TRUDY LYNN

I’ll Sing the Blues for You

Connor Ray Music – No #

Trudy Lynn has a good thing going with Connor Ray Records. This late 2016 release, the Houston singer’s third for the label in the last three years, completes a trifecta of fine productions. Collaborating with producer Rock Romano on each album, Lynn has selected gems from the discography of classic blues (especially, but not exclusively, those written by women), which she reinterprets in new arrangements. Also—though less so on this new disc than previously—she augments each set with some of her own songs, which consistently mesh well with the vintage material. That strategy delivers again on I’ll Sing the Blues for You, as does the superb backing by a quintet of ace instrumentalists. A first-rate interpreter, Lynn infuses each track with strong vocals and her down-to-earth charisma.

The opener, a Big Mama Thornton number, kicks off with a lone harmonica call, a soulfully squalling summons that soon engages the band in a rollicking shuffle. Honking that lead solo on harp, Steve Krase splendidly sets up Lynn’s fiery launch into the first verse. It’s a musical moment befitting Krase’s key role in Lynn’s recent comeback, on record and on stage—which she gratefully acknowledges in her self-penned liner notes. Indeed, despite some excellent solos by both the keyboardist Randy Wall and the guitarist David Carter, it’s Krase’s harmonica that emerges as an understated but significant second “voice” across this whole record, often engaging in back-and-forth interplay with Lynn’s vocalizations or melodically accenting the ends of lines. As a whole, the instrumentation is never obtrusive, sometimes almost sparse, effectively spotlighting the songs and the singer.

Of course, Lynn’s own compelling voice ultimately defines the ten-song set. Especially notable tracks include her own Thru Chasin’ You, a break-up song which rides a liberated and funky groove, concluding with a satisfyingly defiant laugh; the Memphis Minnie tour de force World of Trouble, in which Lynn growls, moans, and shouts with palpable hurt and despair; and the calypso-driven New Orleans R&B jewel Still My Angel Child by Alma Mondy. But for this listener, the nonpareil is the closer, Down on Bended Knee, written and originally recorded in 1963 by Johnny Copeland, Lynn’s late friend and longtime fellow Houstonian. It’s the kind of raw blues—with its desperately pleading lyrics and primal but compelling musical structure—that Lynn can croon with raspy, robust conviction, as few others can.

As the title of this album asserts, Trudy Lynn is committed to singing the blues. With its smart set list, sterling musical support and her own well-honed interpretive skills, she once again convincingly makes her case.

—Roger Wood

RONNIE BAKER BROOKS

Times Have Changed

Provogue – PRO 7509-2

The title of this CD, reflecting its overall theme, is celebratory but also elegiac. Ronnie Baker Brooks, son of Lonnie Brooks, is both a dedicated roots man and a forward thinker unafraid to incorporate modernist influences—including, on the title tune, rapper Al Kapone. “Ain’t nothing wrong with going back to the basics,” Kapone raps, adding that “some thangs change for the better, too.” In that spirit, the songs here are split between standards and originals, and although instrumentation is straight-ahead throughout, there are nods to genres ranging from postwar blues and pre-deep-soul R&B through post-funk and beyond.

Appropriately, that funk is often toughened by irony (as in the hard-times lament Long Story Short) but it’s always exuberantly danceable; Brooks’ old-school leanings are further evinced by his updatings of chestnuts like Joe Tex’s Show Me (featuring fatback lead guitar from Steve Cropper) and the Chicago soul dance classic Twine Time. Even more notable (and poignant) are guest appearances by now-departed legends like Bobby “Blue” Bland (fragile but unbowed on the Robert Cray ballad Old Love—

quite possibly the last recording Bland ever made) and, on several tracks, Hi Rhythm Section guitarist Teenie Hodges. Ex-Rascals frontman Felix Cavaliere sounds as indefatigable as ever on the hard-charging Come on Up (featuring Lee Roy Parnell on rhythm guitar). Other notable guests included a sultry (and multi-tracked) Angie Stone (on Curtis Mayfield’s Give Me Your Love [Love Song]) and “Big Head” Todd Mohr (on Joe Tex’s Give the Baby Anything the Baby Wants and Brooks’s Doing Too Much).

Brooks wrote or co-wrote five of the songs here, and he’s as eloquent a wordsmith as he is a musician. His guitar work is both fiery and richly seasoned. He has the knack of spiking subtlety with hard-driving passion—

even his most ecstatic flights of fancy sound well-thought-out and impeccably musical. There isn’t room to list all the sidemen, but suffice it to say that Teenie Hodges was only one of many Memphis soul legends who participated in this project (significant portions were recorded at Willie Mitchell’s Royal Studio, which should tell you all you need to know). It’s not easy to keep one’s feet firmly grounded while allowing one’s mind and inspiration to fly free—but that’s exactly what Ronnie Baker Brooks has done here, and the results are outstanding.

—David Whiteis

THE ROLLING STONES

Blue & Lonesome

Polydor/Interscope – B0025916-02

The sessions that resulted in the Rolling Stone’s Blue & Lonesome, which took place over three days, were not so much aimed at making a new studio album as they were at capturing a band performing the blues in progress and in motion. When Mick Jagger states that the band could not have done the album in the early 1960s because they had not lived enough, he goes on to assert: “Equally if we had made this a week later than we did, it would have been different again.” What he seems to be pointing out is that these 12 recordings of classic blues songs capture spontaneous live performances of a band drawing on over five decades of listening to and playing this music that gave them their raison d’être all those years ago.

That the Rolling Stones would some day devote a record to their blues roots is something that has tantalized listeners who have been drawn to both the blues and the band for years. Initially, what is most striking about the project finally coming to fruition is the focus on the idiom and the choice of material, especially because of the spotlight it shines on the original masters. However, what becomes clear upon listening—and serious listening is required—is that Blue & Lonesome, first and foremost, is all about a band playing together, interacting on a visceral level to make these songs work as they were intended to work. Check out their interpretations of Eddie Taylor’s Ride ’Em on Down or Howlin’ Wolf’s Just Like I Treat You (written by Willie Dixon). On the original recordings from the 1950s and 1960s, the parts that the individual band members were playing were like the gears in a machine dedicated to driving folks to the dance floor, to make listeners tap their feet, nod their heads and clap their hands. The agenda is the same for the Stones in 2016.

Even the sprawling, famously excessive sessions that yielded their blues-rock masterpiece, Exile on Main Street, were ultimately focused on the production of an artifact, a final recording. That is not the case with Blue & Lonesome. It is all about what is happening between the band members in the room playing a particular song in that moment. And when a band clicks like the Stones do on these tracks, the results are magic. Eric Clapton bore witness to the blues magic he found upon walking into that studio: “Can you believe this? I used to go and see these guys play in Richmond and I’m right back there in the audience.” Clapton is transported back to his experiences with a live band working a crowd, and when he picks up the guitar for Little Johnny Taylor’s Everybody Knows About My Good Thing and Otis Rush’s I Can’t Quit You Baby (another Dixon tune), he does not deliver flashy guitar heroics; he becomes part of the band, listening and interacting with the other musicians to craft effective performances.

Blue & Lonesome is certainly the type of project that Keith Richards has dreamed about for years, but on first listening it is Jagger’s contributions, both as a vocalist and even more strikingly as a harmonica player, that stand out. But then, the spotlights and the cameras have always been drawn to him, but the listener who digs deep into this music (and listening with headphones certainly is revelatory) will find that all four Stones are equal partners in bringing these blues to life. The guitar “weaving,” as Richards likes to call it, is simply stunning. Wood and Richards are telepathic in their blues-riffing dialogues, creating devastating sonic textures to underpin Jagger’s singing and harp. Watts remains the master of stunningly effective simplicity and understatement and possesses the ineffable ability to generate just the right feeling and swinging energy for each performance. Richards has said that he wants the line, “He passed it on,” written on his gravestone. Over the decades, the Stones have played a vital role in passing on knowledge of the blues and the artists who pioneered the tradition, and with Blue & Lonesome, they also have passed on what it means to really play in a band.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

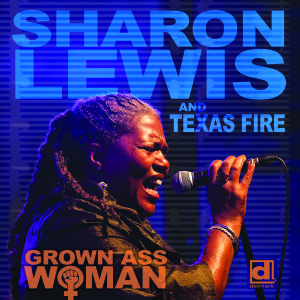

SHARON LEWIS AND TEXAS FIRE

Grown Ass Woman

Delmark DE 849

Sharon Lewis, a Chicagoan by way of Texas, Oklahoma and California, released her well-received Delmark debut, The Real Deal, in 2011 and now is back with this impressive sophomore effort.

Like its predecessor, this set finds Lewis supported by her working band, augmented at times by a three-piece horn section arranged by trumpeter Kenny Anderson and a well-chosen guest list—this time, it includes harp men Sugar Blue and Steve Bell, bassist Ari Seder and guitarist Joanna Connor. The ever-reliable keyboard wizard Roosevelt Purifoy returns, as does drummer Tony Dale, with Andre Howard replacing Melvin Smith on bass and Steve Bramer taking over the guitar chores from Bruce James. This last substitution proves crucial, as Bramer penned half of the set’s dozen original songs and brings a measure of rock sensibility that takes the proceedings to a higher energy level. The title song is but one of several tracks where Lewis proclaims her independence in no uncertain terms, while she proudly stakes her claim to the blues birthright on the opening Can’t Do It Like We Do before rocking the dance floor on Hell Yeah! She summons a more traditional sound on Home Free Blues, evokes Little Walter’s It Ain’t Right and Bobby Bland’s That’s the Way Love Is on Old Man’s Baby and Call Home, respectively, ventures near jazz on Walk With Me and pop on Freedom and slows the tempo to call out the rumor mongers on the country-tinged They’re Lyin’. The program’s last two slots are reserved for its covers, B.B. King’s Why I Sing the Blues and Warren Haynes’ Soul Shine.

Grown Ass Woman marks a significant step forward in Lewis’ career and should solidify her standing in the front ranks of the current bumper crop of women singing the blues.

—Jim DeKoster

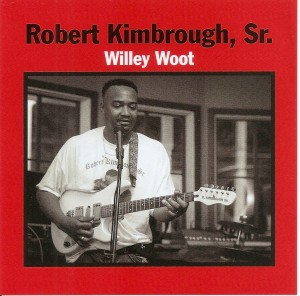

ROBERT KIMBROUGH SR.

Willey Woot

No label – No #

Robert Kimbrough Sr.’s music invokes that of his father, the late Junior Kimbrough. It’s primal, hard-grinding, devoid of pretense or nuance and often delivered in the single-chord “trance blues” style associated these days with the Mississippi Hill Country.

Credits are a little unclear: Kimbrough is pictured playing guitar on the CD’s front cover, but he can also play bass; his band here includes two other versatile fretmen—brother David Kimbrough Jr. and family friend Duwayne Burnside (son of the late R.L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough’s longtime friend and colleague)—along with another brother, Kenny Kimbrough, on drums. Presumably either David or Burnside handles most of the lead guitar chores—solos are fiercely energized in the post-Hendrix fretboard-burning manner. Several of the songs are cast in a stripped-down southern soul style, more evidence that the Kimbroughs and the Burnsides can incorporate modern influences without sacrificing any of their atavistic aggressiveness.

Kimbrough’s lyric themes are as uncompromising as his music—listeners with tender sensibilities should beware. Many of his storylines seethe with barely submerged violence, often directed toward women accused of doing wrong: “I got my hammer on my side,” he croons in the opening track, Girl Is Gone. “Get the sheet / and cover that girl up . . . Find a hole, hole in the wall / Put her in / Now the girl is gone . . .” Things get darker from there.

Occasionally, though, Kimbrough hints at a softer side. You Laugh at Me finds him addressing a universal theme of grief and guilt, as he laments never having the opportunity to fully make peace and mend bridges with his father (Junior Kimbrough died in 1998). The concluding View the Remains bemoans the loss of Junior’s legendary Chulahoma juke (it burned down in 2000), bringing things to an appropriately elegiac, if not exactly healing, conclusion.

It may be a cliché, but the blues don’t get any rawer, or more real, than this.

—David Whiteis

VALERIE JUNE

The Order of Time

Concord Records – No #

Valerie June’s 2013 album, Pushin’ Against a Stone, brought the multi-instrumentalist and singer-songwriter critical acclaim and a new level of visibility (LB #226). Since then, the Tennessee native has been touring and patiently working on new material. The result is The Order of Time, and this exquisite collection of songs is her best effort to date.

Produced by Matt Marinelli, the album’s dreamy, hazy soundscape unifies the blues, R&B, country and gospel elements in June’s music, and it’s an ideal setting for her willowy, honey-in-the-rock voice. She explores different facets of love and the nature of time on several tracks, including the beautifully aching Love You Once Made, If And and The Front Door. Great songwriters understand the power of economy, and the latter song in particular conveys a deep well of feeling and meaning with few words. Strings enhance the sweetness of Just in Time and With You, while keyboards and horns give Slip Slide On By and Got Soul shots of classic soul.

June makes the Hill Country–esque Shakedown a family affair with her father, Emerson Hockett, and brothers Jason and Patrick Hockett providing backing vocals; the banjo-driven Man Done Wrong has a similar, droning feel. Norah Jones, who recently toured with June, also sings backup on Love You Once Made, Shakedown and Got Soul, and their vocal pairing is an inspired match.

“The day will come / When you are ready / Just trust,” she sings on the gorgeous, existential Astral Plane. Valerie June has been content to do just that, and The Order of Time is proof that her instincts are true.

—Melanie Young

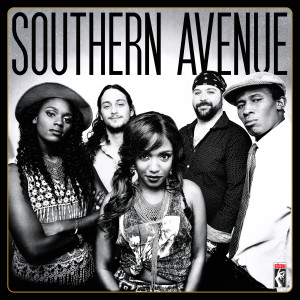

SOUTHERN AVENUE

Southern Avenue

STAX – STX – 00159

Southern Avenue is already garnering serious media buzz, at least partly because their debut CD is on the newly revitalized Stax label—meaning instant cred, but also, at least potentially, a crushing weight of history on their shoulders. The good news is that they sound as if they have the chops and musical vision to both live up to the hype and honor the history without getting suffocated by it.

Lead vocalist Tierinii Jackson and her sister, drummer Tikyra, came up in the church; Israeli-born guitarist Ori Naftaly came to the U.S. in 2013, competed in the International Blues Challenge and has lived and worked here since. Bassist Daniel McKee brings a jazz influence to the mix, and keyboardist Jeremy Powell is an alum of the Stax Music Academy. Their sound reflects their diversity. At various points along the way, we hear healthy doses of Memphis deep soul, pop/rock-charged blues, roots gospel, jazz-tinged neo-soul, flat-out rock ’n’ roll and even a few dashes of country-fried honky-tonk boogie. (All of the songs, except for an updated version of the Ann Peebles hit Slipped Tripped and Fell in Love, are originals; lyric themes range from the usual dispatches from the front lines of romantic and erotic infatuation to calls for social justice and healing—another nod, of course, to the band’s Memphis soul roots.)

The musicianship throughout is solid, and often considerably more than that. Both drummer Tikyra Jackson and guitarist Naftaly rise to the challenges posed by the band’s varied stylistic swerves with disarming facility, providing a perfect springboard for Tierinii Jackson’s vocals which are—in a word—thrilling, especially coming from one so young. In command of a multi-octave range, declamatory but never shrill, she negotiates complex melodic and emotional mazes with seeming effortlessness, snarling like a wildcat one minute, crooning like a fallen-angel siren the next, and then toughening into a muscular growl as she testifies her determination to keep faith (personal, political and spiritual) in the face of challenges and despair. This lady embraces, empowers and sanctifies everything she touches.

—David Whiteis

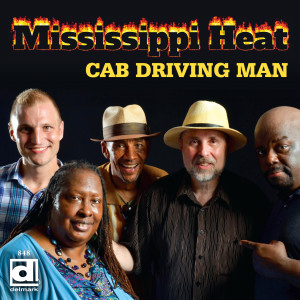

MISSISSIPPI HEAT

Cab Driving Man

Delmark Records – DE-848

Harmonica player Pierre Lacocque obviously works hard with his Chicago-based band, Mississippi Heat, to generate new material, writing and arranging most of the songs for each of his numerous releases, 12 thus far in their 27-year history. Cab Driving Man, their sixth CD for Delmark, does not shortchange the listener—the disc is packed with 16 tracks totaling some 67 minutes of music. Guitarist Michael Dotson, who has contributed songs to previous releases, adds three on this one.

It’s easy to understand Mississippi Heat’s popularity at clubs and festivals for the variety and complexities of their arrangements, all with an ear to danceability. With so much original material, it must be a challenge to keep the set list straight.

Singer Inetta Visor has become the primary voice of Mississippi Heat since joining in 2001. Though rock was the music with which she grew up and first sang, Visor has successfully channeled earlier generations, delivering each track with fevered, bluesy vocals. She finds succulent meat on even the leanest of songs.

To some ears, a few arrangements may seem unnecessarily busy and ambitious. Most appealing to this listener are the simpler productions like the gently loping Life Is Too Short, the sweet and bedrock traditional–sounding Mama Kaila and the lovely rumba, Lonely Eyes, which has the terrific line, “His eyes are golden brown / yet they look so blue.” Also very good are Dotson originals The Last Go Round, a Hooker-style boogie, and That Late Night Stuff, a fine boogaloo.

To spice things up, guests on this disc include guitarists Dave Specter (on the minor key Luck of the Draw) and Giles Corey (on three tracks), drummer Kenny Smith (on three), pianist Sumito Ariyo (on two), Sax Gordon (on five) and percussionist Ruben Alvarez, who adds Latin flavor to four of the numbers.

Pierre Lacocque and Mississippi Heat have been on the scene for a long while, playing locally and around the world, and are clearly poised to stick around.

—Justin O’Brien

RHIANNON GIDDENS

Factory Girl

Nonesuch Records – No #

Factory Girl is further testimony to the tremendous talent Rhiannon Giddens possesses and the impact she has made on the roots music scene thanks to her work with the Carolina Chocolate Drops, in addition to solo efforts that include her debut CD and contributions to such recordings as Another Day, Another Time, Lost on the River: The New Basement Tapes and Allen Toussaint’s American Tunes.

Each of the five tracks on the EP would have held its own on Tomorrow Is My Turn (they were originally recorded during the sessions for that 2015 breakthrough album) and highlights Giddens’ versatility as a singer. Both Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s That Lonesome Road and Ethel Waters’ Underneath the Harlem Moon illustrate her ability to generate an ebullient, bluesy sense of swing. Moonshiner’s Daughter, the lone original, is a heartfelt Appalachian-style ballad based on stories she heard about her great-grandfather’s bootlegging exploits. Giddens explores and expands the Irish folk tradition with two selections. On Mouth Music, she melds a traditional Celtic a cappella form with jazz scat singing and Adam Matta’s beatbox. The haunting ballad Factory Girl is expanded with new verses that memorialize the tragedy of a 2013 factory building collapse in Bangladesh.

Though puzzling, since there have been numerous deserving (actual) folk albums released during the qualifying timeframe, Factory Girl has been nominated for a 2017 Grammy for “Best Folk Album,” as well as for “Best American Roots Performance” for its title track. One aspect of these T-Bone Burnett–produced sessions that is somewhat disappointing is that Giddens does not employ her formidable skills on banjo or fiddle on any of the tracks. Yet, ultimately, it is that golden voice that has enchanted so many listeners, and that is certainly the case again with the five tracks that make up Factory Girl.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

OTIS RUSH

Double Trouble: Live Cambridge 1973

RockBeat – ROC-CD-3220

It’s comes as quite a jolt to realize that it’s been a full 60 years since a 21-year-old Otis Rush went into the studio to record his classic I Can’t Quit You Baby, the first of a string of recordings for Eli Toscano’s meteoric Cobra label that would be instrumental in reshaping the sound of the Chicago blues. That song made it to No. 6 on the Billboard R&B charts, but, for one reason or another, Rush was never able to maintain commercial success, and a 2004 stroke has prevented him from realizing the sort of late-life success enjoyed by his contemporary, Buddy Guy.

With a relatively scant discography of studio recordings, a fair number of Rush’s live performances have been released over the years, most recently this set recorded on May 4, 1973, at Joe’s Place in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the company of long-time bassist Ernest Gatewood, saxman Little Bo and ex-Magic Sam drummer Bob Richey, misidentified on the sleeve as “Bob Richards” (there also seems to be a piano deep in the mix, though none is credited). After introducing the band, Rush warms things up with his take on the Herbie Hancock / Mongo Santamaria jazz classic Watermelon Man before launching into It Takes Time, the first of four reprises of his Cobra classics that form the core of the program (the others are I Can’t Quit You Baby, Keep on Loving Me Baby and the iconic title track). We also get Gambler’s Blues, Please Love Me and Why I Sing the Blues from the B.B. King songbook and an instrumental version of Ike and Tina Turner’s 1961 Sue hit It’s Gonna Work Out Fine. Rush also gets to stretch out on the James Brown–inspired Popcorn and closes the set a la Brown with a surprising Please, Please, Please. Sound quality, while not exactly state of the art, is good enough to capture the impact of a Chicago blues band at full tilt.

With a recording date a couple years before his gigs in Japan and at Chicago’s Wise Fools Pub that are available on Delmark, this set stands as the earliest, and arguably the best, of Rush’s full-length live recordings. It finds him in fine fettle, both vocally and instrumentally, and is a stellar addition to the discography of one of the music’s masters.

—Jim DeKoster