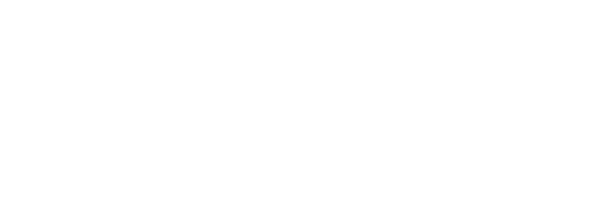

JONTAVIOUS WILLIS

Spectacular Class

Kind of Blue Music – No #

Kind of Blue Music – No #

With Spectacular Class, guitarist and singer Jontavious Willis extends the blues lineage that runs from Taj Mahal to Keb’ Mo’, the former serving as executive producer and the latter serving as producer and guest performer on guitar and mandolin. Willis’ largely solo, acoustic, debut album, Blue Metamorphosis, won the Blues Foundation’s International Blues Challenge 2018 award for Best Self-Produced CD. The sophomore effort from this 22 year old branches out with a greater emphasis on ensemble performances that survey a wide range of blues styles, highlighting his versatile and nuanced command of the form that makes it clear why these elder statesmen are drawn to mentor this fledgling blues talent. He was featured as an opening act for a number of dates on the recent TajMo tour.

Willis’ journey into the blues is reflective of both a rootedness in the tradition and the digital age. His first musical experiences came through singing gospel with his grandfather at the Mount Pilgrim Baptist Church in his hometown of Greenville, Georgia, and his inspiration to play the blues came from viewing a YouTube video of Muddy Waters performing Hoochie Coochie Man. The Taj Mahal influence is right up front on two tracks: the Delta-style acoustic duo performance of Daddy’s Dough that features a dialogue between Willis’ steel resonator guitar and Andrew Alli’s harmonica and The World Is in a Tangle, a funky string band outing with Keb’ Mo’ on mandolin, Phil Madeira on banjo, Willis on acoustic guitar, and the rocking rhythm section of Thaddeus Witherspoon on drums and Eric Ramey on bass.

The range of blues styles that Willis covers with a self-assured bravura that is evident in his deep, soulful drawl and nuanced guitar work is quite impressive. The Hill Country–inspired Low Down Ways proves once again that Hambone Willie Newbern’s Roll and Tumble Blues groove is infinitely adaptable and always compelling. The dual guitars of Willis and Keb’ Mo’ and Madeira’s surging B3 organ provide a dramatic backdrop for the singer’s soulful resonant delivery on the blues ballad Resting on My Mind that channels the classic Ain’t Nobody’s Business. Clarinetist Doug Mosher and trombonist Roland Barber join Willis on Long Winded Woman, a ragtime-flavored jaunt to New Orleans. The two guitarists, along with Madeira doubling on piano and B3, and the aforementioned rhythm section rock out on the 1950s R&B–styled instrumental Jon’s Boogie. On The Blues Is Dead, with its dynamic slide guitar, piano, and harmonica interplay, Jontavious Willis declares: “The blues ain’t going nowhere / Gonna be here for a great long time,” and Spectacular Class delivers some powerful testimony that he knows what he’s talking about.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

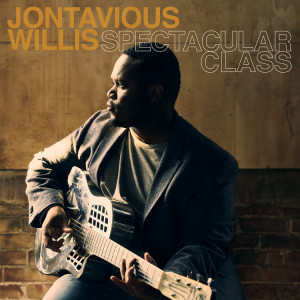

GRADY CHAMPION

Steppin’ In: A Tribute to Z.Z. Hill

Malaco – MCD-7553

Malaco – MCD-7553

Grady Champion loves the blues and does all he can to preserve the music, innovating within it while honoring tradition. On Steppin’ In he honors Z.Z. Hill, who died on April 27, 1984. Champion conducts a tour de force of the blues, bumping and grinding, shouting and moaning his way through a set of rumbling and raucous and down-to-the-bone tunes. He’s backed on the album by guitarist Will Wesley, bassist Frederick Demby Sr., keyboardist Sam Brady, and drummer Edward Rayshad Smith.

Wesley’s stinging guitar notes slither around Champion’s raw vocals and trembling harp on Open House at My House. The song starts off as a slow burner but soon opens into a full-throated blues shout. Champion’s wailing, insistent harp opens Bump and Grind; he lets it plead and urge on the bridge, with the pulsating rhythm pushing in a steadier and steadier move to climax. Eddie Cotton’s crisply biting lead guitar elevates the harp’s plaintive tones, carrying the rhythmic funk of the song higher and higher. The down and dirty I’m a Blues Man functions as the theme song for the entire album (“I was raised up on Jimmy Reed . . . took my first bath in Muddy Waters”), celebrating the ways that the blues live deep in the singer’s soul with a talking blues underscored by the funked-up guitars, harp, and horns. The soul blues Three into Two Won’t Go sails along on a sea of horns and keys like a tune straight out of Stax. The call and response of the B3 and piano, fueled by Jewel Bass’ and Lah-Lah Devine’s background vocals, turn Cheating in the Next Room into a soulful anthem of a wronged lover whose woman carries on her cheating ways out of sight but not out of hearing of her lover.

Champion finds his way into every song on this album, making it his own, and playing it so we can feel the beauty, pain, and grittiness of the tunes; he lives the blues on Steppin’ In, inviting us to join him as we listen.

—Henry L. Carrigan Jr.

KINGFISH

Kingfish

Alligator Records – ALCD 4990

Alligator Records – ALCD 4990

Many people may not know who Christone Ingram is, but they probably know who “Kingfish” is—his stage presence and sound is impossible to ignore. His mature vocal style ultimately belies his young baby face, while his wicked, wide vibrato betrays his worldly ways around the neck of the guitar. His self-titled debut album, Kingfish, reveals he’s a triple threat as an accomplished instrumentalist, vocalist, and songwriter—he penned two-thirds of the songs gathered here.

Says the 20-year-old bluesman from Clarksdale, Mississippi, “I do think I’m an old soul, that I’ve been here before; I’m moving forward with one foot in the past.” Indeed, his level of self-awareness pretty well sums up the tone of this debut disc. The 12 tracks were recorded in Nashville at Ocean Way Studios (guitar godfather Buddy Guy personally financed the entire recording) and feature a tight rhythm section including drummer/producer Tom Hambridge, rhythm guitarist Rob McNelley, pianist Marty Sammon, and bassist Tommy MacDonald. And oh, yeah—a few surprise guests dropped by to join the party.

The album opens confidently with a hard-grinding shuffle in Outside of This Town—it’s a roadhouse rumbler that served as the first single released as a sign of things to come from this superb CD. Kingfish switches it up quickly with a dripping tempo of Fresh Out, replete with descriptive downtrodden lyrics that has the potential to become a standard in due time. Musical mentor Guy makes a cameo appearance and establishes his presence right from the start. We hear those patented greasy bends that only he can do, and his clean-dirty tone is both unmistakable and immediate as he riffs behind Kingfish’s metaphoric lyrics that describe his empty bed—“no jelly in the jar, no flour in the sack.” The second chorus of Christone’s solo finds the dual guitars blasting on the bent blue note simultaneously until Guy takes off like a rocket and plays the burning lead runs that you’ve been anxiously anticipating. Guy saves his vocal entrance for the last verse, where he sings us all the way to the end of the line. Added together, it’s like listening to a bluesball being alley-ooped from the rookie player Kingfish to the veteran Guy who gets the honor of making the ultimate slam dunk—it’s a wonderful sonic assist.

It Ain’t Right is a joyous Cadillac drive that sounds like it starts in Chicago and ends up in Austin. This hard-drinkin’ shuffle about a mean alley cat of a woman stimulates one of the nastiest, biting blues tones from Kingfish. I love this tune because it’s one of the few that exclusively features the power trio of guitar, bass, and drums (Hambridge and MacDonald, respectively).

On Been Here Before, Kingfish goes acoustic and ditches the drums when he drops into the open E tuning, musically meandering down a dusty road with a slow gait while singing softly the autobiographical lyrics that reflect his personal mantra as he describes his old soul: “I can still here grandma sayin’, ’child, you been here before.”

Chicago stalwart harp blower Billy Branch makes his cameo appearance on the galloping If You Love Me, a tune co-written with mutual keeper-of-the-flame and Taj Mahal protégé Jontavious Willis. Speaking of lineage, legendary guitarist and recent Grammy-winning Mahal collaborator Keb’ Mo’ enters the fray and lends a hand, helping to sustain the tune’s forward momentum.

The slow 6/8 strut that introduces Love Ain’t My Favorite Word features Kingfish’s razor-edged treble tone and stinging vibrato that reveals the significant influence of Albert Collins. This is the tastiest, rawest solo up to this point on the album—and don’t miss the inverted, descending chromatic jazz riff he throws in mid-solo—it’s incredibly unexpected and delicious.

Listen reminds one of the kind of groove that the Tedeschi Trucks Band sometimes favors. It’s also the kind of mellow mood that Keb’ Mo’ can invoke at the drop of a chord, and so it’s such a refreshing confirmation when his throat floats in over Kingfish on the second verse—their two voices blend together like butter and biscuits, baby. Also, the chiming tones of Rob NcNelley’s fingerpicking guitar work really complement this piece.

Before I’m Old is another paean to his inner spirit that seems to be not of its own time. “I was born at the turn of the century . . . grew up way down in Mississippi when I heard Robert Johnson call . . . breakin’ rocks on a chain gang . . . I’ve seen a lot and I’ve done a lot, too young to lay down in that hole; tryin’ to fly and not die before I get old.” Although there are three guitars on this tune, it’s Keb’ Mo’s first solo that grabs your attention—man, he can really burn when he turns up the heat! Kingfish sings one last verse then cranks up his own Fender flamethrower before the exit ramp approaches.

Believe These Blues is a medium-paced, key of A minor blues shuffle with tremoloed guitar chords and a chilling, clear-toned solo that drips all over your ears (Robert Cray instantly comes to mind, who was an absolute master at serving up these specialties.) What a smoldering rocker this one is, with moody, evocative lyrics. “When I see bad things happen to good people everyday, children going hungry with nuthin’ on their plates,” he declares remorsefully, “I believe these blues are never gonna die.” Two tasty solos are emitted from both Keb’ Mo’ and Kingfish.

Trouble takes us right down to Tipitina’s in New Orleans, where Kingfish’s strong vocal delivery sounds so effortless you know the key and vocal register fits right in his wheelhouse. The band really stirs the gumbo pot on this one: Hambridge’s rhumba-rhythm drums, MacDonald’s boogie bass, and Marty Sammon’s “longhaired” piano percolate to perfection. A favorite line of the entire tune was, “She started screamin’ and said, ‘That’s IT!—I ain’t putting up wit’ no more o’ yo . . . TROUBLE!!’” This same instrumentation lays a firm foundation of slow-simmered blues on That’s Fine by Me, which features a short but tasty take by Sammon—the only piano solo on the album.

Hard Times features just the two old souls: Keb’ Mo’ on acoustic resonator guitar and Christone’s Mississippi road-weary vocals. The beauty is, of course, in its melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic simplicity. No drums, bass, or piano needed here—just a coupla glasses of sweet tea and a porch swing will do just fine.

Former Roy Buchanan drummer Tom Hambridge clearly has had the magic touch for quite some time now—witness his steady influence as a creative force that wears many hats, and so comfortably—drummer, producer, engineer, and, most importantly, composer. He’s a self-made man who’s generated a wave of success, leading the way for two Gammy wins for Buddy Guy, not to mention a truckload of chart-topping material for Susan Tedeschi, Johnny Winter, Quinn Sullivan, and several others. Alligator Records owner Bruce Iglauer has done it again—he’s paired a top-notch producer with the heralded arrival of a guitarist who is, by any measure, one of the brightest new stars of his generation. Tell everybody—the Kingfish is here!

—Wayne Goins

WILLIE FARMER

The Man From the Hill

Big Legal Mess – BLM0559

Big Legal Mess – BLM0559

There’s a potently raw kind of blues indigenous to upper Mississippi, a sound that can ride a simple riff to the point of transcendence. Perhaps best epitomized by the recordings of the late R.L. Burnside, and more recently channeled by the likes of the North Mississippi Allstars, it’s primal music, for sure. But what it may lack in poetic sophistication it compensates for in ability to dig a groove as deep and cool as a Hill Country well. The Man From the Hill introduces a previously unrecorded exemplar of that distinctive style in the person of Willie Farmer, a now 63-year-old auto mechanic from the tiny community of Duck Hill (featured in LB #258). Produced in Memphis by Bruce Watson with session support from savvy players such as Jimbo Mathus, Will Sexton, Mark Edgar Stuart, and others, Farmer’s album gloriously reinvigorates the essence of his down-home musical heritage.

As a singer, Farmer, who also plays guitar, often repeats certain phrases like a mantra, appropriately complementing the almost trance-inducing instrumentation. While his wispy tenor may not conform to mainstream standards of excellence, it is an effective voice for this material. For instance, on Break Bad when his high quaver repetitiously intones, “You keep pushing me, baby, ain’t no telling what I’ll do,” it’s ominous and convincing, the melodic utterance of a real man addressing a fundamental reality. And while Farmer often articulates the lyrics in a soft trill, he can also deliver a vocal punch to certain words or syllables with a force that is all the more evident in counterpoint to the gentler tones.

The set list includes four Farmer originals among its ten tracks, the majority of which are high-energy boogies. It kicks off with the loping yet lively Feel So Bad, which bubbles into a sonic stew of fuzzy guitar undulations, pulsing bass, and spare but sprightly drums, all seasoned deliciously by that high wail of his voice. Much of the lyric content occurs in a single line, “Well I’m sorry right now, girl, and I feel so bad,” repeated with variations of phrasing. Other highlights include Shake It, an upbeat shuffle with similar instrumentation and an imperative hook line, “Shake it, baby, shake it,” that recycles with minor changes and verbal additions. Come Back Home rides a smoky and slightly sinister guitar riff amid stream-of-consciousness pleas for a lover to return. Two thematically similar numbers, Fist Full of Dollars and Millionaire, focus on an impoverished persona fixated on money; both tracks rock hard, with the latter also embellished with backing from a female vocalist. The superb I Am the Lightning is a timeless, groove-heavy jam. The title track closes the set with another no-frills boogie ramble in which the singer declares, “I’m the man from the hill. Everybody calls me Mr. Will.”

There are also a few slower-paced songs, such as the aforementioned Break Bad, as well as Daddy Was Right, in which organ accompaniment lurks just behind the vocals and shimmers evocatively during the fills. Moreover, At the Meeting is a gospel sing-along, accented with delightfully quivering guitar licks and multiple voices that collectively imagine a heavenly reunion.

The power of this music is undeniable. By artfully conjuring such sounds, Farmer and his cohort create a conduit to catharsis and even bliss. It’s real-life country blues for the 21st century. As such, The Man From the Hill qualifies as a mighty impressive label debut.

—Roger Wood

KEB’ MO’

Oklahoma

Concord – CRE – 01019

Concord – CRE – 01019

Still basking in the glow of his recent victory with Taj Mahal (he performed on and co-produced 2018’s Grammy Award–winner for Best Contemporary Blues Album, TajMo, bringing his total number of Grammy Awards to four), Keb’ Mo’ continued his winning streak when he cleaned house at the 39th annual Blues Music Awards, where the same album won Album of the Year and Contemporary Blues Album of the Year, and he individually walked away with the award for Contemporary Blues Male Artist of the Year. The tireless blues warrior now releases Oklahoma on Concord Records, with ten intriguing tracks on an album that’s different than any he’s done before—the entire collection was specifically written to address topics such as immigration, depression, pollution, love, female empowerment, and more.

Produced by Colin Linden and co-produced by Keb’ Mo’, to say this was an important project to Keb’ is an understatement. In his own words, “When you are in a certain part of your life, the concept of an album is woven into the process.” Recorded by Zach Allen at Stu Stu Studio, the disc is jam-packed with not only gems but also guests, featuring cameos from Taj Mahal, Rosanne Cash, Robert Randolph, Jaci Velasquez, and Keb’ Mo’s wife, Robbie Brooks Moore.

In the medium-tempo, minor funk tune I Remember You, Mo’ gives us a colorful story about a character whose past includes an estranged daddy who was a hustler. At present, though, this man named Junior weaves this woeful tale while talking to a girl—he last saw her in a red dress in high-heeled shoes and holding a margarita one night at a dance. Past, present, and future scenarios converge in Junior’s soliloquy. No guitar solos involved here, just a good story and a good groove.

Oklahoma, a light-hearted tune Keb’ Mo’ ultimately chose to be the album’s title, instantly becomes a theme song that should be adopted by Oklahomans everywhere. During a visit to the state for a benefit show with guitarist Kenny Wayne Shepherd in 2013, Mo’ witnessed firsthand the remains of a destructive tornado that had just ravaged the community. The piece is laced with empowering lyrics of strength and triumph over turmoil. “Cowboys and Choctaws, Chickasaws and outlaws . . . when the goin’ gets rough, we get tough! Rain or shine, Oklahoma’s gonna be okay!” Robert Randolph, the renowned pedal steel guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter, plays a wicked, haunting lap steel guitar that sounds like someone preaching and crying at the same time—and when he adds the wah-wah pedal to it, the effect is even more powerful.

Keb’ Mo’ asks for a major shift in US political strategy when he penned Put a Woman In Charge, a piece that features guest artist Rosanne Cash on vocals. “Here we are standing on the brink of disaster . . . I know the answer; put a woman in charge—hallelujah!” Upon further review of a time when men invented everything (from fire to the wheel to the automobile), he concludes that a male-dominated world has not paid off. “Call the mothers, call the daughters, we need the sisters of mercy now.”

Contemporary Christian and Latin pop singer-songwriter Jaci Velasquez sings background vocals on This Is My Home, a song about successful immigrants. We first meet Lupi, a woman who’s had a long, hard journey from Mexico, but sent money back home even as she claimed America as the place she belonged. Then a man from Pakistan named Muhammad is finally free—he drove a taxicab for a living, and also claimed the US as his home. The two got together, fell in love, and raised their children. “My people came over from Africa,” Keb’ suddenly chimes in, and, just like the others, “the journey was long.” The statement advocating respect and appreciation for cultural diversity in this country is both powerful and crystal clear: “They sacrificed and they paid the price, so I can live this wonderful life—this is where I belong.”

Taj Mahal plays bass and contributes background vocals on Don’t Throw It Away, a social commentary on raising the level of consciousness about recycling plastic, while warning of the disastrous consequences when cups, bottles, and bags routinely become waste in the ocean that results in the killing of birds, fish, and turtles. “Use it again—don’t throw it away” is the resounding message from the Taj/Mo’ tandem.

The introspective, low-key The Way I is dedicated to a forlorn singer who is trying to hold on to his fractured relationship with his loved one. “I wish that you could love me the way I . . .” (he never finishes his thought) until the last phrase when he finally completes it with “love you.” On the other end of the spectrum, the boogie blues groove heard on Ridin’ On a Train elicits an instant get-out-on-the-dance-floor reaction. It’s a straightforward, simple tune describing the free-wheelin’ spirit of a happy hobo making his way across the country. Keb’s slide work on his acoustic steel Dobro comfortably complements the laid-back lyrics—“I’m feelin’ no pain, I like it like that.”

I Should’ve finds Keb’ as a man who initially has regrets for not staying with various past ladies in his life: “Suzy and Ophelia, and that waitress, should’a married that showgirl, should’a married that trainer . . .” But eventually he turns it around and realizes if he has stayed with any of them, he wouldn’t have the one he loves now. Keb’s storytelling skills rise even higher in his wordplay on Cold Outside, where he senses that another man has been in his house while he was gone. “I thought it was cold outside ’til I walked in here!” he says metaphorically. “I can feel, but I can’t see and I can’t hear; tell me why it’s so cold in here?”

Beautiful Music puts the spotlight on wife Robbie Brooks Moore (might this be the first time he’s featured her voice on his album?). In a moment of humility, humor, and deference, Keb’ Mo’ utters flattering statements: “You’re ‘11’ out of ‘10,’ I might be a ‘2’” and “God made you for me—we make beautiful music together, you’re my song that keeps playing forever.” Indeed, Robbie croons like a songbird, and their voices blend beautifully together whether they sing unison or harmony. It’s a touching way to end the album.

Throughout the entire disc, the music remains poignant, while the lyrics cover a wide range of relevant topics. The project is quite ambitious, but when has Keb’ Mo’ ever done anything that wasn’t personally challenging, purposeful, and thought provoking? This carefully crafted concept album is as beautiful, meaningful, and timely as anything he has ever done, and it comes highly recommended. At the very least, it qualifies him as an Honorary Oklahoman for life and, at most, next year’s repeat Grammy winner for the best that blues/Americana music has to offer.

—Wayne Goins

STEVE HOWELL & JASON WEINHEIMER

FEATURING DAN SUMNER & DAVID DODSON

History Rhymes

Out of the Past – OOTP 0101

Out of the Past – OOTP 0101

Howell, Weinheimer, Sumner, and Dodson make for a formidable quartet, not necessarily in an over-arched way, but rather through their ability to meld their skills while making a supple sound in the process. Comprised mainly of old standards of a vintage variety, History Rhymes finds the foursome hewing to a traditional template while still providing beguiling sort of sentiment in the process. The music that results is a mesh of blues, jazz, folk, and finesse, with each song given an easy, breezy delivery that’s both calming and confident in equal measure.

Most listeners will recognize a good portion of the set list even at the outset, but regardless, offerings such as There’ll Be Some Changes Made, Blues in the Night, Jack of Diamonds, You Don’t Know Me and If I Had My Way take on a casual tone and tempo to sound as fresh as they are familiar. By revisiting these selections from the Great American Songbook in such as wistful way, the group brings new appreciation for the remarkable writers represented—Harold Arlen, Johnny Mercer, Gary Davis, Cindy Walker, Eddy Arnold, Huddie Ledbetter, and Bukka White, among the more notable names. While each of the musicians helps create that cohesion, it’s Howell’s affable vocals and his archtop and flattop guitar play that helps ensure that there’s a sweet sentiment pervading the effort overall.

Ultimately, though, it’s a challenge to single out the standouts. Howell, Weinheimer, and company do such an outstanding job with each of these offerings that the whole album maintains a consistent flow. Nevertheless, the two tracks that cap this collection find these musicians remain passionate purists at heart. A tender take on Lead Belly’s Titanic, which details how Jack Johnson, an African American heavyweight boxing champion, was denied passage on the ill-fated ship, is particularly tender and touching. Likewise, the assertive cover of Bukka White’s country blues classic Pinebluff Arkansas (here as Pine Bluff, Arkansas) is also expressive in an equally engaging way.

Howell’s liner notes offer insights into each song and enhance the appreciation for the entire effort overall. It makes History Rhymes not only a terrific listen, but also a means of gathering lessons well worth learning.

—Lee Zimmerman

MAVIS STAPLES

Live in London

ANTI- – 87652-2

ANTI- – 87652-2

Since the 1950s, Mavis Staples’ powerful songs of freedom, faith, hope, and love have touched hearts and opened minds at home and around the world. The vocalist and civil rights activist has made many seminal gospel, R&B, and soul recordings as a solo artist and with her family group, the Staple Singers, and as she approaches 80 she continues to release timely, deeply moving music. To see her perform live is to see her truly in her element, and her latest album, Live in London, captures two nights (one of which was her birthday) of performances at the British capital’s Union Chapel in 2018.

Dedicated to her late sister Yvonne, the set spans the length of Staples’ career, with most of the tracks spotlighting her records of recent years. Her contralto, always rich and thick, is even more so now, with an extra dose of raw huskiness adding heft and gravity to it. She offers the enthusiastic audience “greetings from the Windy City, Chicago, Illinois—the home of the blues!” and name-checks Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, and her father, Roebuck “Pops” Staples, before launching into the latter’s gospel lament What You Gonna Do. A great stylist, she takes songs like the Talking Heads’ Slippery People (which she first recorded with the Staple Singers in 1984) and Funkadelic’s Can You Get to That (from her 2013 album, One True Vine) and infuses them with soulful, righteous fervor. Her version of Curtis Mayfield’s Let’s Do It Again, a hit for the Staples in 1975, is as passionate and delightful as ever.

Accompanying her on stage are guitarist Rick Holmstrom, bassist Jeff Turmes, drummer Stephen Hodges, and backing singers Donny Gerrard and Vicki Randle. Gerrard’s high, smooth baritone is at times eerily reminiscent of her father’s; Holmstrom’s playing is beautifully needle sharp and precise, embroidering songs like Love and Trust and No Time for Cryin’ with a wide dynamic and stylistic range. Staples drops mentions of “motherless children” and “taking babies away from their mothers” into Cryin’—a pointed reference to America’s current immigration crisis—and urges that “we’ve got work to do.”

It’s remarkable to think that Mavis Staples has been singing for seven decades. It’s even more astonishing that she sings today with undiminished strength and sense of purpose, as Live in London demonstrates. Her voice, and these songs, remain a welcome balm for the soul in troubled times.

—Melanie Young

GEORGE BENSON

Walking to New Orleans: Remembering Chuck Berry and Fats Domino

Provogue Records – PRD75812

Provogue Records – PRD75812

George Benson has found a way to keep things interesting as he adds another chapter to his stellar career. On Walking to New Orleans: Remembering Chuck Berry and Fats Domino, he catches his longtime fans off guard and offers a dual tribute to a pair of rock ’n’ roll legends who roamed the airwaves during the second half of the late ’50s. Chuck Berry is pretty much a world-renowned institution, but when you’re talking Fats Domino, you’re really also talking about Dave Bartholomew, the three-time music hall-of-famer (yet still somehow underappreciated) pioneer who was largely responsible for leading the way out of jump blues/swing and into what became rhythm ’n’ blues / rock ’n’ roll. Indeed, almost every one of the tunes on the “Fats” half of the album was written or co-penned by Bartholomew.

The fun thing about this disc is that almost all the songs clock in at right around four minutes, which reminds us of a time when 45 r.p.m. singles were fairly short and to the point during the days of Fats and Berry. The length of play was formatted not only for radio but also jukeboxes in soda shops, which was a preferred mode of listening for so many teenyboppers.

King George serves up five tracks apiece in honor of each artist, recorded at Ocean Way Studios in Nashville for Provogue Records under the direction of Kevin Shirley who produced, engineered, and mixed the music at the Cave in Malibu, California. Benson is in great company, with a first-tier ensemble cruising underneath him: Greg Morrow on drums; Rob McNelley on rhythm guitar; Kevin McKendree on piano; Alison Prestwood on bass; Lee Thornburg on trumpet; saxophonists Paulie Cerra and Ron Dziubla; and a backing vocal trio of Mahalia Barnes, Natasha Stuart, and Prinnie Stevens.

The album starts with that patented Chuck double-stop riff that opens Nadine (Is It You), a ditty that features several of Berry’s most lyrically genius inventions—just marvel at the way he cleverly contextualizes “mounted cavalier,” “wayward summer breeze,” “coffee-colored Cadillac,” and “southern diplomat.” Oddly enough, as great a composition as it is, the tune was never released on an album, only pressed as a single in February of ’64. George’s version here boasts quite a funkier groove, with a tight, pumping big band blasting behind him—Ron Dziubla’s low, honking bari sax is especially nice against that spicy upper register of McKendree’s piano. Benson quickly cranks out a pair of melodically astute solos, scatting perfectly along with his syncopated, bluesy guitar licks. He swings around one more time after the last verse for yet another chorus of a solo added for good measure—it’s a sure sign that he’s thoroughly enjoying himself.

Ain’t That a Shame is one where you can really hear the fine form that George’s voice is in on this entire album. As for Benson, he takes a seriously soulful solo, delivering another blistering guitar/scatting duo in that inimitable fashion. The aah-oooh’s of the backing female vocal trio really add the right vintage touch to the proceedings. Later in the tune the greasy, growling tenor sax solo of Ron Dziubla lights up a Lockjaw Davis–flavored firecracker that ends the tune on a high note.

At this point in the album, I should say that Ain’t That a Shame and the next track, Rockin’ Chair, are both medium-up-tempo shuffles that sound like Stevie Ray Vaughan’s trio, Double Trouble (Tommy Shannon, Chris Layton, Reese Wynans), would have been totally comfortable backing George on, especially the rollicking piano solo that sounds like Reese walked in the room and sat in! It’s a favorite track on the album because it swings sooo damn hard. Great harmonized horn blasts are added on the chorus from Thornburg, Cerra, and Dziubla. Benson takes a leisurely blues solo that reminds one of Honky Tonk.

You Can’t Catch Me has a driving backbeat with drums slapping hard on two and four, providing propulsive energy beneath the “motor-vating” lyrics detailing Chuck’s humorous “air-mobile” escapades. The original Berry version (featured in the film Rock, Rock, Rock!) was released as a single in 1956 (Chess 1645), and even more significant was the historical event of Chess Records releasing their very first “Long Playing” album, which was, coincidentally, the soundtrack to this movie that featured four singles from Berry’s Chess catalog.

And literally on the other side of that Chess 45 was the one-chord, “cha-cha-cha” vamp of Havana Moon, with a song structure that creates a hypnotic effect, allowing the listener to focus on the descriptive lyrics which tell a tale of Cuban adventures of high winds, a good bottle of rum, and dreams of New York skyscrapers. Meanwhile, Benson does an admirable job of retelling Berry’s travails and even manages to dash off a pretty short-but-sexy solo before the last verse and chorus. Benson was clearly intentional in pairing these two pieces back to back on this album to authentically “replicate” the single as part of the album.

For I Hear You Knocking, the groove has a real swagger-stagger to it—a Texas two-stepper right out of San Antonio, swung low in 6/8 time. George uses a slang-style vocal articulation that fans may have never heard before, which is pretty cool on the ears, and the female backing vocal trio kicks up a notch further. The tune comes complete with a growling Clifford Scott–inspired sax solo by Ron Dziubla taken right out of the pages of Honky Tonk. Meanwhile, Benson takes a sweet and simple solo, as laid back and elegant as a bolo tie.

Memphis, Tennessee is a drum-driven boogie where Benson does the patented double-stop solo almost note for note, then goes it one better with his own percolated single-note jazz inflections that you knew he just couldn’t resist.

Walking to New Orleans has the slow-rolling stroll that finds Benson casually wandering somewhere down Royal Street between St. Louis and Conti. George takes his time delivering the lyrics—no hurry, just let the words do the walking.

Blue Monday finds George with as much vocal sass as he can muster, as he recreates the New Orleans boogie of Domino’s single released in 1956 (Imperial 5417). It’s such a treat to hear the usually erudite, articulate vocal phrasing of Benson traded for the more appropriate, provincial pronunciation as he elocutes, “Sat-a-day moanin’” and “Sun-day moanin’ my head is baad” in his lament about a rough weekend before Monday comes.

The album ends with a relatively lesser-known tune, How You’ve Changed, which finds Benson channeling Berry’s emotions borrowed from the 1958 One Dozen Berrys, his second album for Chess Records. As in Chuck’s original, George’s rendition delivers the tempo down-paced, and the lyrics downtrodden. The good news is that the piano solo is delectable, and Bad Benson’s solo is true blue. Even better is the piano solo that perfectly captures the incomparable touch of Johnnie Johnson. Benson follows up immediately with his own unique tone and touch.

The pacing of the album is excellent—it’s a combination of wise choices of song selection along with smart sequencing of song order. Throughout the set are great horn arrangements by Lee Thornburg. Every song on here is a keeper—Benson has never done anything quite like this one before. He sounds like he’s having more fun than anybody, and at this point in his illustrious career, he can do anything he wants. Sounds like he’s in the mood to go duck walking down to Café Du Monde to get a beignet.

—Wayne Goins

ROSIE FLORES

Simple Case of the Blues

Last Music Company – LMCD206

Last Music Company – LMCD206

When Rosie Flores was a teenager learning chords on the guitar, the first music she played was blues. Over five decades since, the Austin, Texas–based guitarist and singer-songwriter has built a respected career and following with her rockabilly, country, and roots aesthetic. Yet, until now, she had never devoted an entire album to blues. On her latest release, Simple Case of the Blues, she comes full circle musically with a gorgeous collection of songs steeped in traditional blues, R&B, and soul.

Guitarists Charlie Sexton and Kenny Vaughan and bassist Dave Roe are among the musicians joining her in the studio; the trio also serves as the album’s producers. The tracklist mixes originals with compositions by Leiber and Stoller, Wynona Carr, and Wilson Pickett, among others, and Flores and company cast them all in various shades of vintage blues. Jump blues is a natural fit for Flores, as her lively versions of I Want to Do More (originally recorded by Ruth Brown) and Carr’s Till the Well Runs Dry prove. Mercy Fell Like Rain is a stunning gospel blues that hovers somewhere between Saturday night and Sunday morning, mid-century and eternity, and Flores plays and sings with deep conviction. The yearning title track and the sexy roadhouse grind Drive Drive Drive, both written by Flores and Rachel Gladstone, are album highlights. Her smoky, frayed mezzo finds the soul in Dwight Yoakam’s If There Was a Way and wrings every last drop of emotion from Pickett’s If You Need Me.

With its masterful musicianship, production, and classic blues stylings, Rosie Flores’ Simple Case of the Blues is definitely worth catching.

—Melanie Young

HARPDOG BROWN

For Love & Money

Dog House Records – DHR-6902

Dog House Records – DHR-6902

Born in Edmonton, Alberta, Harpdog Brown’s harmonica and vocal work have made him a mainstay of the Canadian blues scene since the early 1980s. He recently discovered that he has family roots that connect him to New Orleans, and For Love & Money brings an acknowledgement of those roots into his musical mix.

The turf that he’s covering here explores the late 1940s / early 1950s borderline between the swing era and the shift to jump blues and the emergence of R&B. So, it’s not surprising that Brown assembles a program that recasts tunes from Louis Jordan (Blue Light Boogie); Amos Milburn (Vicious, Vicious Vodka and Thinkin’ and Drinkin’); Wynonie Harris (Buzzard Luck); and Memphis Slim (The Comeback). His most overt nod to the Big Easy comes on two tracks that feature vocals that clearly derive their sound and style from Louis Armstrong: Brandon Isaak’s swinging original I’ll Make It Up to You and Skye Lambourne’s lilting Sasha’s Lullaby.

Brown keeps that N’Awlins vibe going with his original Stiff, with its growled, funky, Dr. John–like double entendre and sinuous clarinet and bravura trombone solos. Pianist Dave Webb’s title track employs that patented Crescent City R&B piano style riding on a second line groove. The leader’s focus throughout the program is decidedly on his vocals, but he unleashes some impassioned and inventive harmonica work on such tracks as Blue Light Boogie, Buzzard Luck, and Thinkin’ and Drinkin’. Perhaps the most seductive track is Wayne Berezan’s original One Step Forward, an invitation to the dance floor with sizzling brush work from drummer Robert Vail Grant and riffing horns cushioning Brown’s gruff vocals, bringing to mind the 1950s classic The Madison. While Harpdog Brown may have “made his bones” drawing upon the Chicago blues stylings of Sonny Boy Williamson II, For Love & Money shows that he is an artist who can cover a lot of new (and old) ground.

—Robert H. Cataliotti