ALBERT WHITE AND THE ROCKERS

ALBERT WHITE AND THE ROCKERS

A Sweat Soaked Night in 1970s Atlanta

Music Maker – MMCD181

Back in the 1960s, Atlanta guitarist Albert White worked in such elite local groups as his uncle Piano Red’s legendary Dr. Feelgood & the Interns and the Tams, but had been little heard from for many years when he and fellow Interns guitarist Curtis Smith showed up on a Music Maker CD by Beverly Watkins, the group’s “nurse,” in 1996. His own Music Maker CD, Soul of the Blues, followed in 2007, and he has continued to work with that organization as part of its traveling revue.

Now Music Maker has come out with this disc of a dozen vintage recordings featuring White in a variety of contexts. The bulk of the set—nine tracks—was recorded live at two different venues on the soul side of town in the late ʼ70s with the Rockers, a horn-driven outfit that served as the first-call band to back visiting soul acts. The selections include recent hits from Teddy Pendergrass, the O’Jays and Donny Hathaway as well as blues classics from Junior Parker, Charles Brown and Freddie King and a version of Funny How Time Slips Away that unexpectedly owes more to composer Willie Nelson’s original than to Joe Hinton’s 1964 hit. The set also includes a pair of home recordings with the Four Souls rehearsing the Tams’ 1968 hit Be Young, Be Foolish, Be Happy and the James Brown anthem There Was a Time, and it concludes with a brief Jesus in the Building from the ten-piece Gospel Crowns. Sound quality, from a portable cassette machine, is limited but tolerable.

While this is something of a departure for Music Maker, it’s a most welcome one, offering as it does an opportunity for time travel back to what appears in retrospect to have been a golden era.

—Jim DeKoster

GRADY CHAMPION

GRADY CHAMPION

One of a Kind

Malaco – MCD 7549

Grady Champion kicks off this set with Bump and Grind, a song originally recorded by Z.Z. Hill on Malaco in 1981; it’s now regarded as an early classic of the southern soul blues genre. Aside from being a not-so-subtle reminder of Malaco’s importance in helping to codify the modern blues sound, it also seems as if Champion (or his Malaco teammates) might be reaffirming his own link to both soul blues and the earlier 20th century blues lineage. Champion constricts his throat into a spit-and-gristle rasp evocative of Hill while his harmonica harks back to Sonny Boy Williamson II, whom he has cited as one of his original blues harp heroes.

That track, in fact, sets the tone for the entire set. Although many of Champion’s lyric and melodic conceits bespeak a modernist sensibility, he leavens it with a deep blues feel—shuffle rhythms, 12-bar song structures, an emphasis on passion-infused but unforced guitar work (from, at various points, Eddie Cotton, Mr. Sipp, Theodis Ealey and Elvin Bishop) as well as his own harp and, perhaps above all, those swamp-muck vocals. Even when the overall sound and/or subject matter comes closer to what one might expect from a southern soul modernist (Heels and Hips, One of a Kind), Champion sings like an unreconstructed back-country savant, weathered but unbowed, conveying life lessons and rakish witticisms with equal aplomb. Meanwhile, the instrumentation (the late Harrison Calloway arranged the horns—one of his very last recording projects) also conveys a rootsy feel, intentionally or not.

These days, quite a few artists are finding themselves struggling to create music that will appeal (and sell) to listeners on both sides of the putative “blues”/“southern soul” divide. Grady Champion’s new-school/old-school blend may not be the game-changing solution the world is looking for, but it seems to be working for him (he’s gigging steadily at venues ranging from casino show lounges to hipster blues clubs and roadhouses), and this recording should help him continue on that idealistic and hopeful path.

—David Whiteis

BIG BILL MORGANFIELD

BIG BILL MORGANFIELD

Bloodstains on the Wall

Black Shuck – BSR-003

The similarity between Bill Morganfield’s voice and his father’s is uncanny—all the more so since Bill has learned to relax and let that voice resonate on its own. Arguably, he’s expanded his scope—offerings range from the expected Chicago postwar chestnuts (associated with the likes of Otis Rush, Willie Dixon and Muddy himself) to gems from Lonesome Sundown (Lost Without Love), Jimmy McCracklin (Help the Bear) and Frank “Honeyboy” Patt (the nightmarish title tune). The overall ambience, though, is pretty much the same. In places, the old Chess studio sound is recreated with such verisimilitude that one is tempted to check the credits and see if Morganfield didn’t slip in an old backing track just to keep us awake.

Morganfield’s slide work also echoes Muddy’s, and so does much of his songwriting. When You Lose Someone You Love, for example, is modeled closely on You Can’t Lose What You Ain’t Never Had—although, in characteristic fashion, Morganfield makes it personal. Rather than a paean to lost romantic (or erotic) love, it’s a heartfelt meditation on his own grief over his mother’s death. (Help Someone, on the other hand, is a rollicking barnburner that sounds closer to New Orleans, or possibly Rosco Gordon–era Memphis, than the South Side of Chicago.)

The surprise here is the “bonus track,” a song Morganfield wrote and recorded for the upcoming Fox TV series Shots Fired. Updating Morganfield’s slide and rootsy vocals with electronically tweaked beats and hip-hop production, courtesy of noted studio maven C-Note, is sure to send chills down the spines of a lot of Morganfield’s long-time admirers (“Et tu, Bill?”), and I won’t pretend that many—probably most—LB readers won’t receive it with dismay; but, as Morganfield himself suggests, it may be just this kind of thing that the blues will need if it’s going to make the transition back into anything approaching the mainstream for the contemporary younger African American audience. If nothing else, a lot of young TV viewers who probably never thought they’d care about anything remotely associated with Muddy Waters will now hear his son providing some of the musical impetus to a show that depicts the hardscrabble reality of urban life as uncompromisingly as Muddy and his contemporaries did with their own “devil’s music” over half a century ago.

—David Whiteis

DAVELL CRAWFORD

DAVELL CRAWFORD

Piano in the Vaults, Vol. 1

Basin Street – BSR 1404-2

It is rather appropriate that New Orleans pianist/singer Davell Crawford has begun to release a series of solo piano recordings in light of the passing of Allen Toussaint in 2015. Piano in the Vaults, Vol. 1 represents a passing of the baton in the lineage of Crescent City piano professors. Crawford can take his position, along with longtime maestro Mac Rebennack, as the carrier of the flame for this tradition that reaches back to the turn of the 19th century Storyville. Crawford’s musical talent is so multifaceted that he is at home in jazz, blues, funk, gospel, R&B and rock, which often makes it hard to pin down a musical identity. But with these 13 tracks, recorded between 1998 and 2013, he makes it perfectly clear that this classic New Orleans piano sound and style are his source points.

With the first two tracks, Song for James and Booker Days, Crawford acknowledges the legendary pianist/singer James Booker as his central muse. The former is a jaunty catalog of Booker piano techniques, and the lyrics to the latter provide a personal reflection on Booker’s music. Crawford was a child prodigy on the piano, accompanying church choirs at age ten, and gospel music has had a profound effect in shaping his approach to both vocals and piano. That influence is apparent on the poignant original What Is a Home Without a Mother? His grandfather was the R&B great James “Sugar Boy” Crawford (of Jock-A-Mo fame), and the grandson gives up his props on two of his grandfather’s collaborations with Dave Bartholomew—the gospel-flavored instrumental Morning Star and the mournful blues ballad You Gave Me Love. He knows how to dig into the blues as evidenced by his reworking of Jimmy Rogers’ Walkin’ By Myself. Crawford takes things all the way back to the roots of the city’s piano tradition with a laid-back ride through Jelly Roll Morton’s Buddy Bolden’s Blues.

The program deftly blends Crawford originals, like the Bolden-sounding Teana Titty and barrelhouse blues Baby Please Be True, with New Orleans piano warhorses, like Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor, Percy Mayfield’s Please Send Me Someone to Love and Jimmy Cox’s Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out. The lone track where Crawford gets some help is a reworking of the Nellie Lutcher hit Fine Brown Frame, which features a rollicking, fun-filled duet with classic Louisiana soul blues diva Carol Fran. Davell Crawford has played a lot of different music over the past three decades, and with Piano in the Vaults, Vol. 1 he reveals himself as a genuine New Orleans music master.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

FABULOUS THUNDERBIRDS

FABULOUS THUNDERBIRDS

Strong Like That

Severn Records – CD0067

The Fabulous Thunderbirds rose to fame as one of the founders of the mid-1970s blues rival scene in Austin, Texas, on the power of irrepressible vocalist/harmonica master Kim Wilson and the always right on time playing of guitarist Jimmie Vaughan.

On the band’s 13th studio album, Strong Like That, they continue the evolution from raucous, guitar-driven, blues-soaked party hounds to a band that successfully melds blues, R&B and soul into a tight mix that still packs plenty of grit and hints at the T-Birds signature roadhouse blues inclinations.

Wilson long ago assumed the mantle as the band’s only remaining original member, with Vaughan having departed in 1990 to be followed by a succession of accomplished and occasionally sensational guitarists and backing musicians that allow Wilson to explore his dual fascination with the blues and soul genres.

Strong Like That is stocked with songs that allow Wilson to explore the inner crooner that has coexisted with his bawdy cousin going back to such chestnuts as Full Time Lover from the band’s 1979 debut The Fabulous Thunderbirds.

While Johnny Moeller (guitar), Kevin Anker (keyboards) and Steve Gomes (bass) are holdovers from the band’s previous album, 2013’s On the Verge, drummer Robb Stupka joins the current Thunderbirds lineup. Album guests include Austin guitarist Anson Funderburgh, a frequent Wilson collaborator.

The album kicks off with a cover of the Temptations classic (I Know) I’m Losing You, which gets a funky treatment thanks to a propulsive groove laid down by guest drummer Wes Watkins and Gomes and bolstered by sizzling steel guitar work by guest Roosevelt Collier.

The Al Jackson–penned Drowning on Dry Land gets a lift from great horn section accents. Meet Me on the Corner is propelled by Gomes’ sweetly serpentine bassline and is one of two songs on the album written by Wilson. The title track, written by Gomes, closes the album on an upbeat, defiant note and is driven by Wilson’s assured vocals—“They can’t drag me down / because I’m strong like that”—Little Walter–inflected harp, a tasty keyboard riff and mellow horns.

—Rod Evans

DAVE BROMBERG BLUES BAND

DAVE BROMBERG BLUES BAND

The Blues, The Whole Blues and Nothing But the Blues

Red House Records – RHRCD 297

The Blues, The Whole Blues and Nothing But the Blues is compelling testimony to David Bromberg’s mastery of American roots music. For this fourth CD since his 2007 return from a 17-year recording hiatus, Bromberg teams with producer Larry Campbell for a second straight outing to deliver a recording that encompasses a broad spectrum of blues styles drawn from sources such as Robert Johnson, Bessie Smith, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Sonny Boy Williamson II, George “Little Hat” Jones, Muddy Waters and Ray Charles. Although Bromberg’s command of a multiplicity of string instruments has taken him far and wide stylistically through various genres that today have found a home under the Americana umbrella, he is deeply rooted in the blues, having been a guitar student of the Rev. Gary Davis in the 1960s.

Bromberg receives stellar support from his regular band—guitarist Mark Cosgrove, bassist Butch Amiot, drummer Josh Kanusky and fiddler Nate Grower—augmented by keyboardist Bill Payne, Campbell on guitar and as horn arranger, and on one track, a vocal chorus. Campbell has emerged from his collaborations with the late Levon Helm as a premier roots music producer, and once again the sound on this recording is clear, resonant and alive. There has always been a kind of self-deprecatory, tongue-in-cheek humor to Bromberg’s vocals, and that is still the case here as he interjects spoken monologues and asides into the performances.

Over the years, Bromberg has been largely cast as a folky, acoustic player, yet on the lion’s share of these tracks he plays electric guitar. The program kicks off with a searing slide intro and a muscular two-guitar attack on Johnson’s Walkin’ Blues. The Elmore James–inspired original You Don’t Have to Go features more blistering slide work that duels with Grower’s soaring fiddle. Bromberg serves up two rousing, horn-driven numbers: the rocking Why Are People Like That?, a Bobby Charles tune written for The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album and Bland’s Yield Not to Temptation, which finds him sparring with a vocal chorus. Williamson’s Eyesight to the Blind is transformed into a swinging romp with lively solos from Grower on fiddle and Payne on organ. Perhaps the standout of the electric guitar outings is the traditional country tune 900 Miles, which Campbell and Bromberg recast as a Howlin’ Wolf–inspired, crunching blues rocker that rides on a seductive guitar riff that instantly brings Hubert Sumlin to mind and features a devastatingly wicked slide solo. On the acoustic side of things, Bromberg delivers a tour de force solo rendition of Ray Charles’ A Fool for You, magically evoking the maestro’s piano with his flawless picking. Another acoustic standout finds Bromberg revisiting Delia from his first album in telepathic duet between his fingerpicking work and Campbell’s slide guitar. The verdict on The Blues, The Whole Blues and Nothing But the Blues is that David Bromberg has drawn upon decades of listening to and performing the blues to craft a flawlessly played and entertaining survey of the variations and possibilities within this still vibrant and adaptable source point for American music.

— Robert H. Cataliotti

VARIOUS ARTISTS

VARIOUS ARTISTS

The Musical Mojo of Dr. John: Celebrating Mac and His Music

Concord Records CRE00216

Ten years after launching his career on the late 1950s New Orleans R&B studio scene, Mac Rebennack transmogrified into Dr. John the Night Tripper, and his keyboard and guitar playing, vocals, songwriting and production work over the subsequent five decades have elevated him to legendary status in the realms of blues, jazz, R&B, funk and rock ’n’ roll. Rebennack certainly deserves the recognition that is signaled by The Musical Mojo of Dr. John: Celebrating Mac and His Music, an all-star tribute recorded at the Saenger Theatre in New Orleans during Jazz Fest week in 2014.

Rebennack’s “musical mojo” is rooted in a blues-tempered sensibility, committed to the deep funk and percolating rhythms of his hometown, and infused with a darkly mysterious spirituality. There is something unique about him, an ineffable quality that ultimately does not come across throughout this two-disc set. Musical director Don Was assembled a first-rate house band composed of New Orleans (guitarist Brian Stoltz and keyboardist John Gros) and non-New Orleans (keyboardist Chuck Leavell and drummer Kenny Aronoff) musicians, and the big surging blues-tinged rock and R&B-flavored sound they achieve is well played, energized and highly polished, but not loose, funky and shadowy, like the doctor when his mojo is working.

One factor that may account for the lack of a distinctive Dr. John flavor is that only ten of the 22 tracks are original Rebennack compositions. While many of the cover tunes have been recorded and played regularly by him over the years, these performances are just not imbued with the man’s trademark mojo. Irma Thomas’ singing remains one of the wonders of the R&B world, and she delivers a knockout version of Buddy Johnson’s Since I Fell for You, but it does not evoke a connection to the honoree. The case is similar with performances like Jason Isbell’s take on Huey Smith’s Blow Wind Blow or the Radiatorsʼ Dave Maloneʼs hip cover of Lead Belly’s Goodnight Irene or Ryan Bingham’s revival of Bill Quateman’s Back By the River.

There are some tracks where the song choices are puzzling, like Shannon McNally doing Bobby Charles’ Street People because he was a buddy of Rebennack or John Fogerty tearing it up on the monster groove of Gary U.S. Bonds’ hit New Orleans, seemingly because of the locale it celebrates. Rebennack’s deep catalog is packed with so many underrated tunes, so when artists unearth these gems and apply their distinct talents and recast them, the mojo starts working, like Widespread Panic and the Dirty Dozen joining forces for a sprawling Familiar Reality or Warren Haynes’ devastating slide attack on You Lie. Another surprise is that, aside from Big Chief Monk Boudreaux’s expectedly solid rendition of Earl King’s Big Chief, there is no overt nod to Professor Longhair, the seminal source point for Rebennack’s mojo. This also points to a lost opportunity; rather than have the late Allen Toussaint run through his own Life, two grand pianos could have been set side by side to let Toussaint and Rebennack work out on some Tipitina variations.

Assembling this much talent to extol the wonders of Dr. John assuredly resulted in some genuine fireworks, including Mavis Staples sparring with the brass band polyphony on Lay My Burden Down; the unprocessed second line funk of drummer Zigaboo Modeliste and bassist George Porter on Junko Partner; the punchy swing of Let’s Make a Better World by John Boutté and Cyril Neville engaged in a passionate call-and-response with the McCrary Sisters on Indian Red. Ultimately, it is the man himself who truly shines here. Rebennack appears on five tracks, and four of them (even Mac cannot make Bruce Springsteen funky on Right Place Wrong Time) testify to the fact that Dr. John’s mojo is still working, including a stellar piano/vocal/saxophone trio version of Please Send Me Someone to Love with Rebennack, Aaron Neville and Charles Neville; trumpeter Terence Blanchard providing the perfect complement to the poignant vocal on Rain and extended full-band treatments of I Walk on Guilded Splinters and Such a Night.

—Robert H. Cataliotti

RORY BLOCK

RORY BLOCK

Hard Luck Child: A Tribute to Skip James

Stony Plain – SPCD 1373

Hard Luck Child: A Tribute to Skip James is the fifth CD in singer/guitarist Rory Block’s “Mentor Series,” musical paeans to the blues masters she met and learned from as a teenaged guitarist in the 1960s: Son House, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Rev. Gary Davis, Mississippi John Hurt and now, Skip James. Each of these men was a blues visionary with a uniquely definitive approach to the idiom, and James could be the most challenging subject in the group not only because of his idiosyncratic guitar stylings and hauntingly plaintive vocals but because he also boasted an inimitable approach to the piano.

Block opens the program with Nehemiah James, her original biographical homage to James that explores the secular/scared duality of his art while riding a resonant slide riff and a hip little percussion groove. She then works her way through nine classic tracks from the James repertoire, including Special Rider Blues, Cypress Grove Blues, Devil Got My Woman and Hard Time Killing Floor Blues. Block has been playing and singing the blues for five decades, so she applies her own style to the material, rather than trying to pull off likely doomed-to-failure imitations. While James’ guitar work featured an intricate fingerpicking style, Block integrates her signature slide work into this approach. For her adaptions of two songs that James performed on piano, If You Haven’t Any Hay, Get on Down the Road and Little Cow and Calf Is Gonna Die Blues, Block plays in a slinky, slide style that imbues the tracks with a bouncy swing. When she explores the sacred side of James’ musical impulses, she creates a gospel feel by including a multi-tracked vocal chorus on Jesus Is a Mighty Good Leader and I’m So Glad.

Hard Luck Child: A Tribute to Skip James closes with the title track, which Block delivers with a sure handed confidence and a passionate resonance that bears witness to the existential insight of the man who crossed paths with a 15-year-old girl all those years ago. She clearly took the music and life lessons he imparted to heart, and this celebration of a mentor is filled with music that is both historical and vital.

— Robert H. Cataliotti

![4 Pnl 1 Tray CD Dgpk [Converted].New 8-26-09](https://livingblues.com/wp-content/uploads/MitchKashmar_WestCoastToast-300x268.jpg) MITCH KASHMAR

MITCH KASHMAR

West Coast Toast

Delta Groove Music – DGPCD174

West Coast Toast is a salute to the West Coast blues harmonica tradition that was fostered when George “Harmonica” Smith settled in Los Angeles in the mid-1950s, eventually inspiring young local players like Rod Piazza, William Clarke and Kim Wilson. Mitch Kashmar emerged from the next generation of players in this style that essentially melds postwar Chicago blues with jump blues and swing grooves. His first studio session in ten years, this recording reveals a soulful singer and a harmonica man with impressive chops. Ultimately, what makes West Coast Toast so effective and enthralling is the super tight band Kashmar has assembled, including Junior Watson on guitar, Bill Stuve on upright bass, Fred Kaplan on piano/organ and Marty Dodson on drums. They work together like a well-oiled machine to deliver a hard-driving, stripped-down sound on a program that mixes Kashmar’s original tunes and blues classics.

The opener, East of 82nd Street, epitomizes the West Coast style, a swinging jump blues instrumental featuring bebop-inspired harp/guitar unison lines and Watson’s staccato guitar fills. That bop influence, particularly a classic like Horace Silver’s Doodlin’, seems to be the inspiration for the loping groove and signature riff on Kashmar’s Canoodlin’, an almost eight-minute instrumental that gives plenty of room for the harmonica, guitar and organ to stretch out. Evidence of Silver’s influence also shows up in both Kaplan’s piano work and the Latin-tinged groove on a reworking of Willie Dixon’s Too Many Cooks.

Kashmar’s harmonica is definitely at the center of things, and he really cuts loose on the rocking shuffle The Petroleum Blues. More outstanding guitar/harmonica interplay distinguishes Billy Boy Arnold’s Don’t Stay Out All Night. Makin’ Bacon (possibly referencing Bacon Fat, the landmark late 1960s/early 1970s band that featured both Smith and Piazza on harmonica) is a funky, soulful instrumental that allows Kashmar to strut his stuff. Kashmar shows off his versatility as he blows unamplified harp in the pre-war Chicago style on John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson’s Alcohol Blues, which also features some rocking dialogue between Kaplan’s piano and Watson’s guitar. Mitch Kashmar proves himself a powerful ambassador of an under-recognized school of blues harmonica; hopefully, it will not take another ten years to follow up West Coast Toast.

— Robert H. Cataliotti

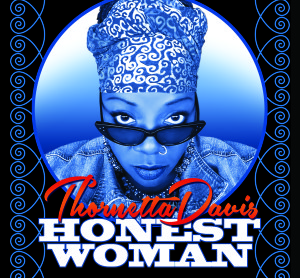

THORNETTA DAVIS

THORNETTA DAVIS

Honest Woman

Sweet Mama Music – No #

“Well-kept secret” has become a blues cliché, but it’s hard to avoid when discussing Detroit’s Thornetta Davis. Her 1990 recording debut featured her fronting a Detroit-based soul band called the Chisel Brothers; five years later, she cut an EP with the funk-metal band Big Chief, who also accompanied her on Sunday Morning Music, her first recording under her own name (one song from that album, Cry, was used in an episode of The Sopranos). Since then, despite a few high profile out-of-town engagements such as the 2000 VH1/Vogue Fashion Awards, she has seemed mostly content to remain in Detroit, cultivating an avid local following and dropping tantalizing hints of an ongoing recording project that even some of her staunchest admirers questioned whether it would come to fruition. (A 2000 live CD, recorded at Detroit’s Music Menu, only whetted their appetite for a full set of new material.).

Now, after 20 years, she has made good on her promise. Longtime Davis watchers won’t be surprised at this set’s eclecticism. That Don’t Appease Me spikes the well-known You Don’t Love Me / Wang Dang Doodle riff with rock-like force, even as Davis’ vocal delivery keeps it resolutely blues-focused; Set Me Free alternates between atmospheric neo-gospel and mid-range funk as Davis sings her story of a spiritual seeker vacillating between desperation and faith. I Believe (Everything Gonna Be Alright) references one of Muddy Waters’ trademark vocal routines before tearing into a hard-chugging, slide-driven, roadhouse-rocking boogie. Get Up and Dance Away Your Blues and Can We Do It Again invoke the jazzy élan of Detroit’s Hastings Street heyday; the title track sounds crafted to break into the southern soul market; Feels Like Religion is a soul-stirring celebration of life. An array of special guests, including guitarist Larry McCray and harpist Kim Wilson, widen the palette even further.

Through it all, Davis conveys intense emotion without overkill, relying instead on her gifts for timbre, tone and texture, even at her most unfettered; and the soul-bearing honesty that powers both her songwriting and her singing makes itself evident throughout. Dare we hope that the Blues Diva of Detroit has finally decided to unfurl her wings and ascend to her rightful place in the modern day blues firmament?

—David Whiteis