Investigating the Death of Bessie Smith

Investigating the Death of Bessie Smith

by Jim O’Neal

This document contains the full text of Dr. Hugh Smith’s reply to reporter B.J. Skelton as well as some of Skelton’s own observations and an account from Smith’s drummer Dave Oxley.

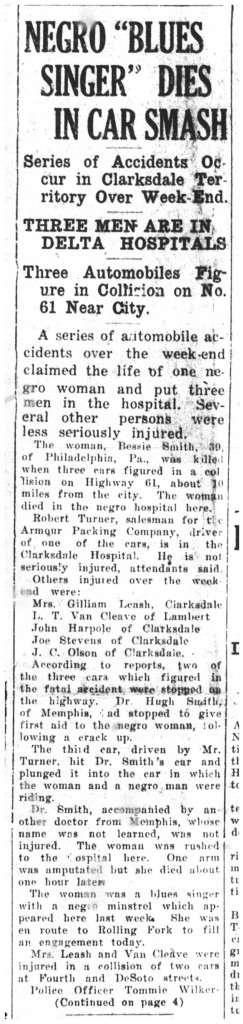

The first report on Bessie Smith’s death made front page news in the Clarksdale Register & Daily News on the day of her death, September 26, 1937, headlined NEGRO “BLUES SINGER” DIES IN CAR SMASH. In 1957, on the 20th anniversary of the tragedy, and amidst false accounts that continued to circulate, Press Register staff writer B.J. Skelton took it upon himself to set the record straight by corresponding with Dr. Hugh Smith in Memphis and talking to the black ambulance driver and the white tow truck operator who responded to the fatal crash. The relevant portion of the 1937 article (which dealt with several accidents), Dr. Smith’s letter in reply to Skelton, and some of Skelton’s own observations are printed here. Bessie biographer Chris Albertson only reached Dr. Smith 14 years after Smith’s version of events had been published in the Skelton article–but few researchers outside of Clarksdale knew that Skelton’s manuscript and Smith’s letter were in a file at the Carnegie Public Library.

Clarksdale Register & Daily News, Monday, September 26, 1937,

NEGRO “BLUES SINGER” DIES IN CAR SMASH

Three Automobiles Figure in Collision on No. 61 Near City

A series of automobile accidents over the week-end claimed the life of one negro woman and put three men in the hospital. Several other persons were less seriously injured.

The woman, Bessie Smith, 39, of Philadelphia, Pa., was killed when three cars figured in a collision on Highway 61, about 10 miles from the city. The woman died in the negro hospital here.

Robert Turner, salesman for the Armour Packing Company, driver of one of the cars, is in the Clarksdale Hospital. He is not seriously injured, attendants said.

According to reports, two of the three cars which figured in the fatal accident were stopped on the highway. Dr. Hugh Smith, of Memphis, had stopped to give first aid to the negro woman, following a crack-up.

The third car, driven by Mr. Turner, hit Dr. Smith’s car and plunged it into the car in which the woman and a negro man were riding.

Dr. Smith, accompanied by another doctor from Memphis, whose name was not learned, was not injured. The woman was rushed to the hospital here. One arm was amputated but she died about one hour later.

The woman was a blues singer with a negro minstrel which appeared here last week. She was en route to Rolling Fork to fill an engagement today.

Jim Albino of the Owl Service Station said his wrecker was called out to bring in eight cars. Other garages and motor companies had several wrecked cars.

LETTER FROM DR. HUGH SMITH, Campbell Clinic, Memphis, Tennessee, August 27, 1957

[This letter appeared in edited form in the Clarksdale Press Register of October 3, 1957, as part of B.J. Skelton’s article. It is transcribed in its entirety below, as best we could make out from a Xerox of an old carbon copy at the library.]

Dear Mr. Skelton:

It was indeed some twenty years ago when Bessie Smith was fatally injured in an automobile accident. At approximately 2 a.m. on a Sunday morning (this was Sept. 26, 1937), some 14 to 16 miles north of Clarksdale, an associate of mine, Dr. Broughton (now deceased), who was the brace-maker for Campbell Clinic, and I were on our way to a farm some 14 or 16 miles on the other side of Clarksdale to do some fishing. It was a clear night with no fog. I had a new Chevrolet with about 500 miles on it and the back seat was loaded down with fishing equipment. We came upon an automobile, obviously a total wreck. It was, for those days, a quite old Packard—one of the kind with a wooden frame for the top; it was a four-door Packard. It was lying on the side across the right lane with the front of the automobile pointed due east. A tall Negro man, probably in his late 20s or early 30s, waved us down. We came to a stop some 30 feet from the automobile with my lights shining on a colored woman lying on the concrete road, obviously in serious condition. The colored man gave me the following story:

A trailer truck—a large one, capable of hauling some 16 or 18 thousand pounds of load, had apparently pulled off of the highway to check his tires and had started to pull back onto the highway and had just cleared the road when he, the colored man, and Bessie Smith drove practically underneath the tail gate of this large truck. It sheared the wooden top off the Packard, turned it over and apparently threw its occupants out into the road. The truck driver had informed the injured people that he was carrying U.S. Mail and was also carrying the Sunday morning Commercial Appeal and had a time schedule and had to go on but he told the colored man that he would go on into Clarksdale and send an ambulance back to pick them up. He had departed the scene of the accident for two or three minutes when we arrived. It was a clear night with no fog. The stars were out and there was no moon.

My associate and I jumped out of the car, and I examined the colored woman in the light of my headlights. Her left arm, at the elbow, had been torn completely loose at the joint; viz., in essence, a traumatic amputation except that the main artery was still intact. She was bleeding profusely. A tourniquet was applied, and Mr. Broughton was sent to a nearby farmhouse to call in to Clarksdale and be certain that an ambulance came promptly. Obviously, this woman had severe internal injuries to her chest or abdomen, but she was conscious. Bessie Smith was placed beside the road. When some 12 or 14 minutes had elapsed and no ambulance had put in an appearance, Mr. Broughton and I began to clear the fishing equipment out of my car with the idea of putting her in there and taking her on into Clarksdale. While we clearing out the fishing equipment, an automobile coming at a relatively high rate of speed could be heard in the distance. I began to flash my lighs [sic] on and off and endeavored to warn him of impending danger. He never saw my automobile. He ran squarely into the rear just as Mr. Broughton and I jumped from my automobile. We narrowly missed getting killed. The impact of the automobile drove mine into the Packard, which was lying across the road, and buckled it into the middle and literally tore it up. I received $100 for the junk. Since this was my first new automobile (and it wasn’t paid for by the way) you can imagine that I was not a very happy man at the penalties I had just paid for being a good Samaritan. Then Mr. Broughton and I proceeded to get a white man and a lady out of the automobile which had hit mine. She was hysterical but did not appear to have been injured badly. The gentleman driving the car (it was a Swift Packing Company automobile) was in extreme pain. It appeared as if he had many fractures of his ribs from being struck at the steering wheel but he too did not appear to be in critical–just extremely painful, condition. Now, we had three patients on our hands, all lying on the grass, beside three wrecked automobiles. At approximately this time, traffic began to pile up a bit but simultaneous with this, the ambulances began to appear and all three injured people were promptly dispatched to Clarksdale in two different ambulances. I waited until a state trooper appeared to give him full details of the accident. I would suspect that the archives of the Mississippi State Police would verify all of the details given up to now.

Later in the morning, I proceeded to my host’s farm and tried to do a little fishing, but my heart was not in it. I was brought back to Clarksdale and caught an afternoon train for Memphis. Before I left Clarksdale, I, by chance, ran into the ambulance driver and inquired as to Bessie Smith’s condition. He advised me that she had been taken either to a Negro clinic or a Negro hospital and expired several hours after arriving.

You will be interested in this side light to the death of Bessie Smith. sidelight added by Dr. Smith. I was in New York as a technical adviser for an Army training film on a medical subject and spent some four or five days at the Army Signal Center, out in Brooklyn. This was in 1949 or 1950. One evening, an Army officer and I went downtown in New York, somewhere in Manhattan, for a steak dinner. We just by chance wandered into a steak house and had not completed our meal when a party began in the back of the restaurant for a young entertainer who was being inducted into the Army in the near future. A sizable number, some 15 or 20 entertainers, at one time or another wandered into that restaurant in the next ___ hours. We sat and listened for the music and entertainment that was ___ good. It was a spontaneous sort of demonstration. I remember that Fletcher Henderson played the piano at length for three or different singers, that there were two or three comedians there and a ___ mixture of theatrical people present. By chance the name of Bessie Smith was brought up. I listened to the rather colorful reports of the details of her accident and supposedly neglect; one account had her in the ditch with the white people “passing on the other side.” I believe that even “Downbeat” probably published the inaccurate account, though I am not positive of this fact; anyway, at least 15 jazz musicians and entertainers were given accurate details. Before I left New York, I called Bessie Smith’s former manager to inform him of the details; he was not interested. Their association had been broken for quite some years, and he had no particular interest in the matter whatsoever for by this time Bessie Smith had apparently declined from stardom, was nearly broken and was singing in tent shows throughout Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia.

I should think that you would be able to scare up details of all incidents from the time she left the wreck through to her death by inquiring among various doctors in Clarksdale and also from former ambulance drivers in Clarksdale.

If I can supply you with any additional information, please call upon me.

Sincerely yours,

Hugh Smith, M.D.

The following excerpts are from the B.J. Skelton article:

It has been 20 years since Bessie Smith was killed in an automobile crash near Clarksdale–nearly 40 years since she reached the peak of her fame singing “Hard Drivin’ Papa” and “Reckless Blues,” but her memory and melodies linger on, as immortal as the blues themselves.

Bessie died on Sept. 26, 1937, under mysterious circumstances which perhaps are only now becoming uncovered.

Her death came a few hours after an automobile accident (on Highway 61 several miles north of Clarksdale) either on the way to a Negro clinic which was in operation at that time on Sunflower St. or at the clinic.

According to newspaper accounts of her fatal accident, the once highest paid Negro entertainer in the country had sung in Clarksdale the preceding week with a traveling minstrel show and on the night of the wreck was on her way to Rolling Fork for a similar engagement.

Bessie was one of five Smiths–the others were Mamie, Laura, Trixie and Clara–who recorded in the early 20s but who were not related, even in style. Bessie, who was married to Jack Gee, a Philadelphia policemen (her address was given as Philadelphia at the time of her death) at one time was a headliner in Milton Starr’s top-ranking Negro vaudeville circuit, and her records were to outsell those of any other Columbia artist before her time.

Her Clarksdale wreck came on the eve of another quest to bring her back to New York to record again.

As rich in pathos and drama as Bessie Smith’s life was, the myth makers of the jazz world apparently felt obligated to add a postscript. A fatal automobile accident was violent, to be sure, but more purple was needed for the sunset; double indemnity was not enough.

So the story, probably unchallenged in print until now, was told–and retold until it became established “the most solidly documented version of her death–that Bessie’s last cruel blow from fate was an unnecessary death that she died because she was denied admission to a white hospital, and died on the way to one which accepted Negroes.

At that time there was a small Negro hospital at 615 Sunflower. It had been opened just before World War I by Dr. T. G. Hughes, Dr. I. P. Carr and the late Dr. John Primrose. Later the hospital was operated by the late Dr. S. D. Robinson and by the late G. T. Thomas. It is indefinite as to who had the hospital in 1937–probably Thomas, a Negro property owner who died last year–but white doctors continued to work there.

(The hospital ceased operations about 1940 and since 1944 the building has been operated as a Negro hotel and rooming house, and is now called the Riverside Hotel and Cafe.)

The state patrol records were not checked since their information would be mainly what Dr. Smith told them, but the ambulance driver was located and asked about his recollection of the accident.

His name is Willie George Miller, now with the J. O. Patterson Funeral Home in Memphis. At the time he was with the L. P. Gibson Funeral Home in Clarksdale, which later sold out to Century Burial Association.

Miller, although confessing that his memory is a little hazy, says that he believes Bessie “passed” while on the way to the Negro hospital here. He said definitely that the woman was not taken to a white hospital, and wasn’t transferred to any other hospital outside of Clarksdale.

Another man on the scene was Jim Albino of near Clarksdale, who operated the Owl Wrecker Service for many years. Mr. Albino didn’t know what happened to Bessie Smith, since a Negro ambulance had picked her up, but he does remember what happened to the Packard in which she was riding. He took it on the wrecker bill.

Mr. Albino converted the ancient machine into a wrecker and used it for two or three more years before finally junking it. Bessie’s Negro male companion has never been identified.

He recalls that the Negro man with Bessie Smith told him that he didn’t want the car and that Mr. Albino could keep it for his services.

The newspaper account matches that of Dr. Smith except for details—Dr. Smith had Turner with Swift, the reporter with Armour; the doctor placed the wreck 14 miles north of the city, the newspaper 10.

Attempts to further document the circumstances of that particular weekend–which incidentally, was climaxed with a low reading of 47 degrees early the Monday morning after–have been unavailing. The operator of the funeral home whose ambulance carried Bessie to the hospital moved away several years ago and subsequently died, and since the Negro hospital on Sunflower ceased operation not long afterward, no records are available from that source.

The only two physicians here who could have possibly treated Bessie, Drs. Carr and Hughes, do not remember it.

There has been no evidence furnished that Bessie or any other Negro ever was denied treatment at the old Clarksdale Hospital for whites, now a chronic disease center, or that any ever were brought there. While Negroes, on the whole, didn’t have medical facilities equal to whites in those days, there is nothing to support the story that any lack of medical attention caused her death. Certainly, she didn’t get the care she would have now at the Coahoma County Hospital, which serves both races, but neither was this level of treatment available to whites in the 1930s.

The circumstances of Bessie Smith’s death, whatever they are, cannot add to or otherwise affect her colorful career, just as fact, no matter how firm, cannot stand up against emotions.

The brief meteoric career of this “gosh – darn county woman,” this “real southern singer,” who at one time commanded $1,500 per week for her interpretation of the heritage of her people, requires no fictional retouching. The saddest thing of all was the sorry struggle of the last years of a woman who vowed “I Ain’t Gonna’ Play No Second Fiddle.”

But as her records, still popular, continue to be played on through the years, many, many listeners will say with an old admirer that they too have “never heard anything like the torture and torment she put into the music of her people.”

DAVE OXLEY TELLS HIS STORY

“Dave Oxley Tells His Story,” an account with some different details of Bessie’s death as recalled by Oxley, a New Orleans drummer, appeared in the September-October 1970 issue of The Second Line in Gorge W. Kay’s column “Good Sounds in the Distance”:

“In 1937, I joined the ‘Broadway Rastus Show’ which was owned by E.H. Winstead of Fayetteville, N.C. He asked me to join the show in Newport, Tennessee. I was with the show for about three weeks when Bessie Smith came on the show. They needed someone to do the concerts after the main show so Bessie was hired. I imagine we were together for about three months before the accident.

“We were playing a little town called Darling, Mississippi, on Saturday night. We were going from there to Hollandale. Most of the people in the show wanted to leave early in order to get the best rooms in the next town. That Sunday morning Bessie and her husband drove ahead in a big pink Chrysler. I was driving the bus carrying 35 passengers and we were following Bessie. Ten miles out of Clarksdale they sideswiped a cotton trailer. Bessie had her right arm hanging out the window and the impact tore her arm completely off . . . just a little piece of flesh hel d it . . . She practically bled to death. When I ran up to the scene of the accident, Bessie was sprawled out on the highway and we wanted to move her. We called for an ambulance at Clarksdale but it was hard to get one. So I had to call for an ambulance in Memphis, Tennessee. Two undertakers I knew of in Memphis were Hayes and Langston and Emma Welborn. So we got in touch with Hayes and Langston but that was about 90 miles away.

“While we were waiting for the ambulance, a white doctor from Memphis drove up and got out of his car to see what he could do for her. He tried to do all he could and when he found out she was Bessie Smith, he tried to do even more. The thing that really got me was the story so many people told that the doctor and his wife were there . . . that when she saw Bessie in all that blood, she fainted. So instead of taking Bessie to the hospital, the doctor took his wife. Well, all that was a big lie. There was no doctor’s wife because he was alone. I can’t think of his name but Esquire Magazine took my story and they contacted the doctor and got his name and all the facts. Bessie simply died from loss of blood.

“That night we had to take down all the posters advertising Bessie in the surrounding towns. We had about two weeks out anyway, so the old man just decided to close the show. We stayed over that Sunday night in Cleveland, Mississippi. Then the show was supposed to be go back to Fayetteville, but I didn’t go along. I came with my wife back to New Orleans. That is exactly what happened in the death of Bessie Smith.”

************