LEYLA McCALLA

LEYLA McCALLA

The Capitalist Blues

Jazz Village (PIAS) – JV570154

With The Capitalist Blues, Leyla McCalla has vastly expanded her soundscape and taken her music to a whole new level. The first two albums from this banjo player, guitarist and classically trained cellist, Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes (2014) and A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey (2016), were string-band oriented, as she melded folk, blues, Louisiana Creole and Haitian influences. Having lived in New Orleans for almost a decade, McCalla has clearly drawn from the city’s jazz and blues heritage and spirit, incorporating horns, drums and percussion ensembles into her arrangements on The Capitalist Blues and crafting a celebration of the African Diaspora leavened with an unflinching social consciousness.

The ties between Haiti (Saint-Domingue) and New Orleans run deep, and The Capitalist Blues draws upon various musical styles from both locales, as well as from Trinidad and Brazil. The program begins with the title track, recorded at Preservation Hall with some of the city’s top-flight traditional jazz musicians, highlighted by drummer Shannon Powell’s scintillating snare work and emotive solos from banjo player Carl LeBlanc and clarinetist Bruce Brackman. Conjuring the spirits of the city’s blues divas who sang with traditional jazz ensembles—Blue Lu Barker and Billie Pierce—McCalla’s deceptively sensual vocal delivers her critique of greed and inequity. She continues that theme with the calypso classic Money Is King by Trinidadian Neville Marcano, leading the ensemble with her tenor banjo and shaping a perfect groove for the crowded dance floor of a tropical cabaret. The theme carries on, and the tropical beat gets a different variation with Lavi Vye Neg from Kesner “Coupé Cloué” Henry, a master of Haitian “kompa mamba.” With Penha, a Brazilian baião by Luiz Gonzaga, McCalla delivers a prayer for the people to a stripped-down but rocking electric guitar and pandeiro accompaniment.

The tone of the program shifts a bit, and the New Orleans influence shows up again with the original Heavy As Lead, a 1950s-styled R&B ballad featuring powerful, take-it-to-church organ work from Joe Ashlar and a soulful backing chorus led by Topsy Chapman. McCalla’s vocal brings to mind the city’s iconic “Soul Queen” Irma Thomas (and this track begs for a Thomas cover version). McCalla cuts loose with a rollicking love song, Me and My Baby, riding an infectious groove and delivering the simple lyrics with total abandon, an absolutely joyful freedom of expression. The protest singer reemerges on Aleppo. Supported by producer Jimmy Horn’s ferociously snarling electric guitar and Chris Davis’ crashing drums, McCalla chronicles the fear and desperation of that city’s residents. It’s a striking performance that recalls Jimi Hendrix’s Machine Gun, which is a statement that illustrates just how far McCalla has expanded her musical horizons. With Mize Pa Dous, she goes back to the Haitian “twobadou” music she explored on her earlier recordings, infusing it with immediacy by recasting the form with electric guitars. Fiddler Louis Michot and accordion player Corey Ledet come on board for a zydeco/Cajun rocker that features McCalla letting loose with that same freedom and abandon to let her voice ride on a groove. Ain’t No Use harks back to her acoustic string band work and features a blues-tinged, bittersweet vocal that evokes Billie Holiday. The album concludes with Settle Down, as McCalla and guest vocalist Jonas Attis make a final declaration of social protest set to an extended Haitian rara jam with pulsing horns and a sizzling, crackling percussion ensemble. The Capitalist Blues is an incredible musical journey by a stunningly inventive artist.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

JOHN PRIMER

JOHN PRIMER

The Soul of a Blues Man

Blues House – BHP JP2019

Self-produced by John Primer with his wife, Lisa, and Felix Reyes, The Soul of a Blues Man (Primer’s third on Blues House) is an entertaining and personal statement in which he revisits the soul blues set lists of his early-career, bar-gig bands, the Brotherhood and the Maintainers.

John Primer’s significance and prestige as an elder of the Chicago blues scene grows with every passing year. The two-time Grammy-nominated singer and guitarist has been a principal in the bands of Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters (until his 1983 death) and then Magic Slim, until going on his own in 1995. He was a major contributor to the star-studded Muddy Waters 100, and all three Chicago Blues: A Living History CDs for Raisin’ Music. And now, why not a fun project to show how a great Chicago blues band presents the varied faces of Chicago blues and soul, taking the limited instrumentation of a bar band combo (bass, drums, guitar, keyboard, harmonica and one sax) and approximating the fullness of a showband?

Primer accomplishes this with a crew that includes the solid rhythm section of Lenny Media and Chuck-A-Luck on drums and bass, respectively, plus Ronnie Hicks on keyboards, Charlie Kimble on sax and Primer’s main sidekick these days, Steve Bell, on harp. Billy Flynn serves as a perfect dueling partner, guesting on guitar on several tracks. Covered here are three Bobby Bland classics plus Clarence Carter’s Slip Away, Toussaint McCall’s Nothing Takes the Place of You, Lloyd Price’s version of Stagger Lee, Brook Benton’s Rainy Night in Georgia, Johnnie Taylor’s Still Called the Blues and even a Bob Dylan number (by way of Freddie King), Meet Me in the Morning (though no composer credits are provided).

For fans of the classic Chicago “lump” for which John Primer has become rightly famous, the set includes the chugging, straight-ahead Primer originals You Shouldn’t Tell a Lie and Please Don’t Leave Me. A third original, fashioned after the Rice Miller standard Don’t Start Me to Talking, Meet Me in the Park first appeared on Primer’s Cold Blooded Blues Man (Wolf, 1997) as Meet Her in the Dark.

Between Primer and Flynn there is plenty of guitar, including some slide, but the primary focus is on Primer’s deep, impassioned singing, for which these selections provide fine opportunity.

—Justin O’Brien

BENNY TURNER AND CASH McCALL

BENNY TURNER AND CASH McCALL

Going Back Home

Nola Blue – No #

Benny Turner and Cash McCall first met more than six decades ago, when they were performing on the gospel circuit in and around Chicago (see LB #259). Yet, because they each played both guitar and bass, they were never in the same groups together—until now. Spurred by the death of another contemporary, gospel singer Clay Graham of the Pilgrim Jubilees, the New Orleans–based Turner recently reconnected with his old friend McCall, who now lives in Memphis. They decided to make up for lost time by going into the studio together, and on Going Back Home they return to the Chicago blues songs they loved and played in their early days.

Throughout the sessions Turner plays bass (plus guitar on Spoonful and The Dirty Dozens) and McCall rhythm guitar, while they take turns singing lead. Turner duets with daughter Carla Davis on a joyous rendition of Got to Find a Way, his rough-edged soulful baritone matched by her Aretha Franklin–esque soprano. Davis also sings gorgeous backing harmonies on the track with her sisters Benita Turner and Yvette Whittler, and McCall, who played guitar on Harold Burrage’s hit for M-Pac! in 1965, does so again here.

Fellow Chicagoan Willie Dixon’s presence looms large. McCall served a stint in Dixon’s Chicago Blues All-Stars, and he tackles Spoonful with Wolfish gusto and rich tones that defy his recent struggle with lung cancer. Turner likewise roars on the slow-grinding Built for Comfort. Another Windy City compatriot, Billy Branch, contributes lusty lead vocals and harmonica to a loping version of Bring It on Home, which fades out to fun banter between Turner and McCall. Branch’s mournful harp also punctuates the album’s centerpiece and highlight, a rousing cut of Elmore James’ It Hurts Me Too. The only song where Turner and McCall share the vocal mic, their voices brim with true depth of feeling.

That this album was a labor of love is evident from start to finish. The affection Turner and McCall have for each other, combined with their stellar musicianship, makes Going Back Home a truly sweet journey.

—Melanie Young

WILLIE BUCK

WILLIE BUCK

Willie Buck Way

Delmark – DE-857

Octogenarian Willie Buck is now feted as one of the last living links to Chicago’s postwar era, even though he wasn’t actually a major figure during those years. Although he’s known primarily for his versions of classics by the likes of Muddy Waters, here he enhances his set with 12 originals along with a few covers (Crawlin’ King Snake, Blues Before Sunrise, Muddy’s How Deep Is the Ocean and Please Have Mercy) and a fresh offering from guitarist Billy Flynn (Can’t Say Something Good About Me).

In a way, though, “originality” is almost beside the point—whether he’s revitalizing a warhorse or contributing something new, Buck’s music sounds so deeply rooted in the vintage postwar sound that a listener could be forgiven for thinking these tracks were outtakes from some long-lost 1957 Chess session. Harpists Scott Dirks and “Big Spider” Beck channel Little Walter’s spirit like human Ouija boards; pianist Johnny Iguana similarly summons the specters of such past masters as Otis Spann and Sunnyland Slim; the redoubtable Bob Stroger’s bass shuffles and boogies deep in the pocket; guitarists Flynn and Thaddeus Krolicki alternate lead and rhythm with vintage Muddy / Jimmy Rogers / Pat Hare / Guitar Junior panache; drummer Jimmi Mayes shows again that he’s an underlooked Chicago rhythm master.

Buck’s voice has lost some suppleness over the years; his timing, never exactly sure, has gotten stiffer; his lyrics sometimes sound pedestrian. Nonetheless, this company brings out the best he has in him, and aficionados will no doubt appreciate most of what they put forth. Just don’t expect any surprises; music such as this once seethed with militance and aggression, but here it’s treated with a reverence that might seem more appropriate to a recital hall than a juke.

—David Whiteis

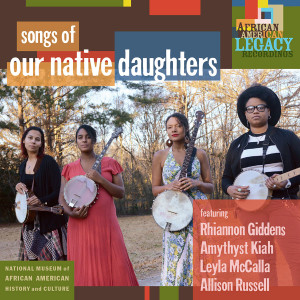

OUR NATIVE DAUGHTERS

OUR NATIVE DAUGHTERS

Songs of Our Native Daughters

Smithsonian Folkways – SFW CD 40232

When Living Blues spoke with Rhiannon Giddens for LB #256, she discussed at length the importance of history and how it informs the multi-instrumentalist and singer-songwriter’s work. “I feel like my job is not really so much writing, ‘Hey, everybody! This is happening and it sucks!’ It’s more like, ‘This is what happened. Can we see how this is still happening? Can we connect to these stories in a way that makes you care about what’s going on right now?’” Listeners can trace this sense of purpose throughout Giddens’ career, but it has perhaps never been as fully realized as on her latest project. Giddens invited Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla and Allison Russell to collaborate with her and co-producer Dirk Powell on what would become Songs of Our Native Daughters, a powerful collection of songs inspired by the narratives and experiences of enslaved African American women.

Drawing on historical texts and melodies, the Daughters brilliantly connect the stories of black women across time to the present moment. Kiah’s strong alto voice on the rocking Black Myself recalls the richness and authority of Nina Simone, while her unsparing lyrics reference racism, colorism and slavery: “Is you warshed in the blood of your chattel? / ’Cause the lamb’s rotted away / When they stopped shipping workhorses / You bred your own anyway.” The blood-curdling a cappella Mama’s Cryin’ Long, written by Giddens, views a lynching through the eyes and words of a child. After learning the name of her family’s enslaved ancestor, Russell wrote the haunting Quasheba, Quasheba as a way to honor her—“By the grace of your strength / We are home.” Through the horrors the Daughters also manifest themes of resistance, survival and hope, exquisitely limned on songs such as Moon Meets the Sun, I Knew I Could Fly, Music and Joy and You’re Not Alone.

Banjoists and roots musicians all, they bring a variety of musical forms to the table, from a reimagined minstrel banjo tune on Giddens’ Better Git Yer Learnin’ to Haitian folk on McCalla’s enchantingly lovely Lavi Difisil. The central melody of Barbados is considered the oldest western notation of slave music in the New World. Bookending the muted, forboding instrumental are two spoken-word passages read by Giddens—a satirical poem by William Cowper and a modern update by Powell calling out society’s complicity in slavery, then and now.

These songs are equal parts beautiful, harrowing and necessary. With its centering of black women’s art and voices, Songs of Our Native Daughters provides an important American historical and musical correction.

—Melanie Young

GARY CLARK JR.

GARY CLARK JR.

This Land

Warner Bros. Records – 584802-2

Gary Clark Jr. is no stranger to racism—the Texas guitarist and singer-songwriter has admittedly and unfortunately dealt with it his entire life. Yet, a recent ugly, racist confrontation with a neighbor who didn’t believe Clark was the landowner of his 50-acre ranch near Austin especially infuriated him. Coupled with the turbulent American political atmosphere in the wake of Donald Trump’s election, Clark felt like he needed to address what was happening to and around him in his art. He does this and more on his new release, This Land, letting loose lyrically and musically on his most expansive, brilliant set to date.

The title track opens the album like a volcano, with Clark pulling no punches with a hip-hop beat and molten streams of sound from his guitar. Incandescent with righteous fury at those who hate and discriminate against him, he snarls, “Fuck you, I’m America’s son / This is where I come from / This land is mine.” One can’t help but think of Woody Guthrie’s This Land Is Your Land while listening—indeed, he has a songwriting credit on This Land—and believe that Guthrie would wholeheartedly approve. The horn-backed, hard R&B of Got to Get Up calls for resistance, while Feed the Babies nods to the socially conscious soul of Curtis Mayfield and Marvin Gaye.

Clark also branches out sonically on this album, swirling together a kaleidoscope of blues-based genres and sounds. His high vocals and lush, torrential arrangements on I Walk Alone and Pearl Cadillac evoke Prince; this feel is bolstered by the presence of the late rocker’s percussionist Sheila E. on several tracks. Gotta Get Into Something careens with breakneck punk energy, while Link Wray–esque guitar licks caress the retro-soul love song When I’m Gone. His resonant slide playing on The Governor and deeply felt singing and solo picking on Dirty Dishes Blues bring him around full circle to the blues.

“Something’s going on with me / I’m not who I used to be, no,” Clark declares on the heavy-rocking anthem Low Down Rolling Stone. On This Land, he has artistically put himself out there in a way he hasn’t before, and it’s a brave move for him to make. It’s also resulted in his finest work yet.

—Melanie Young

KENNY “BEEDY EYES” SMITH & THE HOUSE BUMPERS

KENNY “BEEDY EYES” SMITH & THE HOUSE BUMPERS

Drop the Hammer

Big Eye – BE-0005

Drummer Kenny Smith (son of Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, one of Muddy Waters’ most legendary drummers) obviously takes legacy seriously. On this, his long-awaited debut as a leader, his cohorts are several other noted blues torchbearers, including guitarists Greg Guy (Buddy’s son) and Guy King (disciple of the late bassist Willie Kent), harpists Sugar Blue (whose mentors included James Cotton, Big Walter Horton and other postwar legends) and Omar Coleman (one of Chicago’s relatively few younger-generation blues harpmen) and, on the affectionately cutesy Hey Daddy, his own children (Mae, Clara and Teddy Smith). The rest of the House Bumpers likewise contribute a bracing meld of old-school blues fervor and forward-looking musical elan.

Smith, known mostly as a dedicated roots man, stretches out here; the set includes everything from the expected straightforward shuffles through mystery-tinged, acoustic Delta evocations (the opening Head Pounder) to rock-flavored crunch blues (the title tune) and torrid funk-rock-blues fusion (Puppet on a String, on which Smith jubilantly gets his Ginger Baker on). He also reveals himself to be an expressive singer, with a grainy timbre and an emotional range that extends deeper and wider, and can plumb depths much darker and more ominous, than some might have expected. Special kudos should go to back-up vocalists Kimberly Johnson, Andrea Miologos and Dana Gordon, whose fusion of churchy fervor, sexy innuendo and take-no-mess feistiness add both texture and vivacity.

Kenny Smith remains a first-call drummer for traditionalists/revivalists who want to anoint themselves with the imprimatur of “authenticity,” but on his own—as he demonstrates here—he’s a forward-looking artist, abrim with ideas and girded with the courage to explore new and challenging directions. One gets the feeling that this is the beginning of an important musical journey for a young man poised to make a name for himself as a full-fledged contemporary blues innovator.

—David Whiteis

COLIN LINDEN & LUTHER DICKINSON WITH THE TENNESSEE VALENTINES

COLIN LINDEN & LUTHER DICKINSON WITH THE TENNESSEE VALENTINES

AMOUR

Stony Plain – SPCD 1405

The program that Colin Linden and Luther Dickinson have put together for Amour could easily be subtitled “Love Americana Style,” as they draw upon vintage love songs from blues, R&B, country and folk. The project seems largely Linden’s undertaking as he partners up with Dickinson for the guitar work but handles the production duties and assembles a backing band and guest artists from the Nashville music scene, where he has taken up residence to oversee the music for the Nashville television series. The Tennessee Valentines include bassist Dominic Davis, drummer Bryan Owings, keyboard player Kevin McKendree and violinist and accordion player Fats Kaplin.

Opening with an instrumental version of Careless Love, featuring the two guitarists in a spicy dialogue of stinging electric lines, seemingly promises a guitar pyrotechnics affair. That is not the case. What follows is a focus on guest contemporary vocalists (with one exception) delivering heartfelt recastings of classic love songs. Nevertheless, with Linden and Dickinson at the helm, there are plenty of hot guitar licks to spice things up. Linden handles lead vocals on two R&B numbers, the Jesse Stone–penned, Roy Hamilton hit Don’t Let Go and the Bo Diddley B-side Dearest Darling. He’s an emotive singer who is able to infuse just enough grit into these numbers to make them stand up to the originals. And, the twin guitarists engage in grinding, bluesy exchanges that ramp up the funk factor on both tracks.

The lineup of guest vocalists includes Linden’s fellow Canadian Rachael Davis for two tracks, Jimmy Reed’s Honest I Do and a return to Careless Love. Ghanaian Ruby Amanfu steps to the mic on Kris Kristofferson’s For the Good Times and the Chuck Willis R&B hit What Am I Living For. Linden recruited two cast members from Nashville, Sam Palladio for Ray Price’s Crazy Arms and Jonathan Jackson for the Elvis Presley B-side I Forgot to Remember to Forget. The program is rounded out with a veteran Music City singer-songwriter Billy Swan for a remake of his Lover Please, a 1962 hit for Clyde McPhatter. Linden and Dickinson deliver a wide range of stylistic approaches to the vintage material; highlights include the Cajun flavor that spices up Swan’s number; a loping shuffle with a ringing electric dialogue on Davis’ take on Reed; and Amanfu clearly evoking Al Green with her softly purring approach to the Kristofferson tune. Amour illustrates the creative payoff that results when you give players like Colin Linden and Luther Dickinson the freedom to explore the roots music that provided them with their initial inspiration to become music makers.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

MARY LANE

MARY LANE

Travelin’ Woman

Women of the Blues – No #

Mary Lane was born in Clarendon, Arkansas, in 1935 and had already sung with the likes of Joe Hill Louis and Robert Nighthawk before moving north to Chicago in 1957. Although she has been a fixture on that city’s blues scene ever since and is a member of its Blues Hall of Fame, she has recorded too seldom, beginning with a mid-’60s single as Little Mary for Friendly Five, fronting her then-partner Morris Pejoe’s band, followed by three tracks on a 1987 Wolf anthology, the fine and well-received CD Appointment With the Blues for Noir in 1996 and six titles from 2016 that were issued on West Tone’s Chicago / The Blues Legends / Today! last year.

Now, at age 83, Lane is finally getting the attention she deserves with the release of this CD on Lynn Orman Weiss’ newly launched Women of the Blues label and Jessica Ynez Simmons’ DVD I Can Only Be Mary Lane, which documents the creation of the new CD. The sessions were produced, engineered and mixed by Grammy Award–winner Jim Tullio, who also played guitar and bass on most tracks and contributed to writing all but one of the songs on the all-original, ten-song playlist. The program kicks off with the autobiographical title track, which is taken at an easy-walking tempo that lets Lane put her song across with none of the histrionics that mar the work of too many other vocalists—perhaps it is Lane’s emphasis on telling her story that led fellow octogenarian Bobby Rush to exclaim, according to the notes, that “she sounds more like 33 than 83.”

The preference for medium to medium-up grooves extends to all but two of the selections: the soulful ballad Let Me Into Your Heart, with Chris Cameron contributing the churchy organ and piano and Simbryt Dortch helping out on the vocal, and the closer, Make Up Your Mind, which finds Lane accompanied only by Colin Linden’s Delta-soaked acoustic guitar stylings that leave the listener wishing for more. Although seven other guitarists—including Sam Butler, Shedrick Davis and Dave Specter— pitch in alongside Tullio on the other tracks, none of the combinations quite achieves the level of empathy attained by Johnny B. Moore and Robert Mell on the Noir set. Other guests include Eddie Shaw, Billy Branch, Corky Siegel and Rice Miller disciple, Brazil-native Indiara Sfair on harmonica, and Gene Barge on tenor sax, for one song each.

If there’s a complaint here, it’s the LP-like running time of only 38:54. That’s plenty, though, to confirm that Mary Lane is a lady who says what she means and means what she says—when she tells her man he better leave that wine alone, he best take heed. If you’re looking for an album of honest, heartfelt blues, you can’t go wrong with Mary Lane.

—Jim DeKoster

IKE COSSE

IKE COSSE

Don’t Give Up on Love

Lula B. Records – No #

Ike Cosse has been at it for more than a few years, hitting up clubs in the San Francisco Bay Area with his band, the Coldbloods. After releasing his music on his own label, he was picked up by JSP for a pair of releases, The Lowdown Throwdown (1997) and Cold Blooded World (2000), but that was about 20 years ago. With titles like Bang Bang Girls, Hubba Bubba Brother and Dog Dang Shoot, it doesn’t take long to figure out that he isn’t an artist who takes himself too seriously, and, if you attended any of his shows, you’d know for sure he is serious about having fun while making his audience laugh and feel good.

His most recent recording, Don’t Give Up on Love, follows in that same vein, with 14 jump blues tunes, shuffles, ballads and heart-broken lyrics that are light on the ears and heavy on the humor. Ike performs quadruple duty on this affair—he sings and plays guitar, bass and harmonica. Jimmy Goings plays percussion, and Cameron Nuessman plays organ and percussion on a couple of tunes. These two also produced and engineered the album for Cosse.

A bona fide lefty guitarist (not an upside-down righty with strings in reverse), Ike has a pretty healthy dose of talking phrases in his singing, and he is more interested in telling a good story than singing with polish and precision. Friends With Benefits serves as a talking blues that matches this description, as does The Love You Took Away. The latter includes tongue-in-cheek lyrics and features his harmonica skills in lieu of his guitar work (there’s a reggae version included on track 13 of the disc). The blues shuffle 12 Steps Blues has humor scattered throughout, including the line: “She put herself in ‘12 Steps,’ I said, ‘You need 13!’”

Things slow down with Memo Blues where Cosse sings well-constructed lyrics while demonstrating a razor-sharp lead guitar tone reminiscent of some of B.B. King’s early Modern recordings, simultaneously pulling off a few nifty riffs that land somewhere between Buddy Guy’s boundless bends and the chicken-pickin’ phrases of Albert Collins.

The title track, Don’t Give Up on Love, has a Memphis-flavored, Stax Records kinda groove and chord progression, while his lyrics are reminiscent of something that might come from Robert Cray. Cosse’s vocals are not nearly as strong as some other blues singers, but overall it’s a pretty smooth tune, and his singing style fits his writing style quite well. It’s Been a Long Long Time also falls in this same category and description. A welcome change of pace occurs with the medium-slow Mexicali groove in a minor key, Paso Robles Blues, about a romance with a “senorita named Lolita.” The last track of the album is an extended instrumental version of the song that features a tasty guitar solo from Ike.

Cosse overdubbed many of the rhythm section parts by and for himself, which means that he has, by default, a pretty sturdy backing band that hangs with him at every turn. This actually makes the entire album even more enjoyable. The two-step Texas lope of Crocodile Tears and Have You Seen My Baby have humorous lyrics scattered throughout and tunes that would go over really well at any juke joint, as well as any outdoor summer blues festival.

Ike Cosse is a multi-talented player who knows what his strengths and weaknesses are and unabashedly exercises his musical skills in the niche he has created for himself—he deserves a nod and a listen just for that.

—Wayne Goins