VARIOUS ARTISTS

VARIOUS ARTISTS

Ann Arbor Blues Festival 1969—Vols. 1 & 2

Third Man Records – TMR 239/240

Times they were a’ changing back in 1969—the first Vietnam draft lottery, a man walking on the moon, the Manson murders, and Woodstock would come to mind for most Americans, but if you were into the blues, the year is also remembered for the inaugural blues festivals at Ann Arbor, Michigan, on the first weekend of August and at Grant Park in Chicago four weeks later. It may be hard to believe at a time when it takes nearly 20 pages of LB to list all the festivals in 2019, but back in 1969, despite having blues sessions at the established jazz and folk festivals in Monterey and Newport, there had yet to be a blues festival per se in the United States. It was a great risk for the young promoters of the Ann Arbor festival to see if people would support an all-blues program at an open area on the University of Michigan campus.

The promoters aimed high, bringing in some of the music’s greatest names, young and not so young, and not only from the Midwest, but from Louisiana, Texas, California, Mississippi, and Memphis as well. The concept was certainly well received by the musicians, as Magic Sam likened it to “an All-Star Game” and Louis Myers viewed it as “a family reunion.” Fortunately, one of the promoters, Jim Fishel, had the foresight to record virtually the entire proceedings on a friend’s portable tape recorder—and to keep the tapes for the next half century, until arrangements were made for Third Man Records to release this collection of one track each from nearly all of the performers, the only exceptions arising from the loss of the tape from the Sleepy John Estes / Yank Rachell segment, and the failure to obtain consent from the estates of Freddie King and Otis Rush, although Rush’s representatives did agree to the inclusion of a performance from an indoor concert at the university the following spring. The music is available in multiple formats—volumes 1 & 2 as either separate or bundled two-LP sets, a deluxe four-LP box set with expanded notes and reproduction of various artifacts, or as the two-CD set that provides the basis for this review—which, in addition to the pair of 70-minute discs presenting 23 artists, includes four full-panel photos and 36 more that are closer to postage stamp size (larger in the vinyl format), plus a 28-page booklet with 16 more photos, notes from Jim Fishel, Sophie Abramowitz, David Beal, and Parker Fishel, a photo index, and personnel listings for all performances.

The program starts off with the inspired choice of a raunchy Dirty Mother for You by 63-year-old pianist Roosevelt Sykes, whose recording career dated back to 1929, followed by his contemporary Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, before switching over to the up-to-date electric blues of Chicagoans J.B. Hutto, Jimmy Dawkins, and Junior Wells (with Lefty Dizz on guitar in place of Buddy Guy, who would be on the bill at Monterey the following month). Next up is headliner B.B. King, with an extended out-of-tempo guitar rumination leading into the slow dirge I’ve Got a Mind to Give Up Living, which he had previously recorded for BluesWay as All Over Again, followed by Mississippi Fred McDowell honoring King’s request that he play his version of John Henry. Luther Allison, still two weeks shy of his 30th birthday and awaiting the release of the LP he had recorded for Delmark earlier in the summer (making him the only feature act without his own album out; notably, his son Bernard played at this year’s festival), energized the audience with 15 minutes of vocal and guitar pyrotechnics on a slow blues medley before zydeco master Clifton Chenier provided a less frenetic moment singing You Promised Me Love in French. Howlin’ Wolf, with Lucky Lopez joining Hubert Sumlin on guitar, stretches out to nearly 17 minutes on Hard Luck Blues, the 1950 Roy Brown classic that Wolf had waxed for Chess just two weeks before, and the disc concludes with Otis Rush’s So Many Roads, So Many Trains.

Muddy Waters kicks off the second disc with the painful discovery that another mule’s been kicking in his stall, followed by an up-tempo harmonica showcase for Charlie Musselwhite (at 25 the youngest featured artist and, along with Sam Lay, one of only two still living) that provides Louis Myers a chance to challenge the festival’s more famous guitar heroes with his jaw-dropping solo. Next up, Magic Sam, who would be dead of a heart attack at age 32 by year’s end, offers up a warp-speed I Feel So Good (previously issued on Delmark) despite having to use a pickup rhythm section, after which Indianapolis-based guitarist Shirley Griffith offers his take on Jelly, Jelly Blues. The focus then turns to the West Coast with a ten-minute Call It Stormy Monday, a song that may elicit groans today but sounds fresh in the hands of T-Bone Walker, who first recorded it for Black & White in 1947 and also backs Big Mama Thornton on her iconic Ball and Chain. It’s then back to Mississippi with Big Joe Williams’ Juanita, while drummer Sam Lay takes the vocals on Key to the Highway before rejoining James Cotton’s band on a 14-minute Off the Wall that probably was more exciting in person. The concert closes with its oldest performer, 67-year-old Son House, and his emotionally raw Death Letter Blues.

As it happened, there would be only one more Ann Arbor festival in an all-blues format despite the presence of such high-profile artists as Bobby Bland, Albert King, Lowell Fulson, Junior Parker, and Buddy Guy in 1970. After a hiatus in 1971, the organizers rechristened the event the Ann Arbor Blues & Jazz Festival, allowing them to appeal to a wider audience by drawing on the star power of such artists as Miles Davis and Charles Mingus, while the blues programming placed greater emphasis on nearby Detroit bluesmen such as Eddie Burns, Bobo Jenkins, and Baby Boy Warren. Still, the 1969 festival was a landmark event that paved the way for the dozens of festivals that blues lovers can enjoy today, and in all likelihood played a role in convincing the founders of this magazine to take the plunge and go to press the next year. And a final note—if you’re worried about sound quality, don’t be. Yes, the sound varies from somewhat murky to razor-sharp depending on the recorder’s location, and yes, there are extraneous sounds of conversation, laughter, and cheering from the crowd, but the result captures the feeling that you were there better than a pristine recording from the board ever could.

—Jim DeKoster

TORONZO CANNON

TORONZO CANNON

The Preacher, the Politician or the Pimp

Alligator Records – ALCD 4995

Toronzo Cannon has certainly toughened up both his music and his message over the years—the good-timey celebrant of his early recordings is hardly recognizable in the tough-voiced, lyrically eloquent, and musically focused artist showcased here.

Cannon’s stylistic range spans from hard-grinding blues rock through urbane pop-soul balladry, Crescent City second-line revelry, and neo-Hooker blues boogie. He has matured into an expressive vocalist, incorporating elements of Johnnie Taylor–era deep soul into his blues-toughened delivery, and he’s toned down some of his Hendrixian excesses to hone a melodically rich guitar style that seethes with emotion but mercifully avoids pyrotechnic overkill. Probably most impressive, though, is his songwriting: his lyrics limn stories drawn from the front lines of everyday life, full of aphoristic wisdom laced with both humor and life-toughened resolve.

For this set, Cannon has gathered together an impressive array of guests along with his usual band, including guitarist Joanna Connor, harpist Billy Branch, and vocalists Nora Jean Bruso, Lynne Jordan, Cedric Chaney, and Maria Luz Carballo; Alligator Records CEO Bruce Iglauer even makes a spoken-word cameo appearance as “The Doctor” on Insurance, a caustic commentary on the vicissitudes of the US health care system. The N’Awlins-tinged Stop Me When I’m Lying, with some rollicking Fess-like piano from Roosevelt “Hatter” Purifoy and a jubilant horn arrangement by trumpeter Joe Clark, erupts with irreverent, carefree jubilance. By contrast, The First 24, set to an acoustic slide guitar accompaniment, is a brooding, death-haunted meditation on life, black history, faith, and fate, while the anthemic closer, I’m Not Scared, brings in the voices of a domestic abuse survivor (sung by Jordan), a bullied gay adolescent (sung by Chaney), and an immigrant struggling to survive (sung by Carballo) to bring an additional timeliness to Cannon’s message.

This is a first-rate outing by a still-evolving bluesman who’s just beginning to reach his full potential.

—David Whiteis

STONE GAS BAND

STONE GAS BAND

Up All Night

No label – No #

The original Stone Gas Band was a Delta blues institution for decades, accompanying harpist Arthneice “Gas Man” Jones in clubs and jukes around Clarksdale, Mississippi, and beyond until Jones passed away in 2013. This reconstituted version includes original members Terry “Big T” Williams (guitar), Harvell Thomas (bass), and Harvell’s brother Dione (drums and vocals), along with guitarist Andrew “Shine” Turner, harpist Billy Gibson, and keyboardist Howard Stovall. Up All Night, while obviously a tribute to Jones (he wrote or co-wrote six of the disc’s seven songs), should also be seen as a loving memorial to another late Delta master, Mr. Johnnie Billington, who also died in 2013 and had been a beloved mentor to several generations of Clarksdale-area blues aspirants.

Given that backstory, it’s no surprise that most of the music here should be shuffle-driven, good-time blues featuring sweet-warbling harmonica from Gibson (with strong echoes of Big Walter Horton in both his tone and melodic conceptions) and unadorned, precisely articulated guitar leads laid over deep-pocket comping from the Thomas brothers. But this is no by-the-numbers “roots” fest—Stovall’s organ work, though understated, adds a modernist sheen, and Dione Thomas’ vocals are graced with an R&B-ballad smoothness. In fact, even when the lyric imagery is pure cotton-patch blues (as in the ironically swing-flavored Up All Night), this band’s sound evokes uptown blues venues at least as much as it does the stereotypical (and, these days, mostly defunct) backroads wood-and-tar-paper juke. Offerings like the pop-tinged Been So Long, with its sweet-toned guitar leads and breezy rhythmic flow, make it even more evident that despite their undisputed Delta pedigree, the Stone Gas Band refuses to let itself be reined in or stereotyped by anyone’s preconceived notions of blues “authenticity.”

All of which means, of course, that the members of the Stone Gas Band are true carriers of the torch, updating and adapting their sound, as blues musicians always have, to incorporate the best of the old and the new. As such, they’re a fitting living tribute to the spirits of the beloved elders in whose name, and memory, they continue to keep the music alive and growing.

—David Whiteis

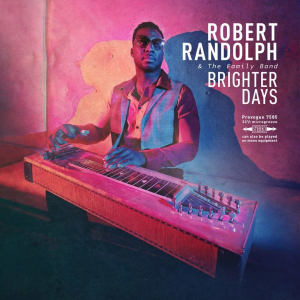

ROBERT RANDOLPH & THE FAMILY BAND

ROBERT RANDOLPH & THE FAMILY BAND

Brighter Days

Provogue – PRO 7585-2

Brighter Days have arrived for Robert Randolph. His family band includes Robert on pedal steel and vocals, sister Lenesha on vocals, his brother Marcus on drums, Danyel Morgan on bass, and Philip Towns on keys. Recorded in RCA studios in Nashville and also at Southern Ground (owned by Zac Brown), Dave Cobb successfully plays a dual role as both guitarist and producer on this album.

From the outset, the pedal steel guitar whines and moans on Baptise Me, a minor blues-funk where Randolph implores with a passionate plea, “I’m down on my knees, baptise me!”

A reverent, sanctified groove accompanies Don’t Fight It as Robert informs his listeners that resistance is futile and asks them to give up and give in to the “holy ghost power.” A screaming shout chorus ensues and builds pressure until a full-tilt boogie bursts forth, slowly increasing in tempo only to segue smoothly into the original funk.

Things simmer down immediately with Simple Man, a song written by Pops Staples and released in 1994 on Father Father from Virgin Records. Randolph sings it beautifully, even if the tune only lasts three minutes. Things slow down even more when Robert’s sister Lenesha shares vocal duties on Have Mercy, a song in a swinging 6/8 feel, with words dedicated to feeling alright about asking for help from up above (there’s some pretty nifty bass work from Danyel Morgan near the end, and it’s definitely worth the wait.)

Cut ’Em Loose is a seriously funky one-chord vamp that allows Randolph to soar higher than an eagle, with evocative lyrics that propel the music. Conversely, Second Hand Man grooves smoothly with well-crafted lyrics describing a “dumbass man” trying to sneak in the backdoor as a sidepiece to any woman that will take the risk. The repetitive out-chorus chant is quite catchy, indeed.

Lenesha makes a return appearance on Cry Over Me, this time keeping the reins all to herself. The southern, swampy vibe created by Randolph and band works as a perfect foil for her haunting, lyrical delivery on this pensive percolator. The highlight, however, is Robert’s screaming slide solo that serves as the soaring sendoff.

I Need You is Randolph’s personal confession and testimony, one that sums up the overall tone and purpose of the entire disc. Then, in the penultimate offering, Randolph delivers a wonderful rendition of Little Milton’s original 1971 B-side single from the Stax label’s recording of I’m Living Off the Love You Give. Unlike Milton’s motivating factor (presumably a woman), Randolph’s version can be better interpreted as his testifying to the need for the Lord’s precious love.

We get taken to church on the last rambunctious holy-rollin’ Strange Train, which invites everybody to hop on board and roll with the party that accepts all comers. It’s a fun way to end the gospel caravan.

Randolph’s slide sounds as good as it ever has, not to mention the lyrics, which are clean and tight, with a message that never misses its mark. He’s a uniquely gifted artist who’s always worth the time it takes to drop his platter on a turntable and give it a spin—in hopes to catch the spirit within.

—Wayne Goins

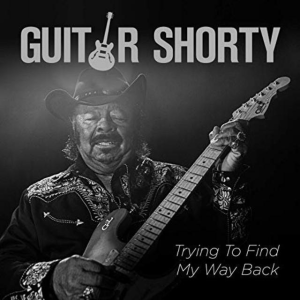

GUITAR SHORTY

GUITAR SHORTY

Trying to Find My Way Back

SDEG – 942 326 996-2

By his own account, Guitar Shorty was born David William Kearney in Houston, Texas, in 1939, although Eagle & LaBlanc submits that public records point to Loughman, Florida, in 1934. Either way, he’s now at an age where anybody not named Buddy Guy would be content to put his guitar down and savor a well-deserved retirement rather than maintain a touring schedule that would exhaust many a younger man, and record a new double CD in a style that bears little resemblance to his previous efforts.

Growing up in Houston and then Kissimmee, Florida, Shorty was something of a prodigy who played with Walter Johnson, Ray Charles, and Guitar Slim while still in his teens. He released his first record in 1957 after Willie Dixon caught his act while touring Florida with Otis Rush. Dixon arranged to bring him up to Chicago to record a 45 r.p.m. for Eli Toscano’s short-lived, but influential, Cobra label. While there, Shorty gave Buddy Guy, who Dixon was recording for Toscano’s Artistic imprint, some lessons in blues stagecraft. Shorty was next heard from two years later when he cut three singles with Bob Tate’s band for the obscure Pull label in Los Angeles, including his classic Hard Life, a minor-key lament straight out of the Cobra lexicon. Despite the quality of his recordings, and though he proceeded to back Sam Cooke in Los Angeles and marry Jimi Hendrix’s half-sister in Seattle, he did not make another record until an LP came out on Santa Monica–based Olive Branch in 1989. Fortunately, his public profile benefitted with a CD on JSP backed by Otis Grand’s band while on tour in Europe, followed by a trio of finely crafted discs on Black Top, another for Evidence, and three more increasingly rocked-out efforts for Alligator—hardly surprising for a man whom Hendrix listed among his mentors and inspirations.

During the nine-year hiatus between his last Alligator in 2010 and this new release, Shorty collaborated with the iconic iconoclast (and label owner) Jerry “Swamp Dogg” Williams on the latter’s two most recent releases, which also brought him into contact with co-producer Larry “MoogStar” Clemon, whose resume includes working with such funk groups as the Zapp Band and Cameo. As one might guess from Clemon’s stage name, he’s into electronics, and the credits list him on “Drums, Bass, Rhodes, Strings, Organ, Piano, Synthesizer, Horns, Synth Pad, Vocalizer [and] Background Vocals,” leaving Shorty’s guitar as the only other instrument on every track but one.

The 16-track program is equally spread over the two discs, and, save for Stephen Stills’ For What It’s Worth (Stop, Hey What’s That Sound), all of the songs are credited to the participants. Lyrically, they run the gamut from politics (No More War), to love (You Are My Light at the End of the Tull), lust (Wonna Get Layed), and spoken autobiography (Go With the Flow). Shorty himself is in good form both vocally and instrumentally, though the backing does overwhelm his voice at times. For the most part, the music is densely textured (more about texture than melody), with thudding riddims (more about beat than tempo), and judicious use of vocal distortion.

In comparison to his contemporary Guy, Shorty has shown a much greater inclination to travel new roads rather than being content to polish and refine his proven stylings. While some may applaud this choice, others might wish he had taken the more conservative path. However, they would do well to listen more than once before making a final judgment.

—Jim DeKoster

JOHN DEE HOLEMAN

JOHN DEE HOLEMAN

Last Pair of Shoes

Music Maker Series – MMCD203

At age 90, singer and guitarist John Dee Holeman is one of the last authentic old-school Piedmont bluesmen. His initial inspiration came from fellow Durham-area legend Blind Boy Fuller. That might lead one to expect an album of bouncy, laid-back, ragtime-flavored, fingerpicking, acoustic blues. That is definitely not the case with Last Pair of Shoes. Holeman wields an electric guitar and leads a band featuring Tad Walters on guitar and harmonica, Chuck Robinson on organ, Chuck Cotton on drums, with James “Bubba” Norwood on drums on tracks one, seven, and nine, through a program of raucous, bone-crushing, electric blues. He may have emerged from the Bull City blues tradition, but it sounds like he’s taken a lot of inspiration from Chicago stalwarts like Hound Dog Taylor, Muddy Waters, and Elmore James.

Things kick off with the no-holds-barred Chapel Hill Boogie. Compare this version to the acoustic duet that he did with Kenny Wayne Shepherd on the same tune from 10 Days Out: Blues From the Backroads (2007); the swaggering boogie agenda here definitely becomes apparent. Crunching electric guitars and stabbing harmonica runs mark Waters’ She Moves Me. Other tunes usually associated with Chicago blues that get the full-throttle treatment include Dust My Broom and Give Me Back My Wig. He does slow things down on Two Trains, with its stabbing organ and guitar punctuations. On Mojo Hand his commitment to boogaloo is just unrelenting. Cotton’s booming bass drum and Robinson’s droning organ shape an ominous backdrop for Holeman’s jagged-edged vocal on Shotgun Blues. Even the folkie staple John Henry gets the blistering boogie approach and calls to mind Fred McDowell’s late career work with a rhythm section. Last Pair of Shoes is an unabashed testimony to the resilience of the blues, and it wouldn’t be surprising if John Dee Holeman keeps on walking that walk for as far as those shoes will carry him.

— Robert H. Cataliotti

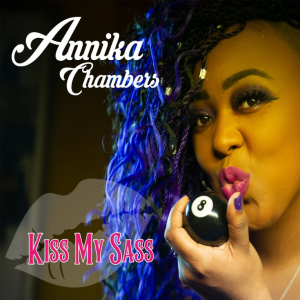

ANNIKA CHAMBERS

ANNIKA CHAMBERS

Kiss My Sass

VizzTone – VT-AC01

Just a few months after being honored at the 2019 Blues Music Awards as the Best Soul Blues Female Artist (and being featured in LB #262), Annika Chambers has released her third and finest album to date, proving herself worthy of that accolade. Only 34 years old and in the prime of a burgeoning career, the Houston native and her production team convened a stellar cast of special guests and supporting players to create this engaging ten-track set. Though several different backing contributors shine from time to time, the sonic spotlight remains firmly fixed, so to speak, on this dynamic singer and her capacity for impassioned interpretation. Chambers infuses each of the songs with her own verve.

One of the best is What’s Your Thing, an introspective number composed by the late Mack Rice. Featuring a guest turn by Ruthie Foster on background vocals and acoustic guitar, it unfolds like a gospel testimonial. Appropriately, it also challenges the audience to do some soul-searching. “Don’t let the color of my skin come between me and you, friend,” Chambers croons. In the chorus she declares, “My thing is love. My thing is freedom. My thing is peace,” which culminates in the rhetorical question, “What’s your thing?” Embellished with eerily fine touches on pedal steel by the musician known as the Mighty Orq, the production articulates this timeless message with power and grace.

Similarly, Brand New Day, co-written by Chambers and Larry Fulcher, is highly atmospheric. It’s a slow and moody blues with three-part instrumentation: luscious piano chords and fills by Randy Wall, an achingly poignant slide solo by the aforementioned Orq, and a gently driving bass groove by Fulcher. As it nears conclusion, Chambers unleashes her voice to wring multiple syllables, tones, and feelings out of the word “day” before jumping up an octave to end on a literal high note with the word “blues.” Her virtuosity seems absolutely natural, effortless, and beautiful—the antithesis of self-indulgent showboating.

Stay, written by Carolyn Wonderland and Eric Dane, is likewise a slow-paced number with effective instrumentation that weaves a fine backdrop for Chambers. Again, without ostentatiousness, her voice easily soars to end a line or prolongs notes with gritty vibrato. Meanwhile, Stephanie York-Blue contributes gospel-style flourishes on Hammond organ, James Wilhite lays down spicy guitar licks, and Anthony Terry conjures deep feeling via saxophone to accent the song’s emotional core. It all builds to a frenzied climax, with Nicoya Polar adding background vocals (as elsewhere on the record), before concluding with the falling action of Chamber’s lone voice.

Two Bit Texas Town—composed by another Lone Star State gal, Angela Strehli—rides a swaggering groove to proclaim the transformational power of the blues. Alluding to the great Chester Burnett’s iconic alter ego, the narrative recalls the profound impact of first hearing “the Wolf howl.” It also acknowledges by name various other blues artists that the neophyte fan soon discovers, “back when radio could turn your life around.” Between verses, Barry Seelen doles out an especially delicious solo on Hammond organ. Chambers follows up with a shout-out to the historic Houston radio station KCOH—which formerly introduced many folks to the long list of influential blues singers she cites as the song winds down.

Another standout track, the album’s closer is a fresh version of Chris Smither’s I Feel the Same, featuring Paul DesLauriers on slide guitar and shared vocals with Chambers. The minimalist strategy works as the stark instrumentation fills the spaces in this call-and-response duet. The two voices, distinctly different from each other, intertwine in a potently ardent dialogue befitting the confessional lyrics of a breakup song. It’s a stripped-down-to-the-essence blues in which sounds utterly complement the thematic content.

Great song selection, intelligent production, and lots of musical talent cohere effectively to make Kiss My Sass, and Chambers, strong contenders for more awards. The merits of this album, along with Chambers’ relative youth, also suggest that she may be maturing into one of the major blues women of the present day.

—Roger Wood

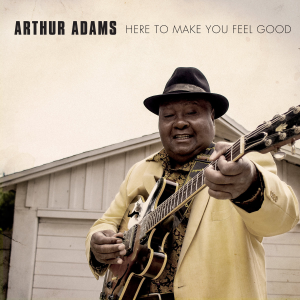

ARTHUR ADAMS

ARTHUR ADAMS

Here to Make You Feel Good

Cleopatra Blues – CLO 1407

The enormously amiable and amiably enormous Arthur Adams scores with an album that offers something good for everyone: soulful vocals, catchy songs, hot blues guitar licks. (As they said on American Bandstand, “It’s got a good beat and you can dance to it.”) The opener, Tear the House Down, offers an early ’70s soul funk groove that makes it easy to imagine a vintage Soul Train Gang dance clip as its video. Adams has scored in the past with dance material, so he leads with his strong suit here. Four songs addressed to the ladies follow, starting with Full of Fire (he is) and ending with Forgive Me (he hopes). In between are Sweet Spot, an endearing soul ballad (but bouncy) nicely framed by Adams’ guitar, and Pretty Lady, Adams’ Girl from Ipanema, a song for a cool but unreachable beauty: “Now when I go into town, I see you walkin’ on your way / I say, ‘Oh, how beautiful you are, I wish you would look my way.’” The song has a knockout keyboard hook and a wistfully sexy groove throughout, finally dancing into the mist on an extended Adams guitar solo.

The mood shifts dramatically with Gonna Make Some Money, in which Adams takes the role of an unemployed but hopeful guy seeking a new job. There are punchy horns and background vocals here, the added production muscle suggesting Adams and co-producer Hense Powell are betting this song’s a winner. (It’s the economy, stupid.) Then Adams returns to his upbeat lover groove in Enjoy Each Moment, a sunny valentine that would’ve sounded great on the radio in the summer of ’73. But it ain’t all good vibes: Adams goes full tilt blues on us with By Myself, the album’s sole lyrical downer: “Oh, when I wake up in the mornin’, I wonder why I feel so bad . . .” This is pure son-o’-B.B. stuff, driven home with crisp horns, wailing Adams guitar, and testifyin’ vocals.

The album almost closes with its title track, Here to Make You Feel Good. It’s a great groove song that, like others here, could’ve been a hit in another era. The album ends with Little Dab’ll Do Ya, an instrumental showcasing Adams’ down ’n’ dirty guitar framed by a tight bass-and-drums rhythm section and keyboards. A little dab o’ this does.

This is an irresistible album for anyone who loves the sound of late ’60s / early ’70s soul and funk, delivered with more upfront guitar than was the norm then. Adams co-wrote all the songs, and has a deep knack for pop song craft: “I try to think of what people would like to hear as they go through the day-to-day of their lives,” he’s said, and it shows. While the album can’t help recalling a classic era, there’s nothing self-consciously “retro” about it: it’s simply a veteran performer writing, singing, and playing in his idiom, delivering an album that makes good on its title song’s promise.

—Mark Humphrey

AL BASILE

AL BASILE

B’s Hot House

Sweetspot – SST9922

Al Basile continues his long, fruitful musical partnership with Duke Robillard on his new release, B’s Hot House. The Rhode Island–based singer, songwriter, cornetist, and poet’s latest collection of originals is as smooth and stylish as ever, ably abetted by guitarist and producer Robillard and members of his band.

Drummer Mark Teixeira, keyboardist Bruce Bears, and bassist Brad Hallen join Basile and Robillard once again, and the atmosphere they create evokes late nights at a cozy, smoky corner bar. In their prime element of urbane mid-century blues and R&B, the musicians keep to a mid-tempo or slower pace throughout, with the exception of the pumping, horn-driven Don’t Fool with the Truth. Basile’s burnished horn lines on tracks like So-Called Storyteller, Razor Wire, and I See You There glow like embers, while crunchy, punchy licks from Robillard provide sparks. Bears’ rollicking keyboard rhythms combined with Doug James’ and Jeff “Doc” Chanonhouse’s energetic horns give Looking for a Cookie a fun New Orleans flavor. Basile matches his earnest, conversational vocals with equally warm cornet solos on the yearning Can’t Keep Me from Dreaming and the wistful You Don’t Know Lonesome.

Consummate musicians all, Al Basile and company never fail to deliver the goods. For a mellow, sophisticated listening experience, stop in to B’s Hot House.

—Melanie Young

RONNIE EARL AND THE BROADCASTERS

RONNIE EARL AND THE BROADCASTERS

Beyond the Blue Door

Stony Plain – SPCD1407

Veteran guitarist/bandleader Ronnie Earl calls this “a band album—a community of souls with some guests, new directions and some good old down home blues . . .” Brand New Me is the sunny opener, an upbeat soul love song that was the title track of a 1970 Dusty Springfield album. Diane Blue, vocalist with Earl’s Broadcasters, sings it much as Aretha Franklin had on her 1971 cover, and Broadcaster pianist Dave Limina underlines the source by borrowing Aretha’s piano intro. The next song features one of the album’s guests, singer and harp virtuoso Kim Wilson, on Howlin’ Wolf’s Baby How Long, a convincing blues performance that has Earl going the distance on guitar. Wilson returns nine tracks later to blow harp on Wolf Song, an instrumental jam on Smokestack Lightnin’ which lets Earl showcase his Hubert Sumlin chops. Similarly, the instrumental T-Bone Stomp is a tribute to the shuffle king who laid out the basic vocabulary for electric blues guitar, T-Bone Walker.

The gospel-drenched depths of Ray Charles’ Drown in My Own Tears are plumbed in an instrumental performance showcasing guest tenor saxophonist Greg Piccolo alongside Earl’s guitar and Broadcaster Dave Limina on both Hammond B3 and piano. The after-hours mood it creates is extended further in Alexis’ Song, an Earl original that’s an instrumental dialogue between Earl’s guitar and Piccolo’s sax. Clocking in at a mere 1:38, it’s a sleek contrast to some of the “jam” tracks here, one of which is nearly ten minutes long!

Guitarist/vocalist David Bromberg is a guest who provides what may be the album’s most unusual (by contrast to the rest of the material) performance, a duo with Earl (and no one else) on Dylan’s It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry. Bromberg’s quavery voice is an instrument that’s arguably seen better days, yet the simplicity of the acoustic-electric guitar pairing, along with the blues lyricism of Dylan in his prime, makes this a mesmerizing performance. (Bromberg also wrote the album’s liner notes.)

The Earl original songs may not be on a par with the covers, though the playing is always on the money: Earl’s The Sweetest Man is a shuffle that affords its writer room for some tasty string bending and bandmate Limina some fancy flourishes on piano. But the covers rule, in part for eschewing obvious choices for half-forgotten gems. A case in point: Timmy Thomas’ Why Can’t We Live Together, delivered here with a vaguely Santana-like vibe and some subtly searing guitar from Earl. More assertive yet is the cover of Joe Simon’s Drowning in a Sea of Love (like the Thomas song from 1972), delivered with punchy horns, Earl’s twangy guitar, Limina’s Hammond B3, and Ms. Blue’s vocals. Honorable mention goes to Broadcaster bassist Paul Kochanski for his contemporary topical blues Bringing Light (to a Dark Time).

Earl, who has producer credit here, obviously had no restrictions in making an album with 15 tracks that delivers 72:44 of music! It covers a lot of stylistic ground, and while it may meander at times, the musicianship never wavers and longtime Earl fans are sure to feel it delivers the goods con brio.

—Mark Humphrey