicker rock groove than heard on ’60s-vintage Staple Singers sides. If Trouble poses problems, the funky following track, Down Home Church, suggests a solution: Wilkins is pastor of Hunter’s Chapel in Como, Mississippi, to which he invites listeners in this song. You Can’t Hurry God applies the structure and pacing of the Otis Redding–era soul ballad to a message for impatient believers, echoing the guitar lines a youthful Wilkins laid down on O.V. Wright’s 1965 single You’re Gonna Make Me Cry. Grandma’s Hands finds Dad and daughters revisiting the 1971 Bill Withers hit, while the daughters alone harmonize sweetly on Ralph Stanley’s The Darkest Hour, adding waltz time country gospel to the musical mix. The venerable spiritual Wade in the Water gets a funky full band treatment while Walk with Me finds Wilkins playing acoustic guitar solo and singing with one of his daughters in a performance that’s moving in its spare simplicity, reminiscent of his father’s sacred music. The album closer, Storm and Rain, is an urgent update of Get Right Church, a song Fred and Annie Mae McDowell sang at Hunter’s Chapel back in the mid-1960s.

Produced by Amos Harvey and featuring “first call” Memphians on guitar, keyboards, bass, and drums, Trouble is a distinctly down-home mix of disparate gospel strains that honors a family tradition while moving agreeably in the present tense.

—Mark Humphrey

JOHNNY RAWLS

JOHNNY RAWLS

Where Have All the Soul Men Gone?

Third Street Cigar – No #

This is soul man Johnny Rawls’ third outing for Ohio-based Third Street Cigar, following closely on the heels of 2019’s I Miss Otis Clay and 2018’s I’m Still Around. It was recorded at Heyman Studios in Copenhagen (with overdubs added at Bigfoot Studios in Waterville, Ohio) in the course of Rawls’ month-long European tour in early 2020 that also yielded Johnny Rawls Live in Europe on the Dutch CRS imprint. Like the live set, Rawls is backed here by the Ozdemirs, a German trio consisting of Erkan Ozdemir on bass and his sons Kenan and Levent on guitar and drums, respectively. Italian keyboardist Alberto Marsico was present on both dates, and the Ohio overdubs added veteran Toledo guitarist Larry Gold on two tracks, along with a horn section comprised of Travis Geiman on trombone and Mike Williams on alto sax on nine, the lone exception being Calling on Jesus, the gospel rave-up that closes the proceedings.

From the first notes of the title track, it is evident that Rawls’ European bandmates know what they’re doing, laying down an easy-rolling groove as Rawls name checks such predecessors as Little Willie John, Bobby Bland, B.B. King, Otis Redding, Percy Sledge, and, of course, his close friend Otis Clay and longtime employer, O.V. Wright. Unlike its live companion, which includes covers of Wright, Tyrone Davis, and Clarence Carter, among others, the ten tracks on offer here are all Rawls originals. Medium tempos prevail, propelled by Rawls’ mastery of rhythm guitar and cushioned by Marsico’s organ and the horn section, the latter’s blend of trombone and alto sax resulting in a higher and lighter sound than the more common pairing of trumpet and tenor. Lyrically, there’s nary a cheating woman to be found amidst such affirming songs as Bottom to the Top, Can’t Leave It Alone, and Love, Love, Love, with its bluesy guitar intro. Elsewhere, Rawls speaks the truth about Money and Time (“Someone tell me where the years have gone, how time slips away / All I have is some photographs of memories of yesterday”), bemoans “the strange situation that we’re living in today,” on Town Too Small, and reassures us that he’s going to keep on playing his guitar and singing his songs until he drops on Keep on Doing My Thing.

It is apparent from the titles of this and his other recent releases that Rawls has become keenly aware of his position as an elder statesman on today’s southern soul scene. As such, we should cherish the ongoing opportunity to relish the continuing presence of Rawls and other veteran soul men such as William Bell and Don Bryant. Rawls himself has never released a bad album among the 20 or so in his catalog, and this one is no exception.

—Jim DeKoster

JOHNNY IGUANA

JOHNNY IGUANA

Johnny Iguana’s Chicago Spectacular!

Delmark Records – DE-864

Pianist Johnny Iguana (born Brian Berkowitz) may not have been born in Chicago, but he’s long since made the Windy City his home, and his understanding of Chicago blues is deep and finely textured. Iguana comes from—and is central to—a scene that extends beyond the blues; he’s grounded in punk, jazz, R&B, and rock ’n’ roll as well. But there’s a definitive blues sensibility that fuels whatever musical endeavor to which he applies his inimitable talents. Among his credits: he played with Junior Wells for three years, was a key player in the 2015 all-star tribute project Muddy Waters 100, and he currently leads the wonderful (and wonderfully hard to classify) Chicago band the Claudettes.

But for his latest project, Iguana has focused his attention squarely upon the blues. The dozen cuts on the aptly named Johnny Iguana’s Chicago Spectacular! showcase his forceful yet precise command of the piano keyboard. He’s joined by an impressive roster of sidemen, including guitarist Bob Margolin (on an incendiary reading of Roosevelt Sykes’ 44 Blues), John Primer, Lil’ Ed Williams, Billy Boy Arnold, and many others.

Yet, it’s Iguana who remains at the center of this particular musical universe. His rollicking piano work is deeply expressive, and he coaxes an astounding swath of variety out of the acoustic instrument. Iguana’s approach to playing is a case-in-point reminder that the piano is as much a percussive instrument as anything else. And he rocks the daylights out of the thing, sometimes playing with dizzying speed (check his original Big Easy Women), other times taking a more slow and nuanced approach (as on his cover of Otis Spann’s Burning Fire). And then there’s his original Land of Precisely Three Dances, in which Iguana displays both approaches, back and forth, in the context of an instrumental lasting under three minutes.

In an era dominated by digital downloads, Johnny Iguana’s Chicago Spectacular! proudly heads in the opposite direction with its CD release: the album features extensive liner notes by acclaimed Chicago-based music historian Bill Dahl, including brief biographical sketches of some of the city’s most important ivory-ticklers. Dahl gently (yet convincingly) makes the case that Johnny Iguana is earning a place among those names. And in a time when most studio recordings make use of digital plug-ins and virtual instruments, Iguana’s instrument of choice on this record is a 100-year-old Chicago-built upright piano.

As is the case with his work in the Claudettes, Johnny Iguana’s Chicago Spectacular! defies easy classification. True enough, he’s covering songs by Spann, Sonny Boy Williamson I (his version of Stop Breakin’ Down which featured Big Maceo) and Willie Dixon (Down in the Bottom). And he bends songs chiefly thought of as guitar tunes (like Elmore James’ Shake Your Moneymaker) into piano-centric forms.

But he also ventures beyond the blues to tackle the soulful Lady Day and John Coltrane by Gil Scott-Heron. And Iguana’s original compositions fit seamlessly into the context of the great compositions written by blues giants. In fact, it’s a testament to Iguana’s taste, eclecticism, and superb musicianship that all of the pieces selected and/or written for the album hang together as a cohesive and splendidly satisfying whole.

—Bill Kopp

JOHN NÉMETH

JOHN NÉMETH

Stronger Than Strong

Nola Blue – NB 013

On 2017’s Feelin’ Freaky, Memphis-based vocalist/harmonicist John Németh wove hip-hop and rock accents into his music’s signature soul blues vibe. His latest CD, Stronger Than Strong, draws from a purer vein, with Németh and his band, the Blue Dreamers, mingling evocative balladry with tunes that kick up a righteous ruckus.

This is not to suggest that Németh, who wrote ten of the dozen tracks here, has nothing but escapism to offer. The sturdy 4/4 Chain Breaker (co-written by Jaki Taylor and Blue Dreamers bassist Matthew Wilson) features Németh alluding to current crusades for social justice: “People of great character can’t seem to advance / ’Cause the color of their skin, there ain’t a fightin’ chance.” The smooth groove of Bars likewise salts its elegiac hard-time lyrics with a cutting reference to “a leader with a hand up your dress,” and a bracing sincerity graces Németh’s velvety take on Jesse Belvin’s Guess Who, on which Wilson contributes a piercing, clear-hearted guitar solo.

This sort of forthright strength runs vibrantly throughout Stronger Than Strong. The chugging rhythms of 19-year-old Philadelphia guitarist John Hay propel the gritty Deprivin’ a Love, with its stirring call-and-response vocal bridge, and the axman gives a stinging surf rock vigor to the bop-a-licious Throw Me in the Water. Németh’s versatile voice is on vivid display, whether it’s his authoritative low croon on Work for Love, which also offers a nimble harp solo, or the gospel-tinged vitality of I Can See Your Love Light Shine, with Németh evoking the album’s title phrase to describe the sheer power of his passion.

It is indeed these moments of energetic optimism that find Stronger Than Strong at its most memorable. Album opener Come and Take It serves up the Blue Dreamers at their greasiest, with a touch of distortion to Németh’s vocals and a swaggering wail in his harp playing. Danny Banks’ dauntless drums drive the bombing-down-the-highway Fountain of a Man, a showcase for Németh’s most ferocious solo of the disc. Even a rough-luck love song like She’s My Punisher offers plenty of sweet with its bitter, and the whole affair wraps up with Sweep the Shack, Németh’s bell-clear vocals tussling with Hay’s playful guitar fills. No question here: when he called this one Stronger Than Strong, Németh wasn’t pulling our legs.

—Matt R. Lohr

KIRK FLETCHER

KIRK FLETCHER

My Blues Pathway

Cleopatra Blues – CLO 1900

Kirk Fletcher expands his horizons by looking back and retracing his steps on My Blues Pathway, a musical retrospective on myriad influences that have shaped his career, which is steadily evolving based on this impressive outing. The album opens up with an original tune, Ain’t No Cure for the Downhearted, which has a funky R&B vibe with a prowling organ underneath, reminiscent of Robert Cray. Fletcher doesn’t wasted time getting right to the point, with sharp lyrics and a snappy solo occurring after the first verse.

No Place to Go (co-written with former longtime Robert Cray bassist Richard Cousins) has revealing, semi-autobiographical lyrics that describe his career’s journey—traveling all around the world only to find that home is ultimately the only place to be. Love Is More Than a Word slows things down even more, with a Memphis-flavored soul song (also co-written with Cousins). Well-crafted verses, a catchy chorus, and percolating guitar solo create the perfect combination for this Stax-driven ballad.

Struggle for Grace definitely has a Thrill Is Gone vibe to it—it’s a medium-slow minor blues progression with a tight snare pop, a warm blanket of horn harmony underneath, and lyrics that reflect Fletcher’s daily challenge to stay strong and hold on under overwhelming odds. The R&B-flavored I’d Rather Fight Than Switch (originally recorded on U.S.A. label in 1965 and written by tenor saxophonist A.C. Reed) serves as a testimonial, with lyrics appropriately adjusted to reflect the guitarist’s personal perspective. One of the best solos on the album appears after the final verse—his stinging Cray-flavored approach is sensational.

Heart So Heavy is more demonstrable of Fletcher’s original touch, both on vocals and guitar. As a straightforward blues, this song fits him like a glove, and represents one of the strongest on the entire disc. The backing horn section really drives it home underneath the blistering guitar solo during the finale.

Fattening Frogs for Snakes offers a modern feel to Sonny Boy Williamson II’s 1957 Checker label classic, with updated lyrics to reflect Fletcher’s current mindset in 2020. It’s a clever nod to Fletcher’s Arkansas blues roots. Meanwhile, the soul-struttin’ groove of Place in This World Somewhere is borrowed from fellow blues guitarist Chris Cain’s 1992 Blind Pig recording. Don’t forget to check out the bop-flavored jazz licks Fletcher spits out at the end of this solo—it’s a pleasant surprise.

D Is for Denny, an instrumental track co-written by Richard Cousins, is a driving Texas-twang shuffle with horn section riffs led by tenor saxophonist Joe Sublett (overdubs recorded by Joe’s Phantom Blues bandmate Johnny Lee Schell at his Ultratone Studios). The main melody serves as an infectious hook that already has the sound and feel of a blues classic. Life Gave Me a Dirty Deal really takes us back to the South with the old-school Juke Boy Bonner tune, delivered with the sparse sound of the stripped-bare naked National steel guitar and juicy blues harp of none other than Charlie Musselwhite.

Although Kirk perceives this project as a blues offering, it feels more like equal parts R&B, soul, funk, and gospel—blended well to create the perfect blues roux. It’s clear that Fletcher has stepped up his game, writing strong original lyrics that reflect what’s inside his heart—and that just might be more important on this album than the superb guitar playing Fletcher delivers so consistently.

—Wayne Goins

DAVID KIMBROUGH JR.

DAVID KIMBROUGH JR.

Say You Don’t Love Me: The Last Recordings of David Kimbrough Jr.

Dolceola Recordings – DOLC-1009

Field recordings tend to be associated with an earlier era, that of Lead Belly and the Lomaxes especially, yet field recordists still document down-home sounds. Japan’s Dan Torigoe has visited the American South with “old school” equipment (a portable reel-to-reel Ampex 601 tape recorder and a ribbon microphone RCA 77DX) and has filmed and taped extensively for his Tokyo-based Dolceola Recordings label. This is the label’s fifth release, available on vinyl, CD, and as a download.

Torigoe visited David Kimbrough Jr. in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in October 2017 and recorded him on his front porch. Son of Junior Kimbrough, David was a multi-instrumentalist (he played keyboards in church and even mountain dulcimer) who extended the Hill Country blues sound of his father into what came to be called Cotton Patch Soul. Kimbrough succumbed to cancer on July 4, 2019, aged 54.

The session opens with Kimbrough casually introducing the album’s title song, one he learned from his father and that makes its debut here. Then his Fender Stratocaster, recorded “dry” with no effects, commences a relaxed lope that’s reminiscent of Tommy Johnson’s Maggie Campbell Blues. Kimbrough sings in a high, plaintive voice, pleading for a lover’s reunion that’s not to be. You can hear the rain in the background at the outset of Done Got Old, a confessional ramble in which Kimbrough’s vocals fall squarely between the church, where he had been earlier on the day of these recordings, and the blues. “Can’t do the things I used to do,” he opines, “I’m an old man.”

The informality of this session is nowhere more evident than on Half Past a Monkey’s Azz, which opens with Kimbrough rehearsing the lyrics and the groove to the song before starting. A truck rumbles by in the background. He’s far surer of I’m Leaving You Baby and its relaxed funk blues groove. The album’s standout is its closing track, the nine-minute Lonesome Road / Lord Have Mercy on Me, the epitome of the strong confessional strain in Kimbrough’s best songs along with the natural way he blended Saturday night / Sunday morning pleas (“God know I tried, child,” he sings, “I tried hard to treat you right . . .”).

This “last session” was also Kimbrough’s first without any accompaniment other than his own guitar. Its seven songs and 40 minutes are a spare snapshot of an afternoon of shared music that’s moving, if not overwhelming, made more poignant by the artist’s untimely passing.

—Mark Humphrey

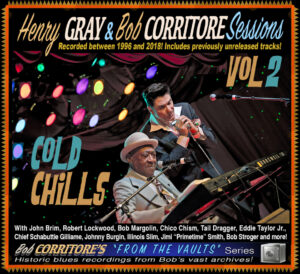

HENRY GRAY & BOB CORRITORE

HENRY GRAY & BOB CORRITORE

Henry Gray & Bob Corritore Sessions, Vol. 2

SWMAF – SWMAF-17

When pianist Henry Gray died in February of this year at the age of 95, one of the very last voices of the postwar blues era was silenced. Although for years he’d been living in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he’d grown up, his name will forever be associated in most blues lovers’ minds with Chicago, where he lived for over 20 years and worked with such luminaries as Jimmy Reed, Little Walter, Rice Miller (Sonny Boy Williamson II), and Howlin’ Wolf.

Phoenix, Arizona–based harpist and club owner Bob Corritore, who has dedicated most of his career to booking, working with, and recording immortals from that fabled blues era, cut multiple sessions with Gray between 1996 and 2016. This disc features tracks from 15 of those sessions, spanning the entire 20 years of their recorded musical relationship (Gray continued to travel to Phoenix to perform at Corritore’s club, the Rhythm Room, until 2018, after which his health no longer permitted him to make the trip).

The tracks, which include well-known standards, at least one Henry Gray original, and quite a few previously unheard or obscure rough-cut diamonds, aren’t in chronological order, and there are no recording dates given for most of them, but it’s clear that Gray’s gifts remained virtually undiminished, even in his 90s. From the first note of the searing Cold Chills (Gray’s personalized recasting of a Jimmy Reed standard, for which he takes composer credit) through Corritore’s final harp fade-out on Going Down Slow (on which Gray’s gutsy vocals and barrelhouse-rattling piano jubilantly belie the resigned pathos of the lyrics), his piano work is unerring, his voice brawny and sure (even if his Bayou State accent seems to have become more prominent over time). On harp, Corritore channels the spirits of the ancestors—both Walters, both Sonny Boys, Jimmy Reed—with unerring accuracy, but he infuses enough of his own imagination and musical personality to avoid slavish imitation.

Aside from the stellar performances from the co-leaders, though, the most remarkable thing about this set is the array of sidemen and accompanists on hand—start with Robert Lockwood Jr., John Brim, Chico Chism, Bob Stroger, Eddie Taylor Jr., Tail Dragger, and go on from there. All in all, this is a full-frontal blast of sounds that refuse to grow old, purveyed by some of their past and present masters—not nostalgia, not a “revival,” but an in-the-moment celebration of music and life.

—David Whiteis

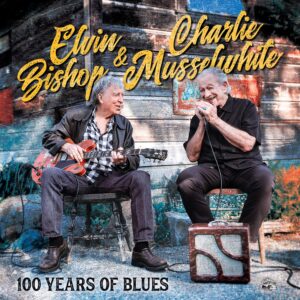

ELVIN BISHOP AND CHARLIE MUSSELWHITE

ELVIN BISHOP AND CHARLIE MUSSELWHITE

100 Years of Blues

Alligator – ALCD 5004

As graduates of Chicago’s 1960s University of Blues, harp ace Charlie Musselwhite and guitarist Elvin Bishop have seen it all and lived most of it during their decades of performing.

Bishop left his Oklahoma home for Chicago in the late 1950s after earning a scholarship to attend the University of Chicago, but he quickly ditched formal education to learn the blues at the feet of the likes of Howlin’ Wolf and guitarist Smokey Smothers before hooking up with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in the late ’60s. A solo career followed, built on his soulful, blues-rooted picking and his playful, countrified “Pigboy Crabshaw” persona, and peaked in 1976 with the smash Fooled Around and Fell in Love.

Musselwhite migrated to Chicago from Memphis in the early ’60s, where he honed his rich, hard-edged harp style by sharing stages with Muddy Waters, Junior Wells, the Wolf, and Sonny Boy Williams. He launched his solo career in the mid-’60s and has been enjoying a renaissance of late, thanks to a pair of exquisite releases with rock/roots artist Ben Harper, including 2013’s Get Up!, which won a Grammy Award for Best Blues Album.

On 100 Years of Blues, Musselwhite, 76, and Bishop, 77, mine the chemistry and down-home vibe created during a 2019 tour together to cook up a blues menu that’s as comfortable as a big ol’ plate of biscuits and gravy. With backing help from Bob Welsh on guitar and piano and Kid Andersen on upright bass—Andersen also produced the CD—the album features 12 warm and sparse songs, nine written by the duo.

The mid-tempo shuffle of Bishop’s Birds of a Feather kicks off the jam by introducing listeners to the pair and borrows liberally from Bishop’s stage banter. “It does my heart good to see people enjoying the show / so away we go” Bishop sings in his road-worn rasp.

West Helena Blues finds Musselwhite’s abundant harp skills on full display and his voice still in fine form. Bishop ventures into political commentary on What the Hell? “Look at the shape the country’s in / this situation is a shame and a sin,” he sings over a bed of fuzzed-up guitar and smokin’ harp.

Musselwhite reaches deep into his reservoir of world-weary experiences on songs like Good Times, If I Should Have Bad Luck, and Blues, Why Do You Worry Me?. “I wouldn’t listen to my people / my friends or nobody else / I had to make mistakes in life / I had to learn it all for myself,” Musselwhite declares.

The instrumental South Side Slide sounds like a Sunday afternoon front porch jam, while their take on the Willie Dixon classic Help Me is a highlight.

The autobiographical title track closes things, with the bluesmen sharing vocals and name checking some of their old Chicago mentors, as well as venerable ’60s Windy City blues haunts like Pepper’s Lounge and Silvio’s.

100 Years of Blues sizzles with a laid-back urgency that only blues survivors could create.

—Rod Evans