ROBERT FINLEY

Goin’ Platinum!

Easy Eye – No #

Singer/guitarist Robert Finley was already in his 60s when Tim Duffy of the Music Maker Relief Foundation found him playing on the streets in Helena, Arkansas, during the 2015 King Biscuit Blues Festival. That chance encounter resulted in Finley’s 2016 album, Age Don’t Mean a Thing, on which he showcased his grizzled-sounding but resonant baritone voice and dexterous fretboard chops on fare ranging from deep 12-bar blues through soul ballads to propulsive, R&B/pop-flavored flag-wavers. Seldom has the sobriquet “soul blues” been more appropriate, even though Finley’s sound is gutsier and more clearly rooted in tradition than that of most contemporary artists who are usually described that way.

All of the songs here were written or co-written by producer and label owner Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys (his collaborators at various points include John Prine and Nick Lowe, among others); the storytelling is eloquent throughout, atmospheric and evocative without descending into bathos or cliché. Finley’s vocals, meanwhile, are more than up to the lyrics’ challenge: he can evoke passion, mystery, erotic tension, jubilation, outrage and spiritual yearning with equal aplomb, all the while avoiding histrionics or overkill. The songs themselves connect with straight-ahead blues, soul, R&B, folk pop and rock ’n’ roll, replete with tantalizing and obscure references (the set’s opener, Get It While You Can, for instance, summons echoes of the Stones’ 19th Nervous Breakdown) and enough chordal, melodic and harmonic swerves to please musically adventurous listeners, even as they remain sufficiently straight-ahead to be attractive to more roots-minded aficionados.

It’s difficult to imagine how an artist with gifts as vast and varied as Robert Finley’s could have remained under the radar for as long as he did, but his emergence over the last few years is cause for celebration.

—David Whiteis

SWEET PEA ATKINSON

Get What You Deserve

Blue Note – B002717002

Hillard “Sweet Pea” Atkinson was born in Detroit in 1945 and came of musical age under the influence of the Dells’ Marvin Junior and the Temptations’ Paul Williams. He got his break when the multi-talented Don Was of Was (Not Was) / Orquestra Was fame heard him singing at a Motor City union hall in the late ’70s and took him on as the band’s principal vocalist. In addition to his collaborations with Was, Atkinson became involved in the Boneshakers with guitarist Randy Jacobs and worked extensively as a backing vocalist, most notably with Lyle Lovett. Although he was featured to good effect on albums such as Orquestra Was’ Forever’s a Long, Long Time and the Boneshakers’ Book of Spells, his only previous outing under his own name was Don’t Walk Away, which was produced by Was for Island in 1983.

Was, of course, is now president of the venerable Blue Note label and has taken advantage of that position to return his old bandmate to the spotlight. Was himself produced three of the set’s ten tracks, dipping into the 1960s soul bag for Freddie Scott’s Are You Lonely For Me, Baby and Am I Grooving You and resurrecting the J.B.’s 1973 funk chant You Can Have Watergate Just Gimme Some Bucks and I’ll Be Straight, with Boneshakers’ associate Mindi Abair’s tenor sax taking the Maceo Parker role. The balance of the program was produced by Keb’ Mo’, who brought his own Slow Down and Just Lookin’ to the session, along with offerings from the songbooks of Bobby Bland, Johnnie Taylor, Bobby Womack and the Temptations, and the title track from Jerry “Wyzard” Seay of the Atlanta-based funk rock aggregation Mother’s Finest, where Atkinson trades verses with Vida Simon and Wyzard himself contributes acoustic guitar, keyboards, bass and drums. Elsewhere, accompanists include Keb’ Mo’ and Jacobs on guitar, with such A-list session men as saxophonist Joe Sublett, bassist Reggie McBride and drummer James Gadson.

As for Atkinson, he still sports the snap-brim fedora, dour countenance and gravelly vocals that make one wonder how he came by his stage name—and wonder even more how he could have gone 35 years between albums. Happily, Atkinson is still on top of his game, and you can file this one, along with the recent comeback albums by William Bell and Don Bryant, among the must-haves for connoisseurs of the classic sounds of soul.

—Jim DeKoster

HENRY GRAY & THE CREOLE CATS

92

MusicMatters Records – 1191925

At age 92, pianist and singer Henry Gray is still going strong after seven decades of living the blues life. A Louisiana native, Gray first made his mark in the blues world when he relocated to Chicago after his military service in World War II, most famously as the pianist in Howlin’ Wolf’s band for 14 years. Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed and Little Walter are among the many other stars he supported during his tenure in the Windy City. He returned to Louisiana in 1968 and has performed regularly in his home state and toured nationally and internationally over the subsequent five decades! His vitality as an artist is certainly evident in his appearance in the 2015 documentary I Am the Blues.

Gray first met zydeco musician Terrance Simien at the 1984 New Orleans World’s Fair, when he was 59 and the up-and-coming zydeco star was 19. When their paths crossed again recently, Simien was compelled to document the older musician’s remarkable musical durability. He plays washboard and leads the band, the Creole Cats—Paul “Lil Buck” Sinegal on guitar, Bob Corritore on harmonica, Danny Williams on organ, Stan Chambers on bass and Oreun Joubert on drums—that he put together to support Gray on 92.

The album captures Gray doing what he does best—playing rocking, postwar, urban, Chicago-style blues with a dash of Louisiana spice. The pianist shows off his prodigious boogie-woogie skills on the original instrumental Henry’s House Rocker. Gray pays homage to a mentor from his early days in Chicago on Big Maceo Merriweather’s Worried Life Blues, which features a stinging lead guitar from Sinegal and surging harmonica and organ fills that support Gray’s piano wizardry from Corritore and Williams. While time has taken some toll on Gray’s vocals, he remains an emotive and spirited singer, and is particularly effective on the classic Stagger Lee and the fitting original Blues Won’t Let Me Take My Rest. On one track Simien interviews the elder statesman, getting him to discuss his formative years when his father urged him to play gospel, which he illustrates with Thomas Dorsey’s Lord Will Make a Way Some How, and his attraction to the blues with a solo rendition of Blues Won’t Let Me Take My Rest. The program concludes with Simien narrating Gray’s life story to the elder statesman’s rollicking solo accompaniment. With 92, Henry Gray is a living testimony to poet Al Young’s assertion that “the blues don’t bruise / they only renew.”

—Robert H. Cataliotti

CURTIS SALGADO AND ALAN HAGER

Rough Cut

Alligator Records – ALCD 4980

After basking in the glow of the 2016 multiple award-winning album, The Beautiful Lowdown, Curtis Salgado has found a way to shake things up a little by sharing the spotlight with his longtime blues cohort, virtuoso guitarist Alan Hager for his newest venture, Rough Cut. Portland-born guitarist Hager and Eugene-based blues harp ace Salgado have traveled together in similar circles since 2003 and performed as a duo since 2008, when they formally joined forces in 2015 and Hager became the lead guitarist for Salgado’s band. “One reason I made this record was to show him off,” Curtis proudly announced. Indeed, this Alligator Records release successfully combines the talent of both Oregonians, who penned six originals balanced with a healthy dose of well-executed covers, augmented by a supporting cast of guest artists scattered across 13 tracks.

I Will Not Surrender is the opening track that has real meaning for Salgado—the song laments his will to find the strength to overcoming the darkness that accompanies so many funerals of his loved ones. Delivered as an unrehearsed, one-take solo feature, the slow-drip, minor blues drone finds Curtis delivering potent lyrics over Hager’s conjuring of John Lee Hooker– style guitar riffs laced with tremolo and reverb drenched over Skip James, Little Son Jackson and Charlie Patton’s souls—you can feel the cold in the lady’s casket.

So Near to Nowhere showcases Salgado’s chugging and wailing harmonica technique as he unfurls the doomsday refrain, “Tomorrow who knows, tonight who cares? It feels like I’m next to nothin’, so near to nowhere…” Curtis follows the evocative chorus with a short but bursting blues harp solo, with Alan spitting out crystalline acoustic chord changes underneath.

One Night Only features guest appearances of Jimi Bott on drums and Jim Pugh on piano as they join in for a medium-tempo juke joint shuffle. There’s no bass, which makes it all the better—the tune breathes so much better with the boogie-woogie groove in Pugh’s left hand. The already-familiar fan favorite I Want My Dog to Live Longer (The Greatest Wish) again reveals Alan’s mastery of Big Bill Broonzy’s guitar technique and Curtis’s gritty vocals in the touching ode to man’s best friend.

After these first four original pieces, the duo dips into the well-established blues canon. I Can’t Be Satisfied is a beautiful and precise rendition of Muddy’s tune. Augmented with Russ Kleiner’s snappy snare brushes on drums and Keith Brush’s thumpy doghouse bass line, Salgado’s well-executed vocals flow seamlessly over the sinewy slide licks from Hager.

On Too Young to Die, Hager literally plays two guitar parts at once (walking bass line and chord progression!) while Salgado masters the tremolo-laden voice of Sonny Boy II along with the patented riffs on harp to match. This is followed by an excellent replication of Son House’s quivering vocal style on Depot Blues, which is a real treat—supported by the absolutely great finger-picking technique on Alan’s acoustic guitar. We then suddenly find ourselves in Sunday church service with Morning Train. You’ll get good religion when you hear this one, as LaRhonda Steele’s backing vocals and Brian Foxworth’s drums are added to full effect to propel the gritty Salgado lead vocals and great slide playing of Hager—Pops Staples would have appreciated this good ol’ fashioned gospel revival.

Brush’s bass and Kleiner’s drums lend a hand on as Curtis and Alan do serious justice to the Elmore James version of You Got to Move (from the 1966 posthumous release, I Need You.) Salgado captures all the subtle vocal nuance of Elmore, while Hager does the electric slide with glee.

Salgado unveils another original tune with Hell in a Handbasket, a solo performance with Curtis demonstrating the barrelhouse piano playing technique very much in the style of Kansas city pianist Jay McShann—check out the way he rolls off those descending right-hand blues riffs so effortlessly, with delightfully descriptive lyrics throughout the storytelling vocal approach.

We finally hear Hager’s virtuosity on the Robert Wilkins 1929 classic Long Train Blues—he delivers a stellar vocal performance, as he accompanies himself with his other-worldly “Piedmont-meets-Patton” style of fingerpicking guitar, while Curtis strides alongside him with percolating harp jabs—it’s one of the best tracks on the entire disc.

The Gift of Robert Charles, a Hager-penned original (named after his beloved father), leads with a slow instrumental where he plays slide and fingerpicks simultaneously, and it is stunningly beautiful. He then shifts uptempo into a galloping pace with a touch that would make Chet Atkins blush. Hager casually flaunts such great technique, replete with chiming harmonics thrown in at the end of phrases for good measure. The album closes with an acoustic trio performance of Broonzy’s I Want You By My Side—keeping true to the Jazz Gillum version, Curtis offers mellow vocals with high-pitched harmonica, Brush’s acoustic bass, and Alan’s acoustic guitar.

This excellent balance of Pre-War blues standards and originals works extremely well, and compliments go to Johnny Lee Schell, who did an excellent job mixing the album—it sounds superb. “We did it for the love of the music,” Salgado was quoted as saying. “This is where are hearts are.” Indeed, this is American Classical music at its finest.

—Wayne Goins

BEN HARPER & CHARLIE MUSSELWHITE

No Mercy in This Land

Anti- – 87561-1

When Ben Harper and Charlie Musselwhite met up in the studio in 2013 to record Get Up!, they hardly expected that it would win a Grammy for Best Blues Album in 2014. The pair first met when John Lee Hooker brought them into the studio to play on the song Burnin’ Hell. Harper and Musselwhite discovered then a groove, a similar love for the blues—and for searching for old records in dusty record bins—and passion for digging deep into the soul of a tune.

No Mercy in This Land showcases the deep-in-the-blues partnership that Harper and Musselwhite continue to develop. Harper masterfully commands a vocal range that soars from blues moan to soul-stirring shouts, and Musselwhite bends and blows his harp as he weaves mournful phrases into some tunes and jumping and joyous trills into others. Harper’s blues moans in the first four bars of the album’s opening song, When I Go, move slowly into a classic, slow-burning tune of loss and the things you leave behind and the things you take with you in order to survive. Bad Habits is a bright jump blues tune that delivers a down-and-out theme of the unraveling of love; the singer cries at least once a day, declaring that his lover, or his bad habit, is “like a puzzle in a box / but I’m the one coming all apart.” A classic soul song, Love and Trust, recalls the best of Curtis Mayfield and Mavis Staples. With its Muddy Waters vibe, The Bottle Wins Again, which may be the best song on the album, masks its message about the mixed joys and anguish of drinking in a shimmering, shouting tune. A gospel piano opens the ballad When Love Is Not Enough, which recalls the Stones’ I Got the Blues from Sticky Fingers, and Harper’s just-right phrasing reveals the aching, regretful feeling of the song. The title track features Musselwhite’s gravelly vocals in a song that could almost be an anthem for today’s troubled times: “What would be the first thing you would say to the Lord / won’t you please help me to understand / is there no mercy in this land?” Yet, at the very end of the song, the music stops for a moment as Musselwhite asks plaintively whether or not mercy exists for his murdered mother, buried beneath the headstone at which he gazes.

Harper and Musselwhite sound as if they’ve been playing together for a lifetime; the songwriting and playing set No Mercy in This Land in a category by itself, and it’s not too early to say that this is one of the best albums of the year.

—Henry L. Carrigan Jr.

RONNIE EARL & THE BROADCASTERS

The Luckiest Man

Stony Plain – 1396

Over 50 years into a sterling guitar career, Ronnie Earl, a name he took as a tribute to Earl Hooker, shows no signs of a letup on his new release, The Luckiest Man. He’s been part of many high-caliber lineups and this one is no exception. The listener hears every note of Earl’s crisp guitar. All songs are slow to mid-range in tempo, with superb intertwinings with keyboardist Dave Limina. Drummer Forrest Padgett and bassist Paul Kochanski provide a solid foundation.

Boston’s Diane Blue handles vocals on six songs beautifully. On Never Gonna Break My Faith, she goes to the gospel side of the tracks with a prayer for souls lost before their time. On Death Don’t Have No Mercy, a Gary Davis classic, Blue plaintively sings, “Death don’t have no mercy in this land / It’ll come to your house and it won’t stay long / You look in the bed and somebody be gone.” On Heartbreak she laments losing her baby, singing, “If I was a judge / I’d send him to the chair / I’d sit right down beside him / And he wouldn’t leave me here.”

Early on, Earl played with Otis Rush and here he remembers him with Rush’s anthemic So Many Roads. “So many roads, so many trains to ride” is a line that never gets old. This is one of two songs that clock in at over ten minutes in length.

There are five instrumentals on this CD, with Jim’s Song and Sweet Miss Vee being slow and dreamy with a special sweetness.

On Long Lost Conversation, Earl rejoins his old band the Blue Tones including the track’s songwriter, Sugar Ray Norcia, on vocals and harp. Mike Welch adds guitar, and Anthony Geraci plays piano. It’s a “late night hour, sittin’ alone on my bed, dreaming of a long-lost memory” sort of song.

There are many landmarks on Earl’s train. On his first record he played slide to Sunnyland Slim’s piano; he played with Muddy Waters in 1979; in 1988, after eight years with Roomful of Blues, he formed the Broadcasters; and since then, he’s won three Blues Music Awards.

Earl once stated that the purpose of the Broadcasters is to broadcast peace, hope, good vibrations and soul. The Luckiest Man adds to that purpose.

—Robert Feuer

R.L. BOYCE

Roll and Tumble

Waxploitation – No #

A veteran of R.L. Burnside, Jessie Mae Hemphill and Otha Turner’s bands, guitarist and drummer R.L. Boyce is a bona-fide Hill Country elder. Though Roll and Tumble is the Como, Mississippi, native’s second album (his solo debut was 2007’s Ain’t the Man’s Alright), it’s notable for a couple of firsts—the first blues release from the Waxploitation label and earning Boyce his first Grammy Award nomination in the Best Traditional Blues Album category.

Luther Dickinson and David Katznelson co-produced Roll and Tumble, and Dickinson plays guitar along with Boyce and Lightnin’ Malcolm. Father and son drummers Calvin Jackson and Cedric Burnside also join in, with bass drummer Andre Otha Turner rounding out the ensemble. Sinuous, mesmeric grooves permeate these songs, as does a laidback, jovial atmosphere. Recorded on Boyce’s porch and at the Dickinsons’ Zebra Ranch studio, easy laughter and banter are scattered throughout, and together with the ambient noise this lends an intimate feel and presence to the sessions.

Boyce’s vocals and playing style naturally bear the influence of his peers and mentors, and he’s a joy to listen to here, full of high spirits. The musicians cleave closely together, letting Boyce take center stage and following wherever he leads them. His mournful, a cappella singing of the opening line of the title track is especially arresting. Along with his versions of this and R.L. Burnside’s Poor Black Mattie and Going Down South, there are seven songs credited to Boyce. A highlight is Which R.L. Do You Want, in which he briefly encapsulates his life in music. His turns of phrase can be funny and biting; on the moody, slow grind Don’t Worry My Mind he declares that when he dies he’s going to go out “with my ass in the air”: “Don’t come to my funeral and think you’re gonna look at my face / You won’t see nothing but ass and nuts.”

Hopefully that’s something he won’t have to worry about for a long time. Lively and entrancing, R.L. Boyce’s Roll and Tumble is a prime addition to the Hill Country canon, and should bring him to a new, wider audience.

—Melanie Young

HAMILTON LOOMIS

Basics

Ham-Bone Records – HBR109CD

Since the release of Hamilton Loomis’ last album, 2013’s Give It Back, the Texas blues-rocker became the father of a baby boy. That joy was tempered when Bo Jordan Loomis was diagnosed with congenital hyperinsulinism at age one, a rare condition in which the pancreas overproduces insulin, causing blood sugar to drop dangerously low. His son is thankfully doing well, and Loomis has channeled his focus and gratitude into Basics, a new collection of songs pulsing with positivity and high energy.

Loomis’ blend of Texas blues, rock and funk, honed from his days of playing with artists such as Johnny Copeland, Bo Diddley and Joe Hughes, has a more refined, organic feel. With lyrics like, “I need an injection of your sweet affection,” the flirtatious rocker Sugar Baby nods to the reason Loomis wrote it—as a thank-you to the organization Congenital Hyperinsulinism International, which works to improve the lives of those affected by the rare disease. Other tracks, such as the earnest Reason, Getting So Big and Prayer, reflect a new father’s love, wonder and hope. His guitar soloing is as fiery and intense as ever, especially on cuts like Ain’t What It Ain’t, Come and Get Me and Love Can Do. Loomis’ desire to give back has also led him to mentor young musicians in and around Houston, and at the end of Funky Little Brother there’s a brief, fun instrumental jam featuring some of his students.

Brimming with rocking grooves and heartfelt performances, Hamilton Loomis’ Basics is anything but.

—Melanie Young

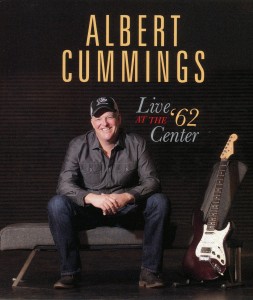

ALBERT CUMMINGS

Live at the ’62 Center

Ivy Music Company – No #

Albert Cummings returns home to play his powerful brand of blues rock to a joyous crowd. On October 15, 2016, Cummings, joined by Warren Grant on drums, Yanko Valdes on bass, Pete Levin on keyboards and Kit Holiday and Lydia Harrell on background vocals, played a raucous, rumbling, fiery set at the ’62 Center for Theatre & Dance at Williams College in Cummings’ hometown of Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Cummings prowls up and down the neck of his guitars, sometimes like a menacing lion searching for the killer chord and sometimes like a domestic cat looking to trap an unsuspecting note and play with it until it bends to his will. No Doubt opens with a scalding lead that deftly moves into a phrase from Hendrix’s Crosstown Traffic that serves as the underlying musical theme of the tune. Cummings growls his way around power chords and just-right lead riffs to question his lover’s faithfulness and the consequences of her cheating. Cummings sometimes forces too many notes into his lead solo on the bridge, which means he misses some notes here and there, but he’s a crafty player who dazzles with his ability to run the neck with speed. Holiday and Harrell’s ethereal background vocals are a highlight of the song. A musical phrase from Elvis’ Little Sister (penned by Doc Pomus) kicks off the down-in-the-heart I’ve Got Feelings Too, a blues stomp in which Cummings soars on his lead solos. Lonely Bed is a slow-burning jazz blues number introduced by Cummings’ string-bending lead runs; the influence of the late, great Alvin Lee of Ten Years After is clear on the phrasing of Cummings’ solos on this song. Cummings and his band deliver a choogling, soulful take on Elmore James’ Hurts Me Too; Levin takes a turn on a keyboard solo that might be the highlight of this version, for otherwise this version is not especially memorable. The album closes with a medley of Cummings’ Glass House and Dickey Betts’ Midnight Rider; the best part of Midnight Rider is the background vocals, but Cummings manages to capture the lonely desperation of the song with his power chords, especially in his lead solos on the bridge. It’s a fitting way to close the evening and the album.

Live at the ’62 Center illustrates that hearing it live is the way to listen to blues rock. This is evident in the DVD of the performance that is also available now, but even if you didn’t have the DVD to watch, you can feel the energy of the crowd on this album, urging Cummings to higher and higher ground in his solos and his singing. Cummings’ music clearly lifts the crowd—and us—out of our seats.

—Henry L. Carrigan Jr.

THE SWAMPERS

Muscle Shoals Has Got the Swampers

Malaco – MCSD8026

Long before Lynyrd Skynyrd made them famous with the lines “Muscle Shoals has got the Swampers / and they’ve been known to pick a song or two,” this group of studio musician—the Swampers—was making some of the most memorable music of the late ’60s and early ’70s. Keyboard player Barry Beckett, bassist David Hood, guitarist Jimmy Johnson and drummer Roger Hawkins met up at Rick Hall’s FAME Studio in Muscle Shoals in 1967, where they played on James and Bobby Purify’s I’m Your Puppet. The group soon created their own studio called Muscle Shoals Sound, located at 3614 Jackson Highway. In this studio the Swampers laid down tight rhythm tracks for Aretha Franklin’s Respect, R.B. Greaves’ Take a Letter Maria, the Stones’ Brown Sugar and Wild Horses and Paul Simon’s Kodachrome, among hundreds of other well-known tunes.

Now we get to hear the Swampers in all their glory on Muscle Shoals Has Got the Swampers, a collection of previously lost tracks. While many of the tracks were recorded at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio between 1969 and 1978, some were recorded in the ’90s at the Swampers’ second studio at 1000 Alabama Avenue. As David Hood says, “we’re so pleased; we had so much music, and we never thought it would see the light of day.”

The 14 instrumentals on the album showcase the incredibly tight playing of the band, as well as canny songwriting. Above all, though, these songs capture the moments when four of the world’s best musicians gather around and play just for their own pleasure. The genius of the Swampers is their sure-handed ability to play every style of music. On Don’t Bug Me Johnson, Barry Beckett (who wrote the tune) rambles sparklingly over his keys, and Jimmy Johnson replies with his lead riffs on the song’s bridges in a call-and-response fashion. It’s a crafty jazz suite that recalls Brian Auger’s Oblivion Express. Muscle Shoals, written by the band, starts out with a Santana-like drum solo before moving to a lush, slow and sensuous jazz overture that pays homage to the beauty of their home, the Shoals. Whiplash, written by guitarist Pete Carr, features his crisp, clean, shimmering guitar riffs laid down over a swampy jazz foundation; the riffs recall the lead guitar of Three Time Loser on Rod Stewart’s Atlantic Crossing (1975), on which Carr and the other Swampers played. Backporch Soul is a laid-back, slow groove—that has some moments resembling Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers—while Cruisin’ Jackson Highway jumps propulsively down the road, capturing the feel of driving around the Shoals. Eddy’s Place is a jump blues number that would propel listeners out of their seats at any juke joint in town.

Muscle Shoals Has Got the Swampers gives these incredible musicians their due, allowing them to shine brightly and giving us a chance to hear their own tightly crafted styles. We can only wish there’s more of their music still to be released.

—Henry L. Carrigan Jr.